Dear Friends of WCW:

Dear Friends of WCW:

Happy New Year! I hope that your winter break was restful and rejuvenating. With a wrap on 2023, we leap headlong into 2024 with a sense of renewal and openness to what lies ahead. Our 2023 Research & Action Report highlighted some of our accomplishments from the previous year, as well as some of the new projects we are just starting. From our work to evaluate Planned Parenthood’s new sex ed curriculum to a new study of what home-based child care providers need to survive, we are excited about what is on the horizon—including a project that’s particularly close to my heart.

At the end of this week, I’ll be traveling to Liberia to train student intern data collectors for the Higher Education for Conservation Activity (HECA), a program funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). My role on this project is Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Lead, and my work ensures that more women, youth, people with disabilities, and people from rural, forest-dependent communities can participate in higher education programs related to forestry, biodiversity, and conservation. Liberia contains the largest remnant of the disappearing Upper Guinean Rainforest, and we are trying to train more people to take care of it, for the benefit of all. It is important that women's unique experiences, perspectives, and ideas inform this effort, along with those of others who have been sidelined in the past. To be involved with an effort to stem climate change is new for WCW, and I'm excited that I can represent both WCW and the College on this larger team effort. Stay tuned for a travelogue on Women Change Worlds in February!

Like many of you, I am tuned in to the world around us, and watching closely what 2024 might bring. For one thing, this is a presidential election year, which could affect us profoundly by shaping the conditions of our work, including government funding streams. Secondly, there are still multiple wars going on in the world, and how we show up for peace and justice, whether individually or institutionally, as a women-led, social justice, research and action organization, will be important. What's more, climate change is likely to continue to affect the weather and a whole lot more, and how we weigh in on this consequential topic will be an area of emerging importance. Last but not least, artificial intelligence (AI) is the new kid on the block, and we are just beginning to understand what new issues it will raise, affecting gender equality, social justice, and human wellbeing as it evolves in ways we can scarcely imagine today. I’m sure you can think of many other things to add to this list. It is a time of converging grand challenges, but that has never scared WCW! We are on it!

As we begin this year, I am thankful for all of you and all you do to support WCW. However grand the challenges may be, it is always the small, local, everyday actions that give solutions life and make change sustainable. And it is also our interventions on the discourses of society—the ways in which we make sure WCW's research and action is heard and considered by wider audiences—that have the potential to change hearts and minds and structures of power in a positive, humane direction. Your material support of our work makes it sustainable and increases its power to influence change. In the famous words of an African philosopher, “I am because we are, and because we are, I am.” Thank you!

Happy 2024,

Layli

Layli Maparyan, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College.

This

This  Hospitals and universities are facing challenges that many have never seen before as they respond to COVID-19. Universities are

Hospitals and universities are facing challenges that many have never seen before as they respond to COVID-19. Universities are  A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.

A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.  As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

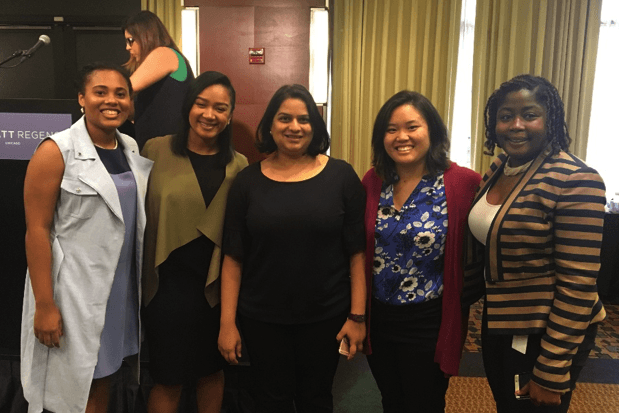

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives.

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives.

How did this turnaround happen? I’m glad of it, but I don’t know. Some of the people I talked to theorized about a better-educated population, a two-term black president, more understanding and acceptance of LGBTQ people and other nonmainstream folk—and even the experience of the 1970s, from which at least some white people in Boston concluded that the anger, fear, and hatred that they directed toward people of color caused only misery and destruction—not only to others but even to themselves.

How did this turnaround happen? I’m glad of it, but I don’t know. Some of the people I talked to theorized about a better-educated population, a two-term black president, more understanding and acceptance of LGBTQ people and other nonmainstream folk—and even the experience of the 1970s, from which at least some white people in Boston concluded that the anger, fear, and hatred that they directed toward people of color caused only misery and destruction—not only to others but even to themselves.

When the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced two years ago that it was planning to put a woman on the $10 bill, I voted for Harriet Tubman every chance I got. I was privileged to participate in an invitation-only phone call of women leaders with representatives from the Treasury Department, and I also voted online as an “ordinary citizen.” And I unapologetically urged my friends on social media to do the same. So, when the

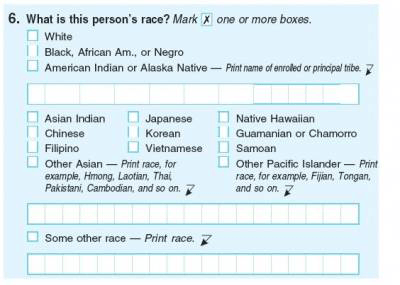

When the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced two years ago that it was planning to put a woman on the $10 bill, I voted for Harriet Tubman every chance I got. I was privileged to participate in an invitation-only phone call of women leaders with representatives from the Treasury Department, and I also voted online as an “ordinary citizen.” And I unapologetically urged my friends on social media to do the same. So, when the  Admittedly, if I had a private audience with Secretary Lew, I would suggest the inclusion of some notable Americans of Asian, Latin, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Pacific Islander descent in addition to the very welcome inclusion of African Americans on the new bills--and I might even suggest that he replace the image of slaveholder President Andrew Jackson (after whom my hometown, Jacksonville, Florida, is named, incidentally) with these diverse Americans, since he has (too) long had his day in the sun. I can only hope that this is the plan for the $50 and $100 bills!

Admittedly, if I had a private audience with Secretary Lew, I would suggest the inclusion of some notable Americans of Asian, Latin, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Pacific Islander descent in addition to the very welcome inclusion of African Americans on the new bills--and I might even suggest that he replace the image of slaveholder President Andrew Jackson (after whom my hometown, Jacksonville, Florida, is named, incidentally) with these diverse Americans, since he has (too) long had his day in the sun. I can only hope that this is the plan for the $50 and $100 bills!

My academic and teaching interests lie at the intersection of culture, computation, community, and cognition--I like to think about how technology can support learning in community and public settings. In my

My academic and teaching interests lie at the intersection of culture, computation, community, and cognition--I like to think about how technology can support learning in community and public settings. In my  Robbin Chapman

Robbin Chapman

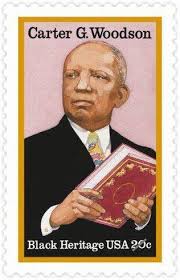

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School.

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School. women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African.

women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African. After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to

After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to  ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met. I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts.

I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts. This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the

This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

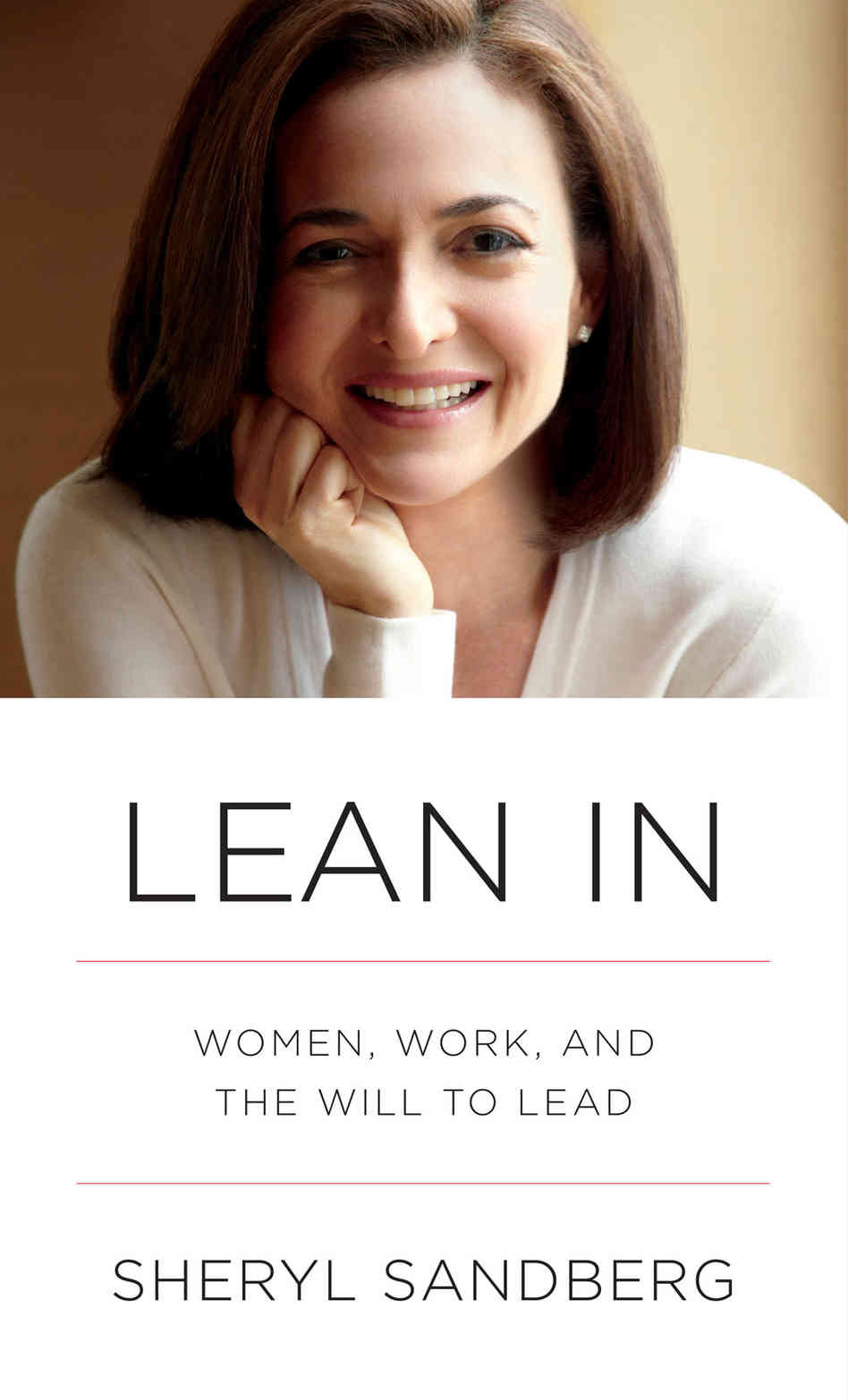

members of Twitter’s board members have undergraduate degrees from liberal arts colleges: one has a degree in English; another in Asian Studies. Couldn’t female experts in entrepreneurial management, intellectual property law, investment management contribute, for example, contribute positively within such a governance structure? It was smart of Twitter to include diversity of educational and work experiences on its board. Twitter (and all corporations) needs to stop making excuses and go for greater diversity, by including female, minority, and international members on its board.

members of Twitter’s board members have undergraduate degrees from liberal arts colleges: one has a degree in English; another in Asian Studies. Couldn’t female experts in entrepreneurial management, intellectual property law, investment management contribute, for example, contribute positively within such a governance structure? It was smart of Twitter to include diversity of educational and work experiences on its board. Twitter (and all corporations) needs to stop making excuses and go for greater diversity, by including female, minority, and international members on its board.

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

My colleagues and I interviewed 50 same-sex couples in Massachusetts and their children. Some of the couples had chosen to get married and some had not. Whether or not a given couple chose to marry, they talked about the importance of the legitimacy and the recognition the change in the law offered them. Their sense was that when legal marriage is available to same-sex couples, the ramifications stretch far beyond the couples themselves. Perceptions of families, co-workers, neighbors, and strangers shift toward greater acceptance.

My colleagues and I interviewed 50 same-sex couples in Massachusetts and their children. Some of the couples had chosen to get married and some had not. Whether or not a given couple chose to marry, they talked about the importance of the legitimacy and the recognition the change in the law offered them. Their sense was that when legal marriage is available to same-sex couples, the ramifications stretch far beyond the couples themselves. Perceptions of families, co-workers, neighbors, and strangers shift toward greater acceptance.

H.R.377) would strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

H.R.377) would strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

What are some cheap nutritious foods? In no particular order, the Biro family’s diet last week consisted of rice, beans, potatoes, inexpensive meat (specifically split chicken breasts on sale, and stew meat on sale), bananas, eggs, carrots (but you have to peel them yourself--having the factory do the work for you and turn them into baby carrots costs too much), pasta, homemade pancakes, nuts, oatmeal and super cheap granola bars we bought in bulk (more on this later). We bought a small crate of “Clementine” oranges on sale for $6, or $0.20 apiece. We made homemade pizza one night, with dough from scratch costing roughly $0.40, the sauce about $1 and mozzarella at $3, totaling not quite $5 for 2 pizzas, with leftovers for lunch. We did buy fresh broccoli, which is expensive at $0.30 per serving, so we didn’t have much. Frozen vegetables are usually cheaper, but not always. Lentils are cheap and high-quality calories but we didn’t get those in.

What are some cheap nutritious foods? In no particular order, the Biro family’s diet last week consisted of rice, beans, potatoes, inexpensive meat (specifically split chicken breasts on sale, and stew meat on sale), bananas, eggs, carrots (but you have to peel them yourself--having the factory do the work for you and turn them into baby carrots costs too much), pasta, homemade pancakes, nuts, oatmeal and super cheap granola bars we bought in bulk (more on this later). We bought a small crate of “Clementine” oranges on sale for $6, or $0.20 apiece. We made homemade pizza one night, with dough from scratch costing roughly $0.40, the sauce about $1 and mozzarella at $3, totaling not quite $5 for 2 pizzas, with leftovers for lunch. We did buy fresh broccoli, which is expensive at $0.30 per serving, so we didn’t have much. Frozen vegetables are usually cheaper, but not always. Lentils are cheap and high-quality calories but we didn’t get those in.

life-changing impact of our own

life-changing impact of our own

pragmatic level, it was pointed out that the statistical apparatus which will make disaggregation of data possible on global or country-level indicators remains to be designed or put into place.

pragmatic level, it was pointed out that the statistical apparatus which will make disaggregation of data possible on global or country-level indicators remains to be designed or put into place.

by people who do not know the candidate personally. When there is no familiarity with the person being evaluated to trump the bias that makes men seem more competent, men are chosen over equally competent women.

by people who do not know the candidate personally. When there is no familiarity with the person being evaluated to trump the bias that makes men seem more competent, men are chosen over equally competent women.

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although