Digital communication systems, such as social media platforms, are created for the masses but aren’t often designed for a large scope of their user base: adolescent girls from marginalized communities. The Youth, Media & Wellbeing (YMW) Research Lab, in collaboration with the Computer Science Department at Wellesley College, holds an annual summer workshop for adolescent girls to explore STEM learning spaces and become designers and creators of their own digital communication systems. (This year’s workshop ran July 11-15.)

As research interns from different educational backgrounds, we all contributed our unique expertise to last year’s summer digital wellbeing workshop. We were mentored by Dr. Linda Charmaraman, director of the YMW Research Lab, and Dr. Catherine Delcourt, assistant professor of computer science at Wellesley, to explore research on human-computer interaction (HCI), specifically on participatory design and positive social media use with middle school girls. At the end of an exciting and fast-paced summer, we published and presented our work—titled “Innovating Novel Online Social Spaces with Diverse Middle School Girls: Ideation and Collaboration in a Synchronous Virtual Design Workshop”—at CHI 2022, an international HCI conference.

The aim of this participatory design workshop was to engage middle school girls in social media innovation, digital wellbeing, positive social media use, STEM identity exploration, collaboration, and computational design. Conducted virtually over four days, students were divided into small groups of three or four, grouped by age, with an assigned facilitator.

The idea generation and collaboration sessions were very fun to be involved with, especially as we watched students envision unique positive spaces online. Their ideas included an application that uses a robot to monitor and filter out negative messages, a music-based application to spread kindness, and a simulation game to develop interests and explore career paths for teenagers. Students also showed a great interest in climate change activism, spreading positivity, finding friends and peers from their neighborhood, and building a large community of like-minded individuals. They often took initiative during this time to develop prototypes and sketches.

Overall, we noted how important it was to maintain a positive and uplifting environment for the students in the workshop, which through our experience, allowed everyone to feel more comfortable with one another and share personal anecdotes with the group. We observed individual trajectories of growth through the four-day workshop and were keen on exploring our findings regarding intentional collaboration and facilitation with underrepresented middle school girls.

As research interns, we gained a lot of insight and experience being involved in the workshop, from curriculum development to report writing to the conference presentation.

It was also an interesting experience for us, as researchers and facilitators, as we became the workshop participants’ peers and mentors during the process. Stepping out of the research mindset we had while preparing the curriculum for the workshop, we were doing virtual field work by interacting with the adolescents to understand their conception and opinions of social media and STEM. This process allowed us to get to know the participants personally and join their efforts to co-design a novel and positive social online space.

To discuss our experience with the workshop and the process of publishing our paper about it, we presented at the Tanner Conference at Wellesley College and the hybrid CHI 2022 conference, during which we presented our research to HCI experts.

We were so honored to be part of such a great team and are excited to see the impactful results of this workshop in the coming summers. As research interns, we gained a lot of insight and experience being involved in the workshop, from curriculum development to report writing to the conference presentation. We all continue to engage in the research and provide input on the upcoming summer workshop through the YMW Youth Advisory Board, which allows us to test-drive activities with past workshop participants and facilitators aged 12-23. This summer, Dr. Delcourt is working with Connie to develop a facilitator training based on last year’s experience and previous research. Being involved with this workshop has helped us explore personal interests, given us the opportunity for new experiences, and taught us the tools of the trade about the research process.

If it weren't for the cold email Sidrah sent to Dr. Charmaraman expressing interest in her lab or the internship applications Connie and Teresa submitted to be involved in the lab, we would have not had this opportunity. Lastly, we could not have had such a vibrant educational experience without Dr. Delcourt and Dr. Charmaraman’s continued support and mentorship, and we’re especially grateful to them for introducing us to HCI research from the perspective of social computing and developmental psychology. As aspiring researchers, we hope to continue working toward creating more inclusive spaces in technology for girls while also supporting their positive development and digital wellbeing.

Sidrah Durrani is a master’s student in developmental psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Connie Gu is a member of the Wellesley College Class of 2024 majoring in media arts and sciences.

Teresa Xiao is a Class of 2022 graduate of Wellesley College who majored in psychology.

I never knew that I would have the opportunity to do social science research as an undergraduate until I got to Wellesley College. Towards the end of my first year, with my academic interests starting to gravitate toward Sociology and South Asia Studies, I knew I wanted to connect the concepts I was learning in the classroom to action-oriented research that produced tangible results for communities that I cared about. Through the helpful guidance of my peers, professors, and mentors, I discovered that I could get that opportunity by working at the Wellesley Centers for Women.

I never knew that I would have the opportunity to do social science research as an undergraduate until I got to Wellesley College. Towards the end of my first year, with my academic interests starting to gravitate toward Sociology and South Asia Studies, I knew I wanted to connect the concepts I was learning in the classroom to action-oriented research that produced tangible results for communities that I cared about. Through the helpful guidance of my peers, professors, and mentors, I discovered that I could get that opportunity by working at the Wellesley Centers for Women. This

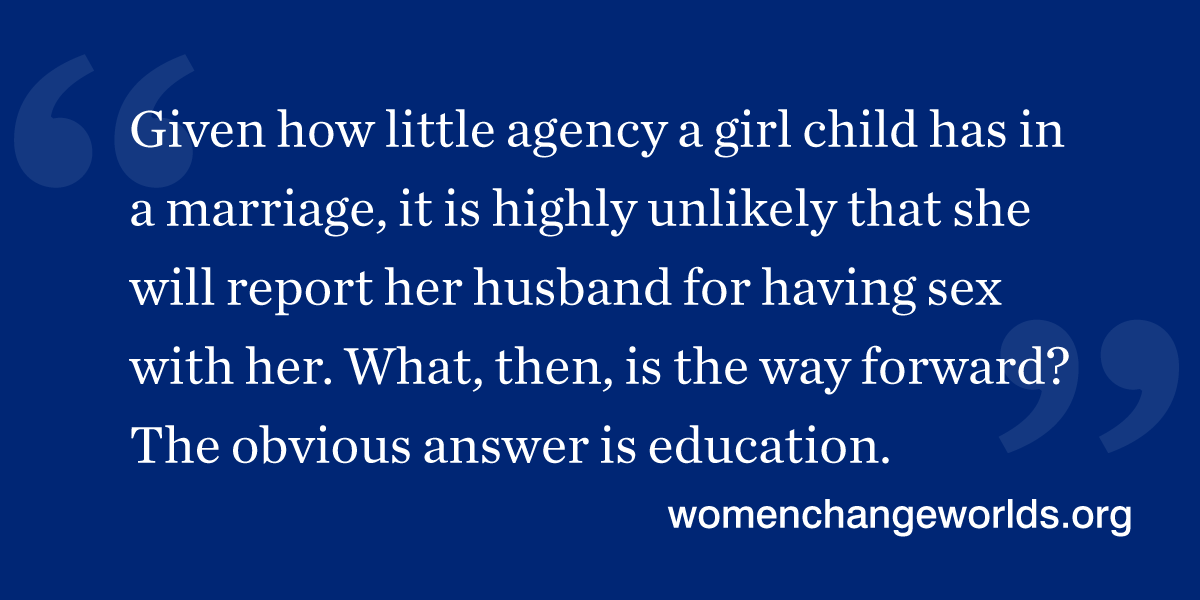

This  The Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India  It is common knowledge that there is a link between lower levels of education and early marriage. The

It is common knowledge that there is a link between lower levels of education and early marriage. The  Nandita Dutta is deputy manager at the

Nandita Dutta is deputy manager at the