At the beginning of my summer research internship, I’ll admit that I didn’t fully understand the impact of fathers talking to their teens about dating and sex. Why would fathers have a significant impact on teens’ sexual health if someone else, like their mother, already has the situation under control? However, after taking a deeper dive into Senior Research Scientist Jennifer M. Grossman, Ph.D.,’s interview data from fathers, mothers, and teens, I reevaluated my stance.

Through identifying key themes from the families in our sample, Dr. Grossman’s study—part of WCW’s Family, Sexuality, and Communication Research Initiative—aims to explore how fathers fit into conversations with their teens about dating and sex, and why it’s hard for some fathers to participate. The study’s findings will be used to develop an intervention program to help give fathers information, strategies, and peer support to surmount obstacles to talking with their teens and promote better sexual health for future generations.

Reflecting on my initial doubts, I can see why I didn’t have much faith in fathers’ ability to communicate with their teens—especially when it comes to taboo topics such as dating and sex. Women are often assumed to be more emotional, caring, and nurturing while fathers are assumed to have difficulty expressing their vulnerable side. Because of these pervasive stereotypes, it’s easy to see how mothers would be the ones to take the primary role and facilitate open conversations with their teens as they explore their sexuality.

Researchers may also lean into this assumption since the majority of prior studies on adolescent communication about dating and sex emphasize mothers’ roles. Even some mothers from our sample indicated that they should be the ones to take charge of these discussions—though they also resoundingly asserted that fathers’ roles are crucial. In the bigger picture, all of the familial support that teens can get in terms of dating and sex is shown to benefit their long-term health, but being mindful to include and value the male perspective could also prove beneficial to adolescents’ wellbeing and overall preparedness for healthy relationships.

That’s why I became especially interested in how fathers from our sample practice—or struggle to practice—open communication with their adolescents, as well as how teens from the same families picture an open dialogue.

In the bigger picture, all of the familial support that teens can get in terms of dating and sex is shown to benefit their long-term health, but being mindful to include and value the male perspective could also prove beneficial to adolescents’ wellbeing and overall preparedness for healthy relationships.

Fathers from our sample overwhelmingly said they believed that support and connection are important parts of their roles, and open communication is one way to foster these values. Specifically, dads saw it as their duty to give their sons tried-and-true advice that would help them avoid making the same mistakes they did. Additionally, some emphasized the benefits of giving daughters a window into the teenage boy’s perspective to help them better understand their potential dating partners.

Since the stereotypical teenager avoids talking to their parents at all costs, it might be surprising that teens also want open conversations with their dads. Over half of teens from our sample viewed support and connection, including open communication, as part of a father’s role. They wanted their dad to share his advice and experience, providing emotional support while respecting their comfort level and boundaries. A notable focus of the teen perspective is that they didn’t want to be judged or punished for sharing something of which their parents disapprove, such as being sexually active earlier than their family values dictate. As a whole, the data showed that both fathers and teens see some form of open dialogue as part of a father’s role in conversations about dating and sex.

Then why is it hard for many fathers to participate and share their advice? Fathers face many barriers such as embarrassment, discomfort, lack of support, and taboos. One obstacle that stands out to me is that some fathers lack an example from their own parents of how to approach these sensitive topics. The majority of fathers from our sample didn’t talk much or at all with their parents about dating and sex; instead, they learned through siblings, extended family, friends, or even through the media. In many ways, fathers are swimming upstream, trying to be more involved than their parents’ generation while lacking the tools and support they need.

Despite the challenges inhibiting fathers’ involvement in these discussions, many dads in our sample fought these barriers in order to support their teen’s best interests. In doing so, they stood up to the stereotypes, giving their children a healthy example by recognizing their own value and the power of their voice as a father. I’m hopeful that access to resources, such as the intervention program we plan to develop, will give fathers the tools they need to practice open communication and share what they learned from their teenage years. If the fathers of today set a healthy example for their teens, the fathers of tomorrow will be better equipped to talk with and support their children—making an impact that continues for generations to come.

Audrey DiMarco is a psychology major at Wellesley College graduating in 2024. She had the opportunity to work with Senior Research Scientist Jennifer M. Grossman, Ph.D., this past summer through the Class of 1967 Internship Program.

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist  The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.

The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.

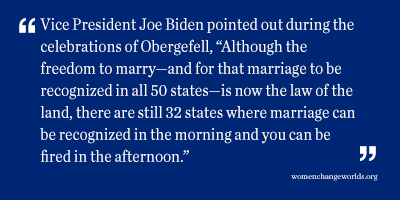

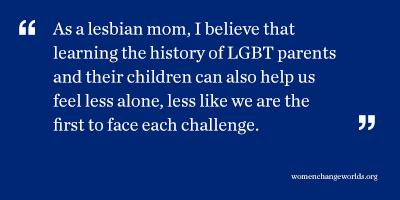

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot.

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot. Still, as

Still, as

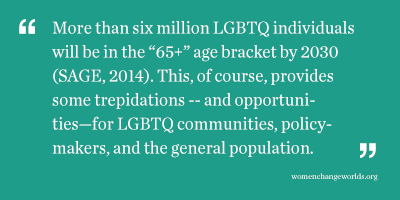

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex.

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex.