Below is an excerpt by Nancy Peter, Ed.D., director of the McKinney Center for STEM Education at the Philadelphia Education Fund, from the book The Heartbeat of the Youth Development Field: Professional Journeys of Growth, Connection, and Transformation. The book was co-edited by NIOST Director Georgia Hall, Ph.D., Jan Gallagher, Ph.D., of Clear, Effective Communications, and NIOST Research Associate Elizabeth Starr, M.Ed. Here, Peter talks about the many pathways people take into youth work, and the need to support them with clear entry points, opportunities for advancement, fair compensation, and continuous professional development—no matter how they arrived in the field.

Youth workers are often described as “passionate.” They feel called to do the work, have a strong desire to serve or give back to their communities, and are committed to building positive relationships with youth. Most likely a conversation with a youth worker will quickly reveal their passion. This is corroborated by the research: surveys consistently show that this passion for the work is a strength of the field. The practitioner essays that make up this book give voice to this hard-to-describe quality—a passion, a calling, an artistry, the heart work. It is part of what makes this workforce unique. Moreover, it is part of what makes this workforce impactful. It is a true strength that can and should be articulated, celebrated, and leveraged. The aim of this book is to shine a spotlight on this strength.

This passion, though, is only one part of the picture of a strong workforce, and elevating it is only one part of our work as field-builders and leaders. It also needs to be supported. Critical foundational workforce supports—clear entry points, opportunities for advancement, fair compensation, and continuous professional development—are needed to sustain the energy and commitment the workforce brings.

Whichever pathway they take into the field, youth workers are similar to workers in any other field: they need to be supported with opportunities for professional growth and continual professional development

As the field struggles with recruitment, a longstanding issue exacerbated by the pandemic, we need to better understand the mechanisms by which people currently enter youth work. Like many of the youth practitioners in this chapter’s essays, I did not set out to become a youth work professional. In college, I majored in animal behavior because I loved animals. That love led me to volunteer at the local environmental education center—where I discovered a passion for education that has guided me ever since. I worked in environmental education, then in museum education, and then in a large city park. That’s when I realized I was also interested in work that affected people. I moved into children’s policy, out-of-school time programming, and positive youth development. Today, as director of the McKinney Center for STEM Education at the Philadelphia Education Fund, I no longer work directly with youth. Instead, I focus on professional development, curriculum development, and organizational capacity-building.

Whichever pathway they take into the field, youth workers are similar to workers in any other field: they need to be supported with opportunities for professional growth and continual professional development. A strong system is needed to provide this support, including the option of academic pathways, both access to credentials and higher education; career pathways tying experience, professional development, and formal education to advancement; and increases in compensation and benefits commensurate with experience and training.

Professional development is one specific workforce support that enables youth workers to develop their skills and knowledge and advance in the field. The practitioner authors in this book talk about their ongoing, meaningful professional development to scaffold growing competence and confidence, whether that means attending workshops and conferences, being mentored, or coached by a supervisor or colleague, participating in a peer learning community, or—for most—some combination of these.

In these essays, mid-career youth workers present their own compelling stories of their entries into the profession, their journeys up the career ladder, their successes, and the obstacles they have overcome. Several essayists emphasize how their own participation in youth programs influenced their eventual choice to work in such programs. Three of the five describe circuitous routes into the field. Only one entered college with the intention of getting a degree to support a career in youth work, though others mention college work along the way. For all five, their professional pathways took unanticipated twists and turns. Every one of them experienced on-the-job learning and professional development that ranged from formal opportunities to informal mentorships and coaching.

As a field, we must explore the ways in which career pathways are more available to some potential youth workers than to others. Then we can integrate ongoing research with our individual and collective stories to find ways to redress these fundamental inequities.

Nancy Peter, Ed.D., is the director of the McKinney Center for STEM Education at the Philadelphia Education Fund. The above excerpt appears in the book The Heartbeat of the Youth Development Field: Professional Journeys of Growth, Connection, and Transformation.

Nearly

Nearly

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist.

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist. Senior Research Scientist

Senior Research Scientist  May is Mental Health Awareness Month. This year, it comes at a time when we have an increased focus on mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Media reports have focused on the

May is Mental Health Awareness Month. This year, it comes at a time when we have an increased focus on mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Media reports have focused on the  April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking. On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

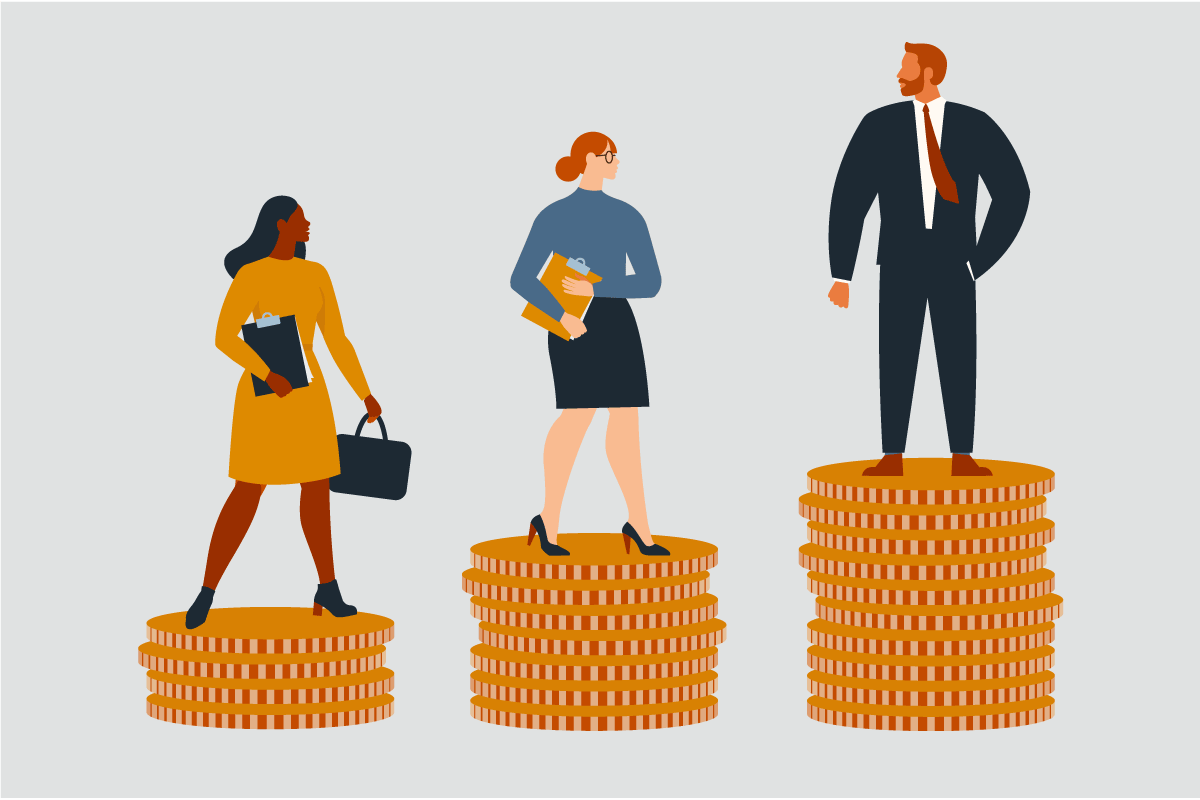

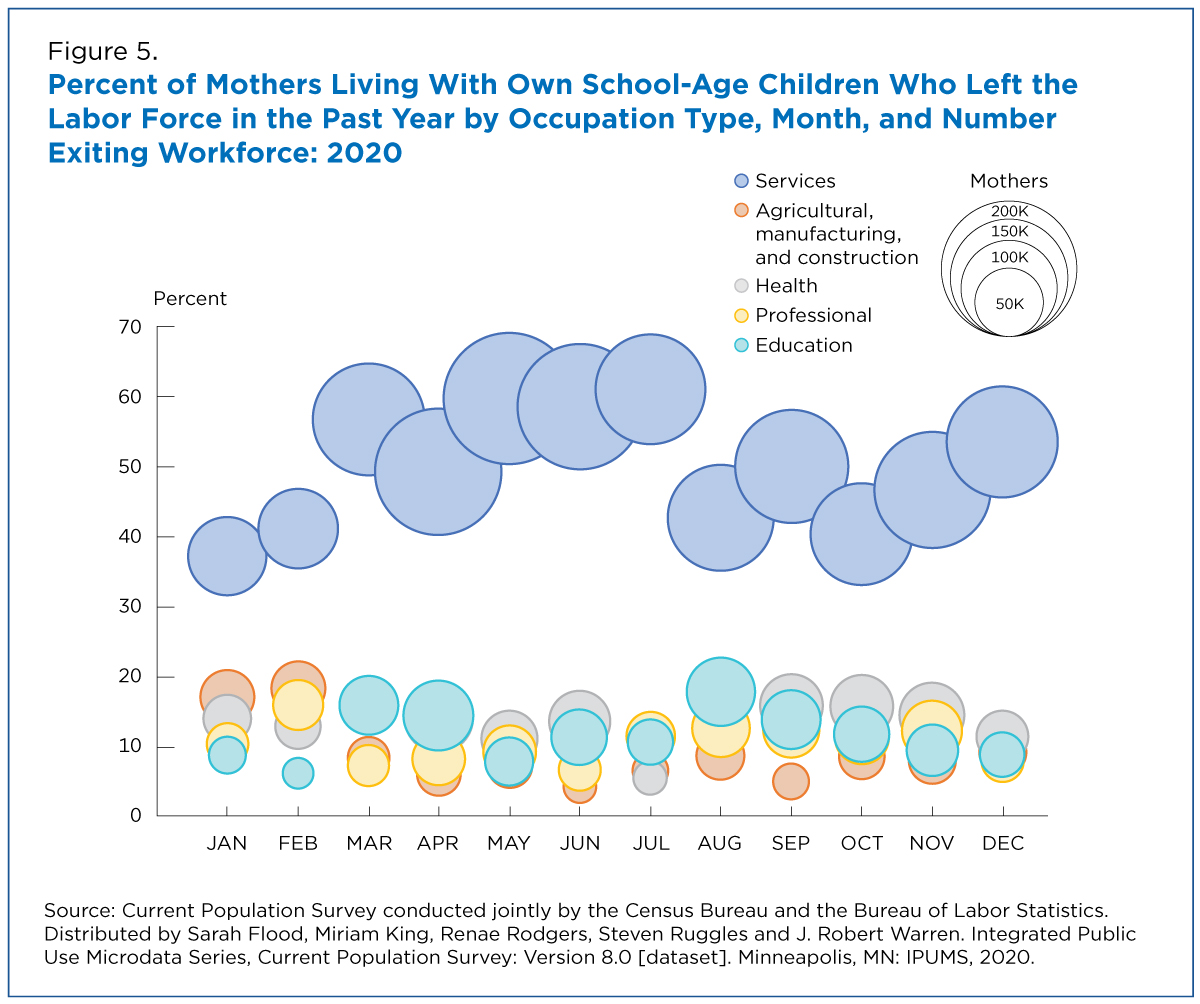

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

I spent the past semester working with Professor

I spent the past semester working with Professor  Today, the

Today, the  We at the Wellesley Centers for Women are starting our week with a sense of hope and possibility. We are proud to have a new

We at the Wellesley Centers for Women are starting our week with a sense of hope and possibility. We are proud to have a new  The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.

The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.  In my recently released book,

In my recently released book,  In 2018, I began a

In 2018, I began a

The callous killing of

The callous killing of  Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for

Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for  I never knew that I would have the opportunity to do social science research as an undergraduate until I got to Wellesley College. Towards the end of my first year, with my academic interests starting to gravitate toward Sociology and South Asia Studies, I knew I wanted to connect the concepts I was learning in the classroom to action-oriented research that produced tangible results for communities that I cared about. Through the helpful guidance of my peers, professors, and mentors, I discovered that I could get that opportunity by working at the Wellesley Centers for Women.

I never knew that I would have the opportunity to do social science research as an undergraduate until I got to Wellesley College. Towards the end of my first year, with my academic interests starting to gravitate toward Sociology and South Asia Studies, I knew I wanted to connect the concepts I was learning in the classroom to action-oriented research that produced tangible results for communities that I cared about. Through the helpful guidance of my peers, professors, and mentors, I discovered that I could get that opportunity by working at the Wellesley Centers for Women. The challenges of isolation and loneliness have become apparent over the past several months of social distancing. Not only are we physically separated from our friends and extended families, but we’re concerned about their health and wellbeing as well as our own. We may be juggling childcare, homeschooling, and our own work. Or we may be wondering how we’ll support ourselves through this. We may know those who are sick, or who are high-risk, or who are essential workers putting themselves at risk for our sake. We may have lost people close to us. And we may feel powerless to do anything.

The challenges of isolation and loneliness have become apparent over the past several months of social distancing. Not only are we physically separated from our friends and extended families, but we’re concerned about their health and wellbeing as well as our own. We may be juggling childcare, homeschooling, and our own work. Or we may be wondering how we’ll support ourselves through this. We may know those who are sick, or who are high-risk, or who are essential workers putting themselves at risk for our sake. We may have lost people close to us. And we may feel powerless to do anything. Last year on Mother's Day, I was driving through the Rocky Mountains, on my way from Oregon to Maine where my life was about to change forever. It was the first Mother's Day I had spent without my kids since they were born, and the first Mother's Day since my own mother had passed away. I yearned to call her to share the news of my latest adventure, as I always had during our frequent long-distance phone chats, but I knew I couldn’t. The following week, my daughter would bring my granddaughter into the world on the southern coast of Maine. The transcontinental journey I was on would end with the newest love of my life joining our family.

Last year on Mother's Day, I was driving through the Rocky Mountains, on my way from Oregon to Maine where my life was about to change forever. It was the first Mother's Day I had spent without my kids since they were born, and the first Mother's Day since my own mother had passed away. I yearned to call her to share the news of my latest adventure, as I always had during our frequent long-distance phone chats, but I knew I couldn’t. The following week, my daughter would bring my granddaughter into the world on the southern coast of Maine. The transcontinental journey I was on would end with the newest love of my life joining our family. It is the spring of 2020, and my senior year at Wellesley College is not at all what I imagined it would be like. Before concerns about COVID-19 led

It is the spring of 2020, and my senior year at Wellesley College is not at all what I imagined it would be like. Before concerns about COVID-19 led