Dear Friends of WCW:

Dear Friends of WCW:

Happy New Year! I hope that your winter break was restful and rejuvenating. With a wrap on 2023, we leap headlong into 2024 with a sense of renewal and openness to what lies ahead. Our 2023 Research & Action Report highlighted some of our accomplishments from the previous year, as well as some of the new projects we are just starting. From our work to evaluate Planned Parenthood’s new sex ed curriculum to a new study of what home-based child care providers need to survive, we are excited about what is on the horizon—including a project that’s particularly close to my heart.

At the end of this week, I’ll be traveling to Liberia to train student intern data collectors for the Higher Education for Conservation Activity (HECA), a program funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). My role on this project is Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Lead, and my work ensures that more women, youth, people with disabilities, and people from rural, forest-dependent communities can participate in higher education programs related to forestry, biodiversity, and conservation. Liberia contains the largest remnant of the disappearing Upper Guinean Rainforest, and we are trying to train more people to take care of it, for the benefit of all. It is important that women's unique experiences, perspectives, and ideas inform this effort, along with those of others who have been sidelined in the past. To be involved with an effort to stem climate change is new for WCW, and I'm excited that I can represent both WCW and the College on this larger team effort. Stay tuned for a travelogue on Women Change Worlds in February!

Like many of you, I am tuned in to the world around us, and watching closely what 2024 might bring. For one thing, this is a presidential election year, which could affect us profoundly by shaping the conditions of our work, including government funding streams. Secondly, there are still multiple wars going on in the world, and how we show up for peace and justice, whether individually or institutionally, as a women-led, social justice, research and action organization, will be important. What's more, climate change is likely to continue to affect the weather and a whole lot more, and how we weigh in on this consequential topic will be an area of emerging importance. Last but not least, artificial intelligence (AI) is the new kid on the block, and we are just beginning to understand what new issues it will raise, affecting gender equality, social justice, and human wellbeing as it evolves in ways we can scarcely imagine today. I’m sure you can think of many other things to add to this list. It is a time of converging grand challenges, but that has never scared WCW! We are on it!

As we begin this year, I am thankful for all of you and all you do to support WCW. However grand the challenges may be, it is always the small, local, everyday actions that give solutions life and make change sustainable. And it is also our interventions on the discourses of society—the ways in which we make sure WCW's research and action is heard and considered by wider audiences—that have the potential to change hearts and minds and structures of power in a positive, humane direction. Your material support of our work makes it sustainable and increases its power to influence change. In the famous words of an African philosopher, “I am because we are, and because we are, I am.” Thank you!

Happy 2024,

Layli

Layli Maparyan, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College.

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

I spent the past semester working with Professor

I spent the past semester working with Professor  In my recently released book,

In my recently released book,  Hospitals and universities are facing challenges that many have never seen before as they respond to COVID-19. Universities are

Hospitals and universities are facing challenges that many have never seen before as they respond to COVID-19. Universities are  A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.

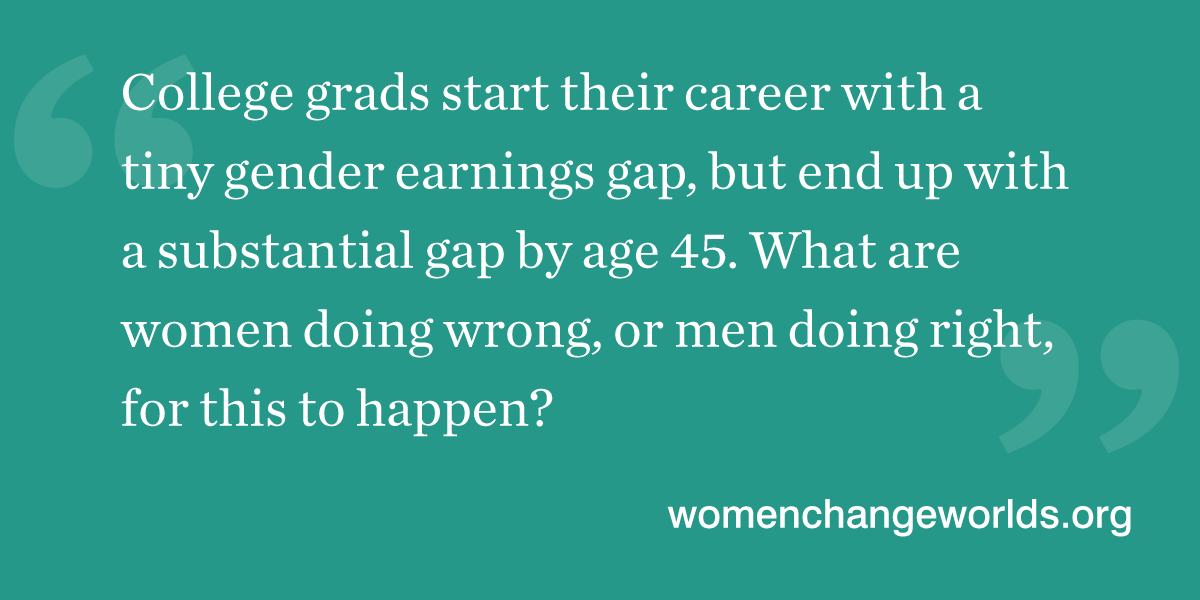

A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.  In 2019, Melissa Morabito, Ph.D.,

In 2019, Melissa Morabito, Ph.D.,  The long march towards progress is often one that extends across generations. The U.S.

The long march towards progress is often one that extends across generations. The U.S.  This week, Canada launched the

This week, Canada launched the  About twenty years ago, I received some unbearable news about a dear friend. A highly intelligent, strong, and beautiful woman of African-descent revealed to me that she contracted HIV as a result of having unprotected sex with a man who had the virus. Twenty years ago, I was convinced that the virus was an automatic death sentence for my friend. Thankfully, with advances in medical technology, not only is she still with us but she is healthy and thriving. However, keep in mind that she has the necessary resources that are needed in order to take care of herself, so she can successfully manage her overall health. She is middle class, has a good health insurance plan, has access to the appropriate health care, and has a supportive social network that encourages her to maintain her health.

About twenty years ago, I received some unbearable news about a dear friend. A highly intelligent, strong, and beautiful woman of African-descent revealed to me that she contracted HIV as a result of having unprotected sex with a man who had the virus. Twenty years ago, I was convinced that the virus was an automatic death sentence for my friend. Thankfully, with advances in medical technology, not only is she still with us but she is healthy and thriving. However, keep in mind that she has the necessary resources that are needed in order to take care of herself, so she can successfully manage her overall health. She is middle class, has a good health insurance plan, has access to the appropriate health care, and has a supportive social network that encourages her to maintain her health. Ph.D., is a former post-doctoral intern at the

Ph.D., is a former post-doctoral intern at the  We don’t live in an “either/or” world. Most non-sport institutions get this. It’s why Starbucks has unisex bathrooms, why there are forms to change your gender on government documents, why there is even a concept of “preferred pronouns.”

We don’t live in an “either/or” world. Most non-sport institutions get this. It’s why Starbucks has unisex bathrooms, why there are forms to change your gender on government documents, why there is even a concept of “preferred pronouns.” Indian sprinter

Indian sprinter  As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

As we enter 2018 with eager anticipation, it is a natural part of the transition into the new year to establish personal and career resolutions. Many business leaders consider ways to refresh the strategy for their organizations seeking to answer questions such as “How can my team help our organization achieve its goals with a greater impact?”

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives.

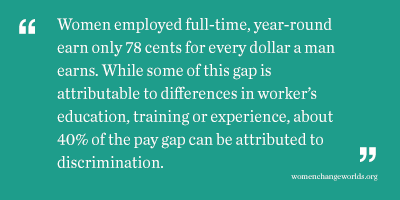

Finally, Capgemini enhanced our Women’s Leadership Development Program (WLDP) to ensure a positive impact on the development of our women leaders. As a three-month program designed to provide training, mentoring, career objective-setting, and coaching for women in North America, WLDP is a signature program of the company’s talent development initiatives. We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many

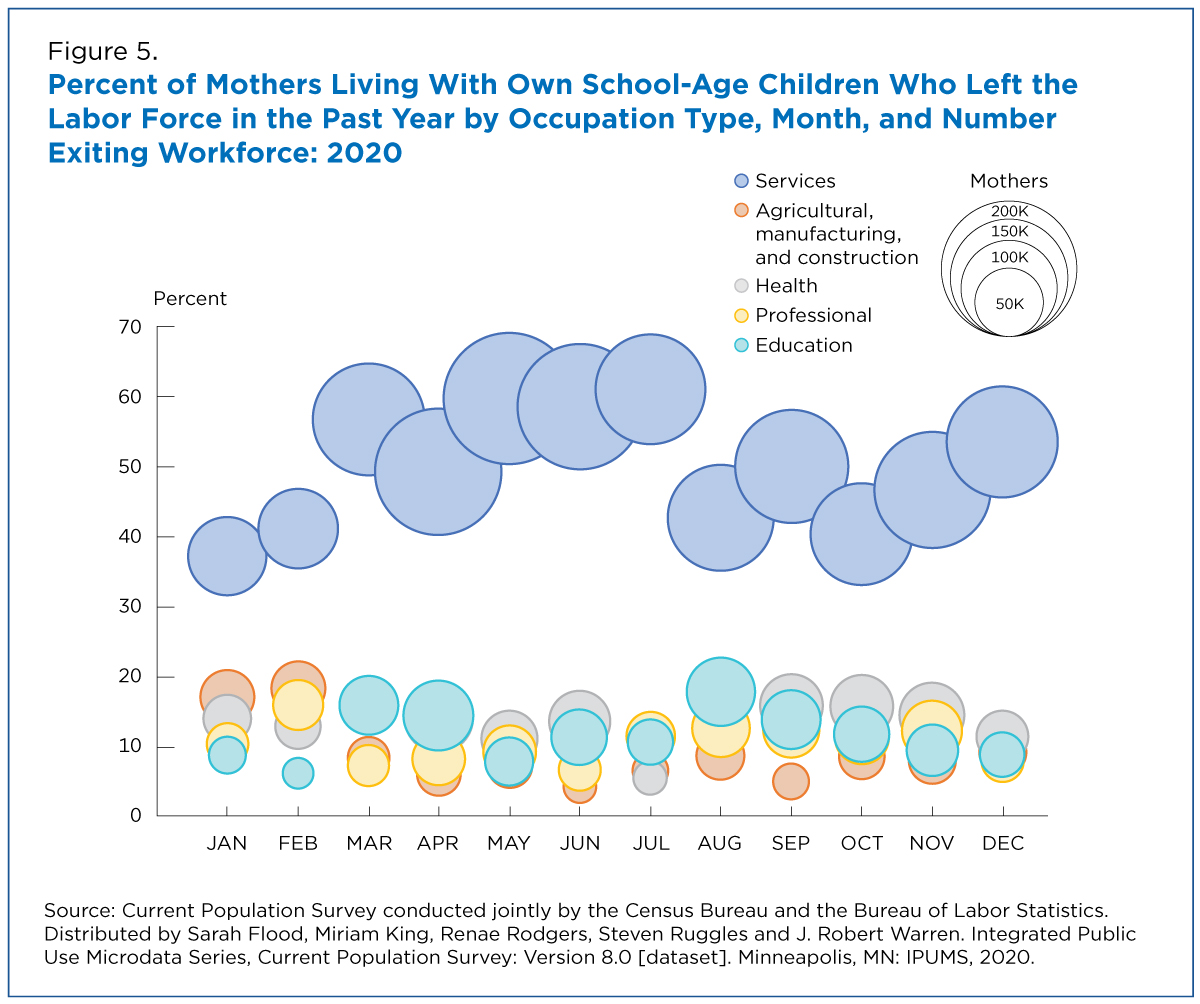

We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many  Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to

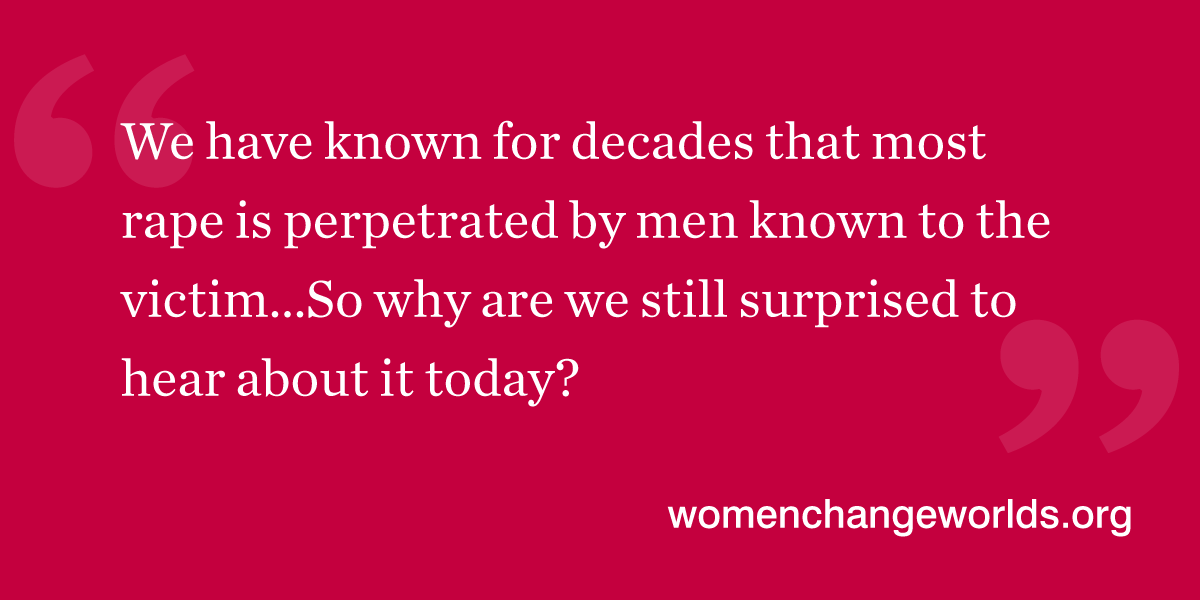

Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to  I applaud the strength and solidarity of the women (and men, too) who are asserting with the hashtag

I applaud the strength and solidarity of the women (and men, too) who are asserting with the hashtag  We must remember it is not only Hollywood producers who sexually assault and not only young actors who are the victims. The rapists and perpetrators of sexual assault include:

We must remember it is not only Hollywood producers who sexually assault and not only young actors who are the victims. The rapists and perpetrators of sexual assault include:

Mentorship was the reason I came to Wellesley College, all the way across the globe from Sri Lanka. Back in 2013 on the day of the United Nations’

Mentorship was the reason I came to Wellesley College, all the way across the globe from Sri Lanka. Back in 2013 on the day of the United Nations’

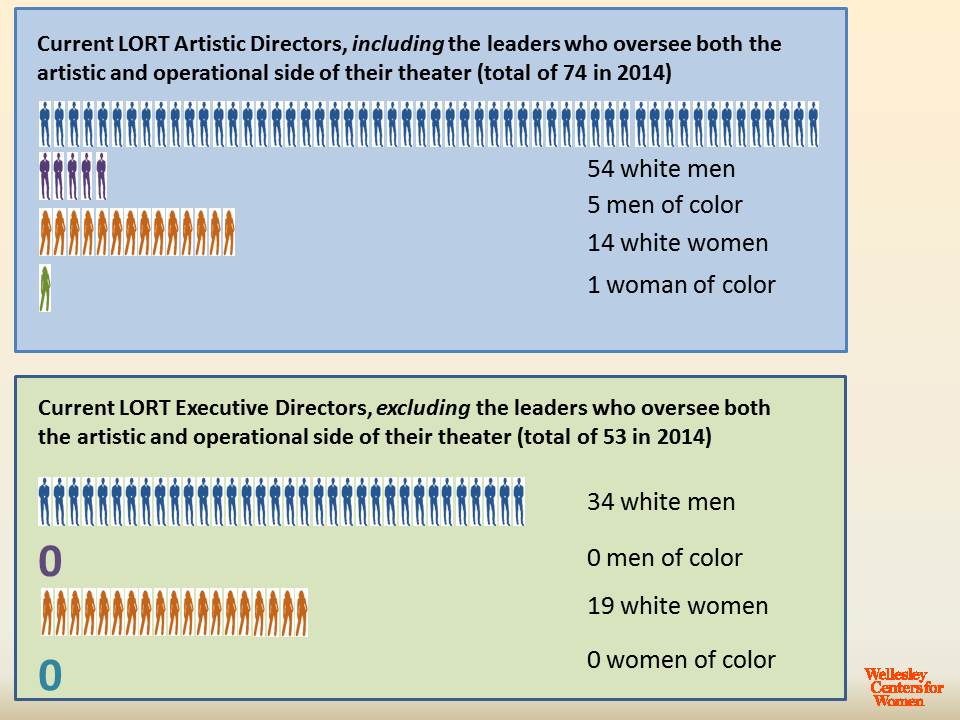

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot.

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot. Still, as

Still, as

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

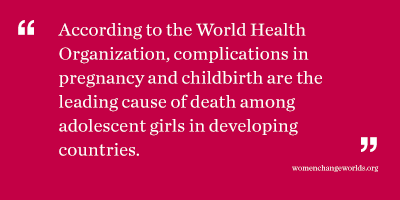

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

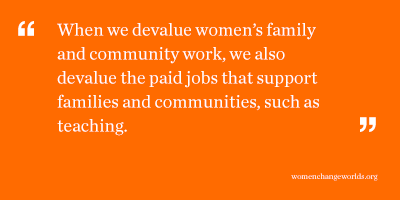

Service occupations, such as maids and housekeeping cleaners, personal care aides and child care workers, are the lowest paid of all broad occupational categories. This disproportionately affects the earnings of

Service occupations, such as maids and housekeeping cleaners, personal care aides and child care workers, are the lowest paid of all broad occupational categories. This disproportionately affects the earnings of  In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

Media coverage about social media has not been kind—often linking its use with cyberbullying, sexual predators, and depression or loneliness. But recent scholarship on new media demonstrates that interpersonal communication, online and offline, plays a vital role in integrating people into their communities by helping them build support, maintain ties, and promote trust. Social media is often used to escape from the pressures of life and alter moods, to secure an audience for self-disclosures, and to widen social networks and increase social capital. The

Media coverage about social media has not been kind—often linking its use with cyberbullying, sexual predators, and depression or loneliness. But recent scholarship on new media demonstrates that interpersonal communication, online and offline, plays a vital role in integrating people into their communities by helping them build support, maintain ties, and promote trust. Social media is often used to escape from the pressures of life and alter moods, to secure an audience for self-disclosures, and to widen social networks and increase social capital. The

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

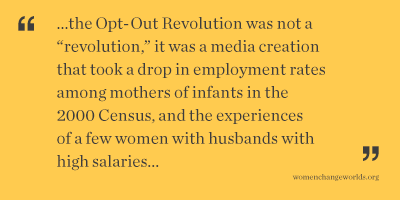

Meanwhile, media and popular attention remains focused on the message that women should solve the problems we face--of unfriendly workplaces, long work weeks, glass ceilings, and some men’s unequal sharing of household and parenting activities (often justified by workplaces that still think all men have wives who will support their husband’s careers)--by their personal, individual actions, rather than by our collective action to challenge the inequalities built into our economy, inequalities of gender, class and race. Women in the professions and in managerial jobs, who

Meanwhile, media and popular attention remains focused on the message that women should solve the problems we face--of unfriendly workplaces, long work weeks, glass ceilings, and some men’s unequal sharing of household and parenting activities (often justified by workplaces that still think all men have wives who will support their husband’s careers)--by their personal, individual actions, rather than by our collective action to challenge the inequalities built into our economy, inequalities of gender, class and race. Women in the professions and in managerial jobs, who

While

While

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

H.R.377) would strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

H.R.377) would strengthen the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

life-changing impact of our own

life-changing impact of our own