In a meeting with the Congressional Black Caucus earlier in October, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer, Sheryl Sandberg, made a public commitment to appoint an African American to its currently all-white board of directors – in the foreseeable future.

In a meeting with the Congressional Black Caucus earlier in October, Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer, Sheryl Sandberg, made a public commitment to appoint an African American to its currently all-white board of directors – in the foreseeable future.

The promise came when members of the Congressional Black Caucus were questioning Sandberg about the lack of diversity on Facebook’s board and at all levels of employment at Facebook where only three percent of employees are African Americans, and there are no black executives. Lawmakers confronted Sandberg about Facebook advertising that has been linked to Russian accounts purchased during the 2016 election that were connected to Black Lives Matter. Members of the Congressional Black Caucus said that if more blacks were in decision making positions, the connection with Russian accounts and anti-Black Lives Matter content may have been caught before the FBI looked into the issue.

But is one African American board member going to be able to bring a loud enough voice to change the status quo on the board and also move the company toward greater diversity in its rank and file? Drawing on our research on how many women it takes to change corporate board dynamics we conclude that a lone member of an underrepresented group is unlikely to be an effective voice for change.

My colleagues Vicki Kramer, Allison Konrad, and I interviewed 50 women directors, 12 CEOs (nine male), and seven corporate secretaries at Fortune 1000 companies. We found that the benefits of having women on a corporate board are more likely to be realized when three or more women serve on a board.

My colleagues Vicki Kramer, Allison Konrad, and I interviewed 50 women directors, 12 CEOs (nine male), and seven corporate secretaries at Fortune 1000 companies. We found that the benefits of having women on a corporate board are more likely to be realized when three or more women serve on a board.

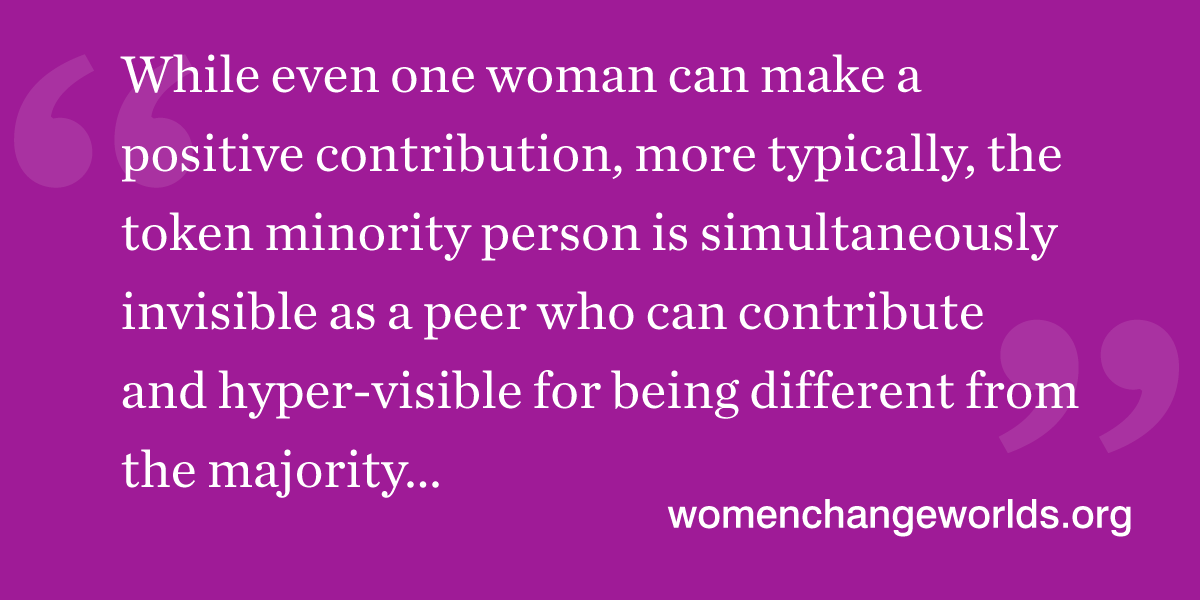

While even one woman can make a positive contribution, more typically, the token minority person is simultaneously invisible as a peer who can contribute and hyper-visible for being different from the majority, with irrelevant aspects of their demographic difference overshadowing their professional skills. We heard examples of lone women directors being talked over and otherwise ignored when they responded to a strategy question but asked about their preference for home decorating. In other words, being a token tends to be a powerless position.

Having two people different from the majority is generally an improvement over the token position. But it is corporations with three or more different people on their boards that tend to benefit the most from the diverse perspectives they can bring. Our results showed that with three or more women, board discussions expanded to include the interests of multiple stakeholders, including the community and to pursue answers to difficult questions such as CEO compensation and diversity. Three or more women were also able to change board dynamics toward a more collaborative approach to leadership, improving communication among directors and between the board and management.

Important to note is that Facebook’s board is currently comprised of eight individuals—six white men and two white women—and two of these individual are the inside directors, Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg. This elite structure reflects the lack of a wider perspective of viewpoints, experiences, concerns, priorities, and sensitivities. While this may have helped the organization’s growth, there are corporate responsibilities beyond the bottom line.

If Facebook is serious about its diversity problem, adding one African American to its board is not going to be enough. It takes a critical mass of three or more people who are different from the majority to bring about change on a board.

Sumru Erkut, Ph.D., is senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College. Her research interests include women’s leadership, racial/cultural norms and identity in youth and families, and adolescent development.

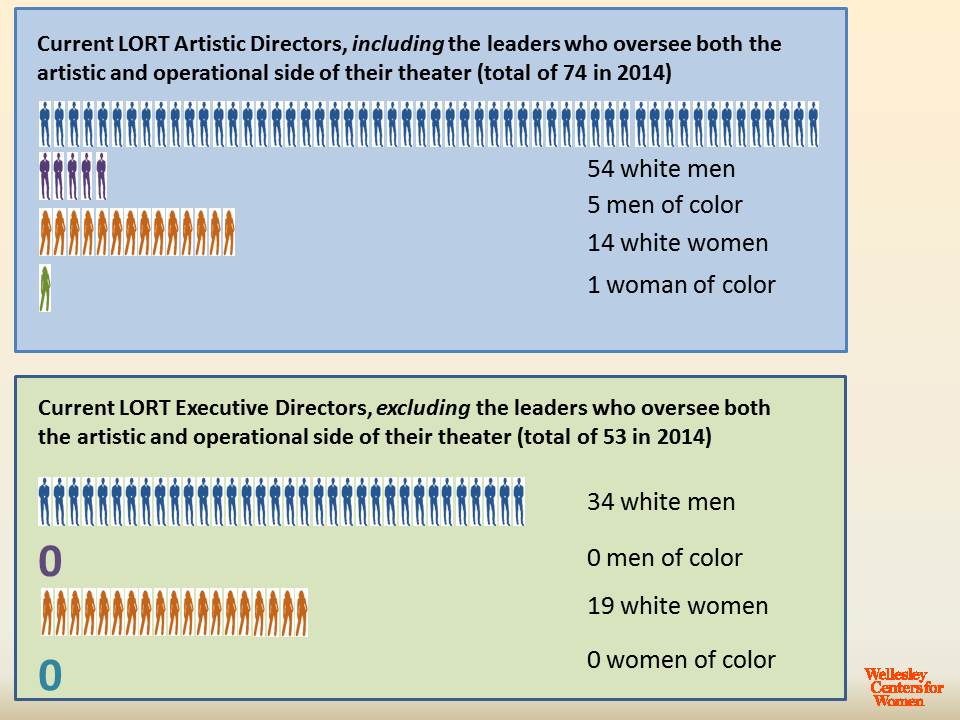

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs: But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career?

But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career?

members of Twitter’s board members have undergraduate degrees from liberal arts colleges: one has a degree in English; another in Asian Studies. Couldn’t female experts in entrepreneurial management, intellectual property law, investment management contribute, for example, contribute positively within such a governance structure? It was smart of Twitter to include diversity of educational and work experiences on its board. Twitter (and all corporations) needs to stop making excuses and go for greater diversity, by including female, minority, and international members on its board.

members of Twitter’s board members have undergraduate degrees from liberal arts colleges: one has a degree in English; another in Asian Studies. Couldn’t female experts in entrepreneurial management, intellectual property law, investment management contribute, for example, contribute positively within such a governance structure? It was smart of Twitter to include diversity of educational and work experiences on its board. Twitter (and all corporations) needs to stop making excuses and go for greater diversity, by including female, minority, and international members on its board.

My colleagues and I interviewed 50 same-sex couples in Massachusetts and their children. Some of the couples had chosen to get married and some had not. Whether or not a given couple chose to marry, they talked about the importance of the legitimacy and the recognition the change in the law offered them. Their sense was that when legal marriage is available to same-sex couples, the ramifications stretch far beyond the couples themselves. Perceptions of families, co-workers, neighbors, and strangers shift toward greater acceptance.

My colleagues and I interviewed 50 same-sex couples in Massachusetts and their children. Some of the couples had chosen to get married and some had not. Whether or not a given couple chose to marry, they talked about the importance of the legitimacy and the recognition the change in the law offered them. Their sense was that when legal marriage is available to same-sex couples, the ramifications stretch far beyond the couples themselves. Perceptions of families, co-workers, neighbors, and strangers shift toward greater acceptance.

by people who do not know the candidate personally. When there is no familiarity with the person being evaluated to trump the bias that makes men seem more competent, men are chosen over equally competent women.

by people who do not know the candidate personally. When there is no familiarity with the person being evaluated to trump the bias that makes men seem more competent, men are chosen over equally competent women.