Substance abuse among women in Massachusetts is increasing dramatically. It is also a worldwide problem. Locally and globally we need to work for a public health model that is responsive to human rights concerns and effective in protecting families and communities.

The United Nations will be holding a General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) in New York in April, 2016. In preparation, a Global Civil Society Survey was conducted in spring 2015 to identify key areas of concern. Among the five areas to emerge from this process are drugs and health; drugs and crime; and protecting the human rights of women, children and communities in drug-related penal policies. Penal Reform International (PRI), based in the United Kingdom, is spearheading the collection of suggestions on alternatives to incarceration, and Andrea Huber, PRI’s policy director, forwarded me a request for input to this process.

This focus could not be timelier in terms of my work. For the past two years I have conducted research into women, crime, drugs and children in Massachusetts. I have analyzed caseload data of women seeking substance abuse services through the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, focusing primarily on mothers, and identifying those that are justice-involved. In 2013 alone, there were 33,000 admissions of women to treatment. Of these, almost one half had children under 18 years of age. Almost 30 percent of women’s admissions had some  form of justice-involvement (mostly probation). However, comparisons between justice-involved and non-justice-involved women revealed few differences on demographic and other characteristics. For example, their ages, maternal status, the number of children they have, their children’s ages, and the percentage living with their children.

form of justice-involvement (mostly probation). However, comparisons between justice-involved and non-justice-involved women revealed few differences on demographic and other characteristics. For example, their ages, maternal status, the number of children they have, their children’s ages, and the percentage living with their children.

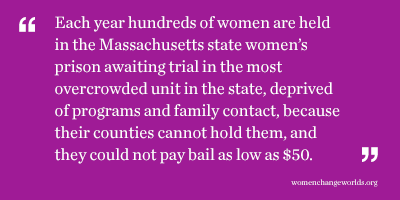

Also, I talked with women in residential addiction treatment houses--some of which permitted children to live with their mothers--and asked them about their history of treatment, the pros and cons of having their children with them in recovery, and whether justice-involvement had helped or hindered their recovery efforts. Although some women acknowledged that being arrested and locked up for a brief period of time might indeed have saved their lives, they had not experienced effective treatment while incarcerated; and over time their addictions had worsened. Women on probation face a different type of problem. If they experience a relapse they are caught up in negative, escalating sanctions. They are likely to be incarcerated--not because their original offenses warranted prison sentences--but because they have broken their conditions of probation. On the other hand, women in treatment facilities funded by the Department of Public Health are more likely to be encouraged to think about how and why they lapsed and to learn from those experiences.

These differences of approach between the public health and criminal justice paradigms are crucial because the average number of relapses for people in treatment in Massachusetts is around eleven. Gradually, the realization is growing that the criminal justice response to addictions, especially for women, is unworkable. Another reason to support the public health paradigm rather than justice-involvement is because of the universal lack of trauma-informed, effective treatment in prisons for women.

These findings clearly support the NGOs around the world that recommend treating health and human rights as the corner of international drug policy and call for a public health response through the following statements: “Civil society has clearly expressed the need for a public health response to the problems associated with drug use.” “There is a need for gender-sensitive services for women who use drugs...and to support pregnant women and women... with children.” [We need to] “Add a human rights lens to the drug policy conversation and include a gender lens.”

Erika Kates, Ph.D. is a senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College; she leads the Massachusetts Women's Justice Network.

one of the few surviving ‘Kinder.’ It was a somber occasion, both a tribute to the courage of those who survived and the generosity of the (mostly non-Jewish) families that took these children into their homes and raised them.

one of the few surviving ‘Kinder.’ It was a somber occasion, both a tribute to the courage of those who survived and the generosity of the (mostly non-Jewish) families that took these children into their homes and raised them. A week before my trip she informed me a Stolperstein for Marie Driesen was already in place, and that its installation had been arranged by a current owner of an apartment at the Schoeneberg address. Two weeks later my husband and I were warmly greeted by Hannelore and the owner, Baerbel. We looked at the Stolperstein in the sidewalk, and then sat at a table in Baerbel’s apartment and talked. We learned that around 1938, 37-39 Belziger Strasse had been designated as a Jewish building. This meant that all Jewish residents in the building were forced to take in other Jews as lodgers, and Jews from other buildings were forced to move into the apartments; measures that made it easier for them to be rounded up later. Baerbel, a retired geologist, had worked tirelessly to obtain documents on the 22 Jewish residents taken from that building, and she had a huge binder with files on each one. But she went further; she asked the 52 current residents to contribute to the cost of installing Stolperstein for them. Not a single person refused, and the installation had been filmed by local television.

A week before my trip she informed me a Stolperstein for Marie Driesen was already in place, and that its installation had been arranged by a current owner of an apartment at the Schoeneberg address. Two weeks later my husband and I were warmly greeted by Hannelore and the owner, Baerbel. We looked at the Stolperstein in the sidewalk, and then sat at a table in Baerbel’s apartment and talked. We learned that around 1938, 37-39 Belziger Strasse had been designated as a Jewish building. This meant that all Jewish residents in the building were forced to take in other Jews as lodgers, and Jews from other buildings were forced to move into the apartments; measures that made it easier for them to be rounded up later. Baerbel, a retired geologist, had worked tirelessly to obtain documents on the 22 Jewish residents taken from that building, and she had a huge binder with files on each one. But she went further; she asked the 52 current residents to contribute to the cost of installing Stolperstein for them. Not a single person refused, and the installation had been filmed by local television. Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty

Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty

The inadequacy of full-time, year-round minimum wage earnings to support a family. In 2009, single mothers earning the hourly minimum wage of $7.25 earned just over $15,000--well below the poverty level of $17,285 for a family of three. These earnings are far below the median U.S. family income (almost $50,000) and the median earnings of dual earning households (over $78,000).

The inadequacy of full-time, year-round minimum wage earnings to support a family. In 2009, single mothers earning the hourly minimum wage of $7.25 earned just over $15,000--well below the poverty level of $17,285 for a family of three. These earnings are far below the median U.S. family income (almost $50,000) and the median earnings of dual earning households (over $78,000). What can a good-looking, white woman with a Smith College degree and middle-class upbringing teach us about prisons in America?

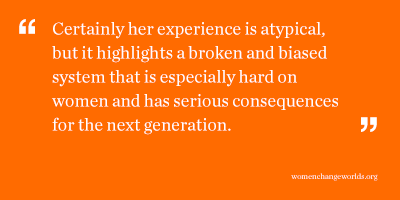

What can a good-looking, white woman with a Smith College degree and middle-class upbringing teach us about prisons in America? These lessons are realized just a few weeks before her scheduled release date, when she encounters Norma in the Chicago Correctional Center where she has been transported by “Con Air” to give testimony against another major player in the drug scheme. She overcomes her anger at Norma’s betrayal as together they cope with conditions far worse than the federal prisons from which they have come. In the Correctional Center, Kerman is horrified by the ‘crazy’ women and indifferent staff; the idleness and lack of daily structure; lack of daylight and exercise; inedible food and filthy conditions; and the inability to escape the constant noise and light.

These lessons are realized just a few weeks before her scheduled release date, when she encounters Norma in the Chicago Correctional Center where she has been transported by “Con Air” to give testimony against another major player in the drug scheme. She overcomes her anger at Norma’s betrayal as together they cope with conditions far worse than the federal prisons from which they have come. In the Correctional Center, Kerman is horrified by the ‘crazy’ women and indifferent staff; the idleness and lack of daily structure; lack of daylight and exercise; inedible food and filthy conditions; and the inability to escape the constant noise and light.

trauma; lack of education and training; sexual victimization by criminal justice personnel; and restricted eligibility for state benefits.

trauma; lack of education and training; sexual victimization by criminal justice personnel; and restricted eligibility for state benefits.