The teen sitting across from me avoided making eye contact as he responded to my questions. He provided thoughtful answers in a soft voice as he looked down at the rubber band in his hands, stretching and turning it repeatedly. Clearly this young man was struggling with symptoms of depression such that he was disengaged from his friends, skipping track practices, missing homework assignments, sleeping too much. Yet when I asked him if I could share his symptoms with his guidance counselor so that he could get some support in school, he quickly replied, “No,” saying that he didn’t want anyone at school to know. “I’m only telling you about this, “ he insisted, “because I’ll never see you again.”

The teen sitting across from me avoided making eye contact as he responded to my questions. He provided thoughtful answers in a soft voice as he looked down at the rubber band in his hands, stretching and turning it repeatedly. Clearly this young man was struggling with symptoms of depression such that he was disengaged from his friends, skipping track practices, missing homework assignments, sleeping too much. Yet when I asked him if I could share his symptoms with his guidance counselor so that he could get some support in school, he quickly replied, “No,” saying that he didn’t want anyone at school to know. “I’m only telling you about this, “ he insisted, “because I’ll never see you again.”

My colleagues and I routinely hear such statements from the adolescents we screen for depression and suicidal thoughts. Although these teens readily reveal their symptoms and struggles to us, adults who enter their middle and high schools for a few weeks each year and then leave as quickly as we arrive, they are reluctant to reveal their inner thoughts and feelings to the people they see every day: parents, teachers, school counselors. And the parents of these teens repeatedly tell us that they do not want us to share the results of our screening efforts with school personnel who could provide support during the school day. Consistent with our experiences in schools, research suggests that, even when adults in school are educated about the signs and symptoms of youth depression and are prepared to support teens who are struggling, such gatekeeper education programs often do not increase the likelihood that teens, who, for example, are experiencing suicidal thoughts, will seek out adults for support. Moreover, one study revealed that most teens who have made a suicide attempt said they would not share this fact with a counselor or other adult at school, and that they believed their parents would not want them to do so.

How significant of a problem is depression and suicidal behavior among adolescents? A recent Pew Research Center poll indicates that adolescents view depression and anxiety as key concerns for themselves and their peers, and as even more significant concerns than drug/alcohol abuse and bullying. We know that rates of depression in youth are quite high, with as many as 11% experiencing a Major Depressive Disorder by the end of adolescence. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among those ages 10-19, and depression is common among adolescents who exhibit suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In fact, suicidal thinking has been found to be elevated even among adolescents who experience symptoms of depression without meeting full diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder.

If the many adolescents who are struggling with mental health concerns are not willing to seek support from school personnel, where are they getting the information and support they need? How can we provide teens with tools to promote health and wellbeing?

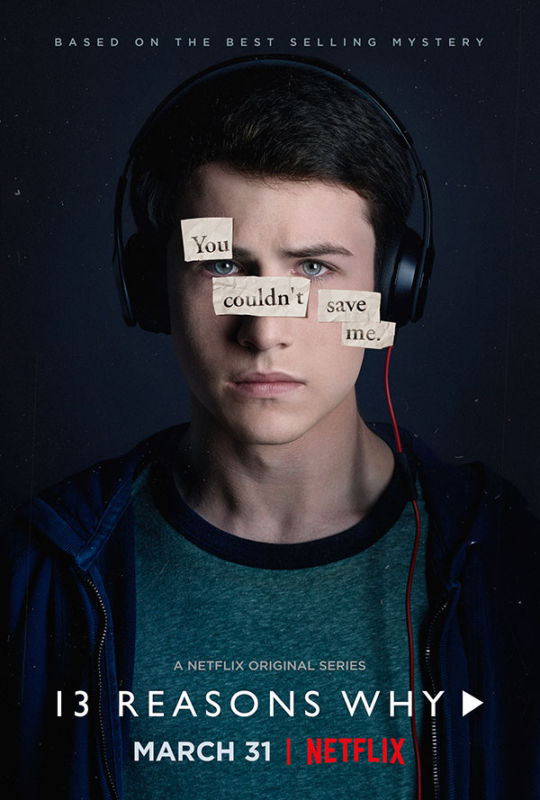

We know that teens are turning to sources outside of their homes and school communities for information about youth depression, and for indications of how best to manage strong feelings they may be experiencing. For example, a new study indicates that teens may be gathering information about managing suicidal thoughts from television programming, and we have long been warned about the effects of modeling on suicidal behavior among youth, leading to clusters of suicide in a community. In the context of so many unhealthy personal and media examples of teens managing depression, there is much we can do to support the teens in our lives, both those we know well and those we know less well.

In fact, warm interpersonal relationships, and the presence of a close relationship with an adult outside of the home, have been found to be significant sources of strength and to promote resilience in children at risk for depression. For example, in a study of children of depressed parents who maintain good mental health over time, high-quality social relationships were identified as a protective factor. More specifically, researchers in Ireland found that, in a study of risk and protective factors for depression and anxiety in a community sample of adolescents, the presence of “one good adult” in a teen’s life was identified as a protective factor.

You can serve as that “one good adult” and influence adolescents you know toward health and wellbeing: your own children, your children’s friends, and the children of your friends. You can provide a safe source of support to teens in your community, and you can contribute toward reducing the stigma associated with depression, anxiety, and other forms of mental illness. How can you do this? Talk directly to the teens you encounter, and express interest in them, their relationships, and their activities. Talk to the teens you are shuttling to practice in the back of your car, and listen carefully to their conversations. Ask teens how they are feeling, and what they think about, and what they worry about. Listen to their responses, and express caring and concern. Reinforce the value of mental health treatment, and reinforce the value of parents, school counselors, and others in the community who can provide mental health supports. Don’t be afraid to ask teens who report feelings of hopelessness or depression if they ever experience suicidal thoughts—asking this question will not encourage suicidal behavior. Share concerns with parents and others who are directly involved in an at-risk teen’s daily care. Support your children in establishing meaningful relationships with neighbors, an aunt or uncle, and encourage your children to share their feelings openly.

In this month of May, Mental Health Awareness Month, we have the opportunity to be intentional in our support of the adolescents we encounter in our communities, and to recognize the power we have to support their healthy growth and development.

Tracy Gladstone, Ph.D., is an associate director and senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women as well as the inaugural director of the Robert S. and Grace W. Stone Primary Prevention Initiatives, which aims to research, develop, and evaluate programs to prevent the onset of depression and other mental health concerns in children and adolescents. She is also an assistant in psychology at Boston Children’s Hospital, an instructor at Harvard Medical School, and a research scientist at Judge Baker Children’s Center. Gladstone leads depression prevention programs in two greater Boston school districts, to identify and connect adolescents to appropriate services who report depressive symptoms, self-injury, and suicidal thinking.

Abrutyn, S. & Mueller, A.S. (2014). Are suicidal behaviors contagious in adolescence? Using longitudinal data to examine suicide suggestion. American Sociological Review, 79, 211-227.

Avenevoli, S., Swendsen, J., He, J.P., Burstein, M., & Merikangas, K.R. (2015). Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 37-44.

Balazs, J., Miklosi, M., Kereszteny, A., Hoven, C.W., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Apter, A.,…Wasserman, D. (2013). Adolescent subthreshold-depression and anxiety: psychopathology, functional impairment and increased suicide risk. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 670-677.

Beardslee, W.R. & Podorefsky, D. (1988). Resilient adolescents whose parents have serious affective and other psychiatric disorders: Importance of self-understanding and relationships. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 63-69.

Bridge, J.A., Greenhouse, J.B., Ruch, D., Stevens, J., Ackerman, J., Shefftall, A.H., Horowitz, L.M.,…Campo, J.V. (in press). Association between the release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and suicide rates in the United States: An interrupted time series analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Collishaw, S., Hammerton, G., Mahedy, L., Sellers, R., Owen, M.J., Craddock, N., Thapar, A.K.,…Thapar, A. (2016). Mental health resilience in the adolescent offspring of parents with depression: A prospective longitudinal study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3, 49-57.

Dazzi, T., Gribble, R., Wessely, S., & Fear, N.T. (2014). Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychological Medicine, 44, 3361-3363.

Dooley, B., Fitzgerald, A., & Mac Giollabhui, N. (2015). The risk and protective factors associated with depression and anxiety in a national sample of Irish adolescents. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32, 93-105.

Insel, B.J. & Gould, M.S. (2008). Impact of modeling on adolescent suicidal behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31, 293-316.

Nock, M.K., Green, J.G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K.A., Sampson, N.A., Zaslavsky, A.M., & Kessler, R.C. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 300-310.

Silk, J.S., Vanderbilt-Adriance, E., Shaw, D.S., Forbes, E.E, Whalen, D.J., Ryan, N.D. & Dahl, R.E. (2007). Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological contexts. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 841-865.

Whitney, S.D. Renner, L.M., Pate, C.M., & Jacobs, K.A. (2011). Principals’ perceptions of benefits and barriers to school-based suicide prevention programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 869-877.

Wyman, P.A., Brown, C.H., Inman, J., Cross, W., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Guo, J., & Pena, J.B. (2008). Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 104-115.

Close to half a century has passed since I lived in

Close to half a century has passed since I lived in  But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return.

But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return. ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.”

ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.” A spectacular

A spectacular  all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied.

all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied. Recently I returned from Liberia, which USA Today just rated as

Recently I returned from Liberia, which USA Today just rated as  Another view—one that I would like to align with the research and action of the Wellesley Centers for Women—is one that sees (and contributes to) hope, promise, and enthusiasm in and with regard to African youth and their prospects. An approach that asks African youth for their own perspectives and aspirations, one that embraces African youth and their insights and talents, and one that takes the historical, political, economic, structural, and systemic context of African youths’ lives into consideration—and, at times, challenges those—is the one I would like not only to endorse, but to operationalize. It is an approach that sees the wealth in people, not just one that sees the poverty created by their circumstances. It is also an approach that cultivates African youth leadership.

Another view—one that I would like to align with the research and action of the Wellesley Centers for Women—is one that sees (and contributes to) hope, promise, and enthusiasm in and with regard to African youth and their prospects. An approach that asks African youth for their own perspectives and aspirations, one that embraces African youth and their insights and talents, and one that takes the historical, political, economic, structural, and systemic context of African youths’ lives into consideration—and, at times, challenges those—is the one I would like not only to endorse, but to operationalize. It is an approach that sees the wealth in people, not just one that sees the poverty created by their circumstances. It is also an approach that cultivates African youth leadership. Why Racialized Exclusion Hurts and How We Can Remain Resilient

Why Racialized Exclusion Hurts and How We Can Remain Resilient No one looks for a job in a newspaper’s “Help Wanted” section anymore. But some 50 years after the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commissions in 1968 said that listing jobs under “male” and “female” headings was illegal, the psychological divide lingers – in sports.

No one looks for a job in a newspaper’s “Help Wanted” section anymore. But some 50 years after the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commissions in 1968 said that listing jobs under “male” and “female” headings was illegal, the psychological divide lingers – in sports. , Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the

, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the  Today, it is almost impossible not to talk about immigration and what that represents to every single individual in our nation. As an immigrant transgender woman who was granted

Today, it is almost impossible not to talk about immigration and what that represents to every single individual in our nation. As an immigrant transgender woman who was granted  In January 2018, President Trump famously raised his concerns regarding the “lack of Norwegians” and the excess of immigrants from low-income countries entering the United States – and

In January 2018, President Trump famously raised his concerns regarding the “lack of Norwegians” and the excess of immigrants from low-income countries entering the United States – and  Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1967, famously characterized the human mind as a storehouse filled with two kinds of seeds: good and bad. Humans have the capacity to be both good and evil, he pointed out, and it’s the seeds we water that ultimately grow. Think about that. When we look around the world today, we see a lot of evil sprouting up all around, and we wonder where it came from. We scratch our heads, we point fingers, and sometimes, in frustration, we join in the fray. Based on Thich Nhat Hanh’s insight, we should really take a closer look at how we are watering the seeds of the very evils we decry and detest – incivility, hate-based conflict and violence, and even basic intolerance.

Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1967, famously characterized the human mind as a storehouse filled with two kinds of seeds: good and bad. Humans have the capacity to be both good and evil, he pointed out, and it’s the seeds we water that ultimately grow. Think about that. When we look around the world today, we see a lot of evil sprouting up all around, and we wonder where it came from. We scratch our heads, we point fingers, and sometimes, in frustration, we join in the fray. Based on Thich Nhat Hanh’s insight, we should really take a closer look at how we are watering the seeds of the very evils we decry and detest – incivility, hate-based conflict and violence, and even basic intolerance. About twenty years ago, I received some unbearable news about a dear friend. A highly intelligent, strong, and beautiful woman of African-descent revealed to me that she contracted HIV as a result of having unprotected sex with a man who had the virus. Twenty years ago, I was convinced that the virus was an automatic death sentence for my friend. Thankfully, with advances in medical technology, not only is she still with us but she is healthy and thriving. However, keep in mind that she has the necessary resources that are needed in order to take care of herself, so she can successfully manage her overall health. She is middle class, has a good health insurance plan, has access to the appropriate health care, and has a supportive social network that encourages her to maintain her health.

About twenty years ago, I received some unbearable news about a dear friend. A highly intelligent, strong, and beautiful woman of African-descent revealed to me that she contracted HIV as a result of having unprotected sex with a man who had the virus. Twenty years ago, I was convinced that the virus was an automatic death sentence for my friend. Thankfully, with advances in medical technology, not only is she still with us but she is healthy and thriving. However, keep in mind that she has the necessary resources that are needed in order to take care of herself, so she can successfully manage her overall health. She is middle class, has a good health insurance plan, has access to the appropriate health care, and has a supportive social network that encourages her to maintain her health. Ph.D., is a former post-doctoral intern at the

Ph.D., is a former post-doctoral intern at the  “Someday you will go to college, too,” a young mother tells her eight year old son at her baccalaureate graduation ceremony.

“Someday you will go to college, too,” a young mother tells her eight year old son at her baccalaureate graduation ceremony.  I spend a lot of time thinking and talking about our research on sexual violence case attrition and why most rape cases

I spend a lot of time thinking and talking about our research on sexual violence case attrition and why most rape cases  In the “

In the “

This landscape is familiar, strewn with ash and blood. We’ve been here before, too often, seeking the living, counting our dead. I know the terrain, can pick my way stumbling over the bodies, the stench of fear and hatred lingering in the air; the thoughts and prayers; the headlines and statistics.

This landscape is familiar, strewn with ash and blood. We’ve been here before, too often, seeking the living, counting our dead. I know the terrain, can pick my way stumbling over the bodies, the stench of fear and hatred lingering in the air; the thoughts and prayers; the headlines and statistics. At the Wellesley Centers for Women, we envision a world of justice, peace, and wellbeing for women and girls, children and youth, families and communities, in all their diversity around the world. Like so many, our will and spirits have been tested by recent events, but our resolve has been strengthened. The fatal shooting of two African Americans in a Jeffersontown, Kentucky, grocery store; the more than a dozen pipe bombs sent to CNN and prominent progressive political leaders and supporters across the country; and the mass shooting of eleven worshippers at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, are evidence that we need to stand strong and work together—to provide comfort, hope, knowledge, and power — to help shape a better world. We at WCW stand with those whose lives are forever changed. Only when social equity and equality, psychological wellbeing, peace, and freedom from violence and want evince for all people will our work have reached its true aim.

At the Wellesley Centers for Women, we envision a world of justice, peace, and wellbeing for women and girls, children and youth, families and communities, in all their diversity around the world. Like so many, our will and spirits have been tested by recent events, but our resolve has been strengthened. The fatal shooting of two African Americans in a Jeffersontown, Kentucky, grocery store; the more than a dozen pipe bombs sent to CNN and prominent progressive political leaders and supporters across the country; and the mass shooting of eleven worshippers at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, are evidence that we need to stand strong and work together—to provide comfort, hope, knowledge, and power — to help shape a better world. We at WCW stand with those whose lives are forever changed. Only when social equity and equality, psychological wellbeing, peace, and freedom from violence and want evince for all people will our work have reached its true aim. The sexual assault allegations leveled by psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford against U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh have consumed the country. The events as described by Ford are not an anomaly for U.S. teens. As researchers, we know that there is a high prevalence of sexual assault among teens today and that schools are not implementing effective strategies to address this kind of violence. But the data haven't always been available—it is only in about the last two decades that we can reliably measure the prevalence of sexual assault among teens.

The sexual assault allegations leveled by psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford against U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh have consumed the country. The events as described by Ford are not an anomaly for U.S. teens. As researchers, we know that there is a high prevalence of sexual assault among teens today and that schools are not implementing effective strategies to address this kind of violence. But the data haven't always been available—it is only in about the last two decades that we can reliably measure the prevalence of sexual assault among teens. Nan Stein

Nan Stein This week, the

This week, the  Emily Style’s beautiful phrase “curriculum as window and mirror” has had an enormous impact on my work as a teacher and teacher educator over the last 30 years. Other proponents of multicultural education have, over those years, deployed many more words to assert what curriculum ought to be and do. Emily’s lyrical imagery is testament to her skills as both poet and educational theorist. And, generations of teachers are all the better for having taken these words to heart as they consider the choices they make in responding to the students in their classrooms.

Emily Style’s beautiful phrase “curriculum as window and mirror” has had an enormous impact on my work as a teacher and teacher educator over the last 30 years. Other proponents of multicultural education have, over those years, deployed many more words to assert what curriculum ought to be and do. Emily’s lyrical imagery is testament to her skills as both poet and educational theorist. And, generations of teachers are all the better for having taken these words to heart as they consider the choices they make in responding to the students in their classrooms. When I first came across

When I first came across  This article was posted by Amy Banks, M.D., on September 18, 2018 in her Wired for Love blog on Psychology Today.

This article was posted by Amy Banks, M.D., on September 18, 2018 in her Wired for Love blog on Psychology Today. About 20 tweens pile into the unassuming studio space of their ballet school in mid-July. There are no frills here. The waiting area is small and a bit disheveled; the cinder block building has seen its share of life. But look closer: there’s magic inside.

About 20 tweens pile into the unassuming studio space of their ballet school in mid-July. There are no frills here. The waiting area is small and a bit disheveled; the cinder block building has seen its share of life. But look closer: there’s magic inside.

As a country we seem to be moving far away from the nurturing and sustaining activity of the settlement houses of our past. The first settlement house, established in New York City’s Lower East Side – Neighborhood Guild – was founded by Stanton Coit, and just a few years later came Hull House in Chicago, materializing through the passionate vision of Jane Addams. Settlement houses were the cornerstone of communities as they over time took on the task of educating citizens, providing English language classes for immigrants, organizing employment connections, and offering enrichment and recreation opportunities to all in the neighborhood. A most significant beginning to the current child and youth development field, settlement houses provided childcare services for the children of working mothers. The Immigrants’ Protective League, The Juvenile Protective Association, The Institute for Juvenile Research, The Federal Children’s Bureau, along with Child Labor Laws can all trace back to the persistent national

As a country we seem to be moving far away from the nurturing and sustaining activity of the settlement houses of our past. The first settlement house, established in New York City’s Lower East Side – Neighborhood Guild – was founded by Stanton Coit, and just a few years later came Hull House in Chicago, materializing through the passionate vision of Jane Addams. Settlement houses were the cornerstone of communities as they over time took on the task of educating citizens, providing English language classes for immigrants, organizing employment connections, and offering enrichment and recreation opportunities to all in the neighborhood. A most significant beginning to the current child and youth development field, settlement houses provided childcare services for the children of working mothers. The Immigrants’ Protective League, The Juvenile Protective Association, The Institute for Juvenile Research, The Federal Children’s Bureau, along with Child Labor Laws can all trace back to the persistent national  This article was posted by Amy Banks, M.D., on June 19, 2018 in her Wired for Love blog on Psychology Today.

This article was posted by Amy Banks, M.D., on June 19, 2018 in her Wired for Love blog on Psychology Today. We don’t live in an “either/or” world. Most non-sport institutions get this. It’s why Starbucks has unisex bathrooms, why there are forms to change your gender on government documents, why there is even a concept of “preferred pronouns.”

We don’t live in an “either/or” world. Most non-sport institutions get this. It’s why Starbucks has unisex bathrooms, why there are forms to change your gender on government documents, why there is even a concept of “preferred pronouns.” Indian sprinter

Indian sprinter  The Wellesley Centers for Women is mourning the death of Deborah Holmes, Chair of the WCW Council of Advisors and a passionate activist committed to the lives of women, people of color, equity, and social justice across the world.

The Wellesley Centers for Women is mourning the death of Deborah Holmes, Chair of the WCW Council of Advisors and a passionate activist committed to the lives of women, people of color, equity, and social justice across the world. A few days ago, my eyes fell upon an online post discussing recent

A few days ago, my eyes fell upon an online post discussing recent  Even in this 21st Century, we have not yet come to accept that parenting is a shared component of our human condition. Every industry employs parents who are trying to balance their work obligations with their family roles. In fact, even non-parents can be called into a caregiving role, for example when their ageing parents need help. Gone are the days when a two-parent family could live on a single paycheck and when family roles were clearly divided. Therefore all of us, across gender and age, would benefit from a variety of workplace supports that accommodate our multiple roles as modern human beings.

Even in this 21st Century, we have not yet come to accept that parenting is a shared component of our human condition. Every industry employs parents who are trying to balance their work obligations with their family roles. In fact, even non-parents can be called into a caregiving role, for example when their ageing parents need help. Gone are the days when a two-parent family could live on a single paycheck and when family roles were clearly divided. Therefore all of us, across gender and age, would benefit from a variety of workplace supports that accommodate our multiple roles as modern human beings. A message from

A message from  with their own trauma history can be triggered by another traumatic event, even if it did not directly happen to them. In addition to the positive, supportive classroom climate and the social and emotional learning tools that Open Circle provides, some students may need additional time with a school psychologist or guidance counselor to help them manage their fears.

with their own trauma history can be triggered by another traumatic event, even if it did not directly happen to them. In addition to the positive, supportive classroom climate and the social and emotional learning tools that Open Circle provides, some students may need additional time with a school psychologist or guidance counselor to help them manage their fears. As I reflected earlier this month on

As I reflected earlier this month on  But the very fact that we can clearly delineate “black sports” and “white sports” is not an accident but something nurtured and presumed. If sports are more than athletic contests—if they have social, economic, and political value—we must care who gets to play.

But the very fact that we can clearly delineate “black sports” and “white sports” is not an accident but something nurtured and presumed. If sports are more than athletic contests—if they have social, economic, and political value—we must care who gets to play. As the 62nd Session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) at the United Nations in New York draws near, women from every corner of the world will convene to deliberate on the theme of CSW 2018: Challenges and Opportunities in achieving gender equality and the empowerment of rural women and girls. This year, the theme of empowerment has added significance. The #MeToo movement has shocked our collective conscience and made it impossible to ignore that empowerment goes far beyond economic agency.

As the 62nd Session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) at the United Nations in New York draws near, women from every corner of the world will convene to deliberate on the theme of CSW 2018: Challenges and Opportunities in achieving gender equality and the empowerment of rural women and girls. This year, the theme of empowerment has added significance. The #MeToo movement has shocked our collective conscience and made it impossible to ignore that empowerment goes far beyond economic agency. Several countries, notably Japan, have put forward “win-win” economic policies, but they ignore controversial and difficult social policies such as violence against women. This approach is similar to the nations that peddled the “Asian Values” theory in the 1990s. The better approach is to reveal the interconnectedness of women’s economic participation with equal protection of laws.

Several countries, notably Japan, have put forward “win-win” economic policies, but they ignore controversial and difficult social policies such as violence against women. This approach is similar to the nations that peddled the “Asian Values” theory in the 1990s. The better approach is to reveal the interconnectedness of women’s economic participation with equal protection of laws. The fifth-grader’s voice was full of emotion as he shouted, “That’s not fair! What a mean thing to do!”

The fifth-grader’s voice was full of emotion as he shouted, “That’s not fair! What a mean thing to do!” By the end of my first year at Wellesley College, I knew that I wanted to explore the world of research. I had taken the first of many gender studies courses to come, and left class with a head full of questions that I not only wanted answers to, but wanted to take a stake at answering. A stroke of luck brought me to an event for students to meet with research scientists at the Wellesley Center for Women. A stroke of better luck brought me to Dr.

By the end of my first year at Wellesley College, I knew that I wanted to explore the world of research. I had taken the first of many gender studies courses to come, and left class with a head full of questions that I not only wanted answers to, but wanted to take a stake at answering. A stroke of luck brought me to an event for students to meet with research scientists at the Wellesley Center for Women. A stroke of better luck brought me to Dr.  The power of representation became personal when I began to cultivate a mentor-mentee relationship with Linda. Our weekly/bi-weekly research check-ins were not only crucial for the advancement of the qualitative research we were conducting and my own research skills, but also for developing my own sense of worth and potential. Little by little, I was able to learn about Linda’s life and experiences, research and otherwise. I found out she was Thai (like me)! I found out that she also struggled in her undergraduate years (who knew that researchers were not perfect?). She spoke about her queerness in ways that normalized my own burgeoning questions about sexuality and gender. She validated my questions, hopes, and fears no matter how naive, incomplete, or overwhelming. I was learning so much from someone who shared my most salient identities - - from a successful academic whose work brimmed with passion. If she could do it, maybe I could too.

The power of representation became personal when I began to cultivate a mentor-mentee relationship with Linda. Our weekly/bi-weekly research check-ins were not only crucial for the advancement of the qualitative research we were conducting and my own research skills, but also for developing my own sense of worth and potential. Little by little, I was able to learn about Linda’s life and experiences, research and otherwise. I found out she was Thai (like me)! I found out that she also struggled in her undergraduate years (who knew that researchers were not perfect?). She spoke about her queerness in ways that normalized my own burgeoning questions about sexuality and gender. She validated my questions, hopes, and fears no matter how naive, incomplete, or overwhelming. I was learning so much from someone who shared my most salient identities - - from a successful academic whose work brimmed with passion. If she could do it, maybe I could too. For those too busy to watch the five-minute video, here is a summary of the study. The researchers brought three individuals to the social science lab and told one of them that they were in charge—essentially giving that person power over the other two. While the group was busy with the assigned task of writing boring university policy, the researchers brought out a plate of four cookies. Initially, each of the three participants ate one cookie each, leaving one on the plate. Interestingly, most of the time, the person given the power eventually ate the fourth cookie. In Dr. Keltner's study taking the fourth cookie correlated with having power and also with a decrease in activity of the mirror neuron system (the circuits in your brain that produce empathy and allow appreciation of the impact of your actions on others). Further, as the researchers watched the behavior of those given power, they observed that the people in charge ate differently. They chewed with their mouths open and occasionally had little pieces of food dropping out of their mouths. Dr. Keltner describes this change in the level of interpersonal awareness as the "paradox of power"—the qualities that often bring someone to power, like empathy and the ability to listen to others, diminish once a person is in power.

For those too busy to watch the five-minute video, here is a summary of the study. The researchers brought three individuals to the social science lab and told one of them that they were in charge—essentially giving that person power over the other two. While the group was busy with the assigned task of writing boring university policy, the researchers brought out a plate of four cookies. Initially, each of the three participants ate one cookie each, leaving one on the plate. Interestingly, most of the time, the person given the power eventually ate the fourth cookie. In Dr. Keltner's study taking the fourth cookie correlated with having power and also with a decrease in activity of the mirror neuron system (the circuits in your brain that produce empathy and allow appreciation of the impact of your actions on others). Further, as the researchers watched the behavior of those given power, they observed that the people in charge ate differently. They chewed with their mouths open and occasionally had little pieces of food dropping out of their mouths. Dr. Keltner describes this change in the level of interpersonal awareness as the "paradox of power"—the qualities that often bring someone to power, like empathy and the ability to listen to others, diminish once a person is in power. As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives.

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives. I have been a fan of

I have been a fan of  With our cell phones actively participating in locating the office, along with the skills of our car service driver, we arrived after lunch on November 14, 2017. About 12 women artisans were gathered together along with some staff -- they greeted us with a special handmade mandala on the floor, and after a candle lighting ceremony, they sang us a song that they had written.

With our cell phones actively participating in locating the office, along with the skills of our car service driver, we arrived after lunch on November 14, 2017. About 12 women artisans were gathered together along with some staff -- they greeted us with a special handmade mandala on the floor, and after a candle lighting ceremony, they sang us a song that they had written.

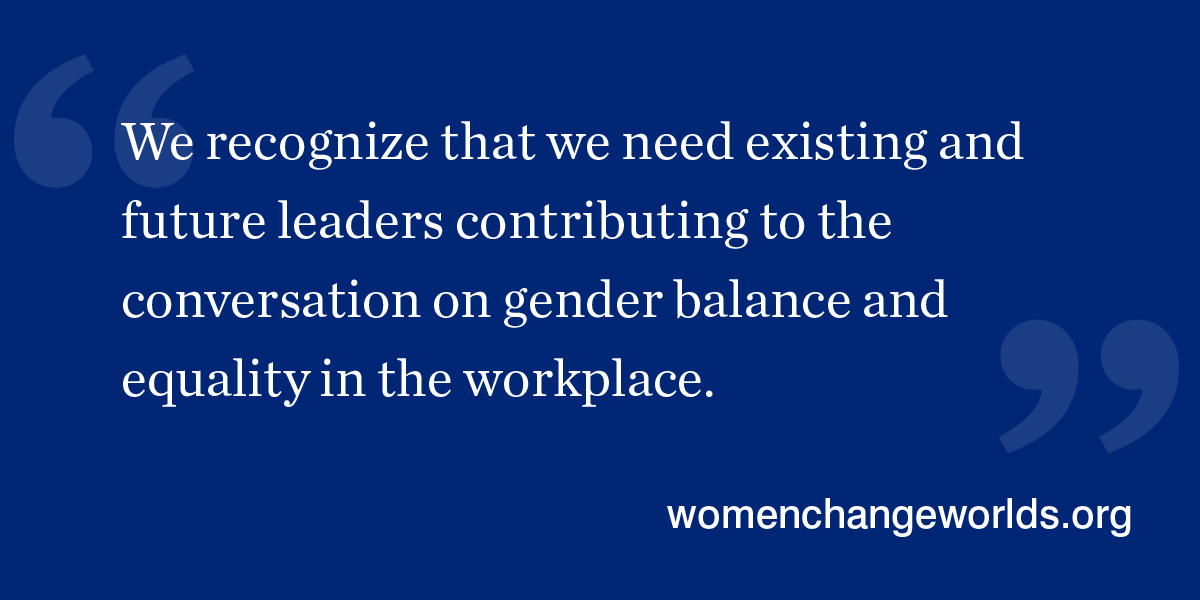

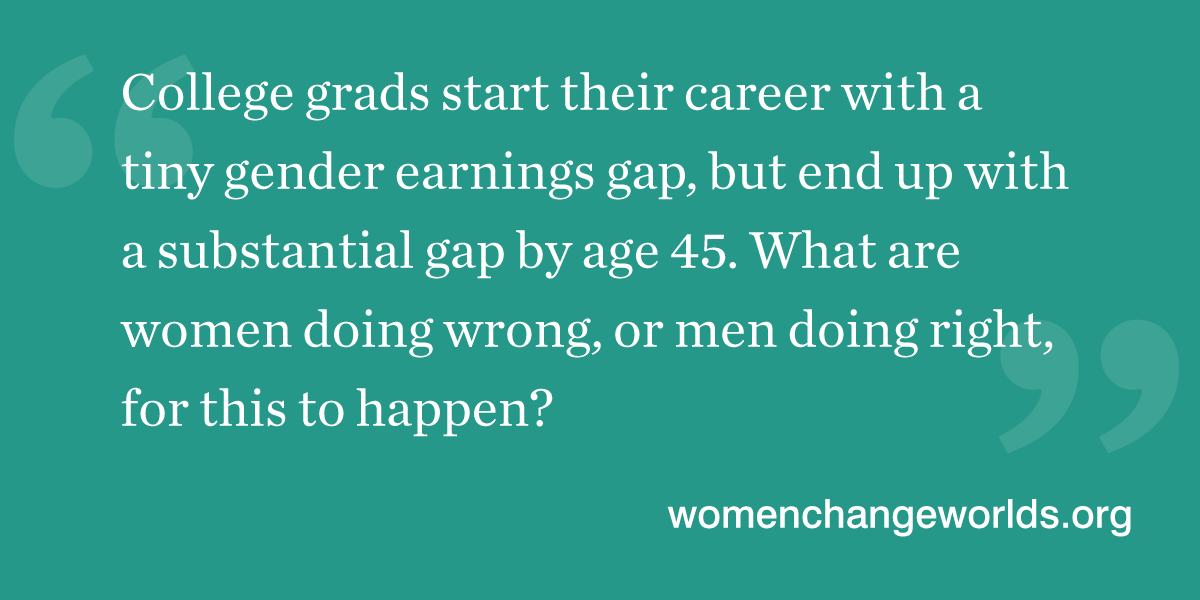

We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many

We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many  Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to

Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to  In a meeting with the Congressional Black Caucus earlier in October, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer,

In a meeting with the Congressional Black Caucus earlier in October, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer,  My colleagues Vicki Kramer, Allison Konrad, and I interviewed 50 women directors, 12 CEOs (nine male), and seven corporate secretaries at Fortune 1000 companies. We found that

My colleagues Vicki Kramer, Allison Konrad, and I interviewed 50 women directors, 12 CEOs (nine male), and seven corporate secretaries at Fortune 1000 companies. We found that  I applaud the strength and solidarity of the women (and men, too) who are asserting with the hashtag

I applaud the strength and solidarity of the women (and men, too) who are asserting with the hashtag  We must remember it is not only Hollywood producers who sexually assault and not only young actors who are the victims. The rapists and perpetrators of sexual assault include:

We must remember it is not only Hollywood producers who sexually assault and not only young actors who are the victims. The rapists and perpetrators of sexual assault include: The Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India  It is common knowledge that there is a link between lower levels of education and early marriage. The

It is common knowledge that there is a link between lower levels of education and early marriage. The  Nandita Dutta is deputy manager at the

Nandita Dutta is deputy manager at the  Since 1981, the United Nations has observed International Day of Peace on September 21. In its resolution, the UN marked the day as a “

Since 1981, the United Nations has observed International Day of Peace on September 21. In its resolution, the UN marked the day as a “ WILPF has been one of many women’s peace organizations who successfully lobbied the UN Security Council to recognize, in Resolution 1325 (

WILPF has been one of many women’s peace organizations who successfully lobbied the UN Security Council to recognize, in Resolution 1325 ( It’s back-to-school time and families, youth, and educators must adjust their schedules for another school year. In the midst of the forms and information families receive – or that get “lost” in a child’s backpack or locker – you may have heard something about a

It’s back-to-school time and families, youth, and educators must adjust their schedules for another school year. In the midst of the forms and information families receive – or that get “lost” in a child’s backpack or locker – you may have heard something about a  From my desk at NIOST, I’m starting the school year by working at the national, state, and local levels to support educators and administrators in their efforts to promote positive youth outcomes, especially in the expanding field of SEL. Specifically, I am researching the SEL programs that states are currently adopting in preparation for our forthcoming workshop for out-of-school time (OST) leaders on how to integrate these practices into school-age child care or other OST settings. As I do this work, my background as a former school committee member and education advocate means I can’t resist passing along the newest SEL information that comes across my desk to the regional school administrators in my community who are convening the SEL planning discussions for local schools.

From my desk at NIOST, I’m starting the school year by working at the national, state, and local levels to support educators and administrators in their efforts to promote positive youth outcomes, especially in the expanding field of SEL. Specifically, I am researching the SEL programs that states are currently adopting in preparation for our forthcoming workshop for out-of-school time (OST) leaders on how to integrate these practices into school-age child care or other OST settings. As I do this work, my background as a former school committee member and education advocate means I can’t resist passing along the newest SEL information that comes across my desk to the regional school administrators in my community who are convening the SEL planning discussions for local schools. Friday, September 8, is

Friday, September 8, is  and sharing books begins at birth. Try to read aloud to your baby every day! With the very young infant you may look at only one page of a book- in time, you can look together at two or more. Turning the pages, labeling pictures and describing what is happening on the page all lead to vocabulary and grammar development. Reading to your baby also predicts their early reading and writing skills! Cuddling together to read and share books is a very pleasant experience for both the infant and you! These very early enjoyable experiences can lead to a life-long love of reading. When there are plenty of books available, an infant may even try to look at the pictures in books on her/his own. And, remember your local library is a good source of books for your infant.

and sharing books begins at birth. Try to read aloud to your baby every day! With the very young infant you may look at only one page of a book- in time, you can look together at two or more. Turning the pages, labeling pictures and describing what is happening on the page all lead to vocabulary and grammar development. Reading to your baby also predicts their early reading and writing skills! Cuddling together to read and share books is a very pleasant experience for both the infant and you! These very early enjoyable experiences can lead to a life-long love of reading. When there are plenty of books available, an infant may even try to look at the pictures in books on her/his own. And, remember your local library is a good source of books for your infant.

How did this turnaround happen? I’m glad of it, but I don’t know. Some of the people I talked to theorized about a better-educated population, a two-term black president, more understanding and acceptance of LGBTQ people and other nonmainstream folk—and even the experience of the 1970s, from which at least some white people in Boston concluded that the anger, fear, and hatred that they directed toward people of color caused only misery and destruction—not only to others but even to themselves.

How did this turnaround happen? I’m glad of it, but I don’t know. Some of the people I talked to theorized about a better-educated population, a two-term black president, more understanding and acceptance of LGBTQ people and other nonmainstream folk—and even the experience of the 1970s, from which at least some white people in Boston concluded that the anger, fear, and hatred that they directed toward people of color caused only misery and destruction—not only to others but even to themselves.

As a developmental psychologist who works from an

As a developmental psychologist who works from an

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior. It’s

It’s

Victims of Domestic Violence Often Face Housing Problems

Victims of Domestic Violence Often Face Housing Problems

Mentorship was the reason I came to Wellesley College, all the way across the globe from Sri Lanka. Back in 2013 on the day of the United Nations’

Mentorship was the reason I came to Wellesley College, all the way across the globe from Sri Lanka. Back in 2013 on the day of the United Nations’