The challenges of isolation and loneliness have become apparent over the past several months of social distancing. Not only are we physically separated from our friends and extended families, but we’re concerned about their health and wellbeing as well as our own. We may be juggling childcare, homeschooling, and our own work. Or we may be wondering how we’ll support ourselves through this. We may know those who are sick, or who are high-risk, or who are essential workers putting themselves at risk for our sake. We may have lost people close to us. And we may feel powerless to do anything.

The challenges of isolation and loneliness have become apparent over the past several months of social distancing. Not only are we physically separated from our friends and extended families, but we’re concerned about their health and wellbeing as well as our own. We may be juggling childcare, homeschooling, and our own work. Or we may be wondering how we’ll support ourselves through this. We may know those who are sick, or who are high-risk, or who are essential workers putting themselves at risk for our sake. We may have lost people close to us. And we may feel powerless to do anything.

The situations that we find ourselves in can be overwhelming, and can contribute to low mood, irritability, and other potential depressive symptoms. If these symptoms persist and severely impact your day-to-day functioning, it can be a good time to check in with your doctor or a therapist. Many providers have moved to telehealth during this time, so it’s possible to connect to extra support. But if you just notice your mood dropping a bit or you feel a bit unmotivated, you may want to try out new strategies to prevent further depressive symptoms or bounce back from these moments of low mood.

First of all, it’s important to acknowledge that this is a time of adjustment and loss. Many of us will experience normal mood fluctuations such as low mood and sadness related to the loss of life the way it used to be. As with any loss, reactions will come and go, and feel different from day to day. Being gentle with yourself and others is important for maintaining mental health. For example, focus on “good enough” instead of “perfect” or “how I would usually do this.” Think of tasks that help you to feel productive, need to be done, and give you joy, and engage in a mix of those things. Let go of getting everything done. When you do achieve something, celebrate it.

It’s also important to remember that every person is different and will have certain strategies that work better for them in maintaining mental health. Different circumstances and situations will call for different approaches. Consider this a time of experimentation: try new strategies, but don’t be afraid to give them up and use others if they don’t work for you.

Social support from family and friends can help to prevent symptoms of depression. The lack of close personal contact during this time of social distancing is a challenge and can lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness. While we may not be able to interact with one another in the ways we’re used to, there are plenty of ways to stay connected.

If you’re lucky enough to be social distancing with your family, take some time out to connect with your kids or spouse. Even small moments of connection can improve your mood. When it comes to technology, find what works best for you, whether it’s virtual parties or one-on-one chats with a friend. While social media is one way to connect, it may be less helpful than picking up the phone and calling or FaceTiming. And just as in life before, know your limits. Having time to yourself to recharge is still important, and if you’re feeling Zoom overload, it’s perfectly okay to say no to a virtual happy hour.

When you’re interacting with others or when you’re alone, don’t forget to notice the good or joyful moments — that can do a lot to improve your mood. Did you have a good laugh about something silly with your family? Did you get a sense of satisfaction from completing that puzzle that’s been sitting in your living room for years? Notice when those moments come up and what you’re doing, and look for opportunities to engage in more of them. Along those lines, you can start tracking three good things or three things that went well each day. In addition to writing these three things down, write what made them go well or what caused them. Research has demonstrated that doing this daily for a month can help to improve your mood and increase happiness.

Repetitive negative thinking can contribute to depressive symptoms, so it can be helpful to take time to notice thoughts that are connected to feelings of sadness, anger, fear, and other emotions that bring your mood down. Once you notice these thoughts you can make efforts to reframe them or focus your attention on more helpful ones. If you notice that a bothersome thought keeps coming up, see if you can switch it up. For example, “I’ll be stuck at home forever” could be turned into, “I feel stuck right now, and this is a temporary situation. I’m looking forward to seeing my dad after this is over.”

Taking care of your physical health can have a strong effect as well. You may see a lot of runners and bikers out in your neighborhood these days, and they’ve got the right idea. Exercise has been found to be effective in preventing depression. Just engaging in something active can help — check out streaming yoga or old-school Richard Simmons videos. Take a walk around your house or challenge yourself to a stair climb. It doesn’t matter what you do as long as you get moving, and your mood will likely improve as a result.

Though it can be hard to put down your phone or turn off the news, getting enough sleep (but not too much) can help keep your mood stable and make it easier to roll with the punches. If you’re having difficulty sleeping, work on improving your sleep hygiene. Start preparing an hour before bedtime by turning off screens, doing some relaxation, and clearing your head.

Finally, remember that it’s not about never feeling low — it’s about bouncing back from the low mood. Honor the fact that this is a difficult, sad, and anxiety-provoking time. Remind yourself that social distancing and staying at home are temporary. Think of other difficult times in your life and what strategies you used to get through those times. If we are mindful of our thoughts and intentional about the strategies we use throughout the day, we may be able to maintain good mental health — despite all of the challenges we’re facing.

Further resources:

- American Psychological Association’s Psychology Help Center

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America Helpful Expert Tips and Resources

Katherine R. Buchholz, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral research scientist working on depression prevention research at the Wellesley Centers for Women.

Depression is Prevalent but Prevention Programs Are Limited

Depression is Prevalent but Prevention Programs Are Limited Approaches & Recommendations

Approaches & Recommendations

killers flood your system buffering the pain. Neither of these reactions are under your conscious control. You are automatically protected.

killers flood your system buffering the pain. Neither of these reactions are under your conscious control. You are automatically protected.

Treating youth depression once it emerges may be much more distressing, and much less effective, than identifying early symptoms of illness and treating them before they develop into a full-blown disorder. Prevention approaches have the potential to reach a large number of adolescents, and may be more acceptable than treatment because services can be rendered in non-clinical settings (e.g., schools, primary care settings), and do not require adolescents to identify themselves as ill.

Treating youth depression once it emerges may be much more distressing, and much less effective, than identifying early symptoms of illness and treating them before they develop into a full-blown disorder. Prevention approaches have the potential to reach a large number of adolescents, and may be more acceptable than treatment because services can be rendered in non-clinical settings (e.g., schools, primary care settings), and do not require adolescents to identify themselves as ill.

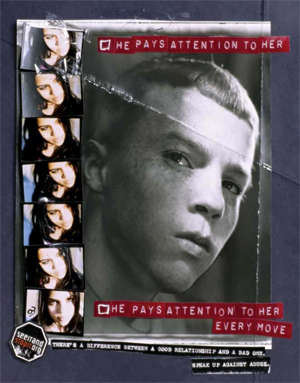

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.