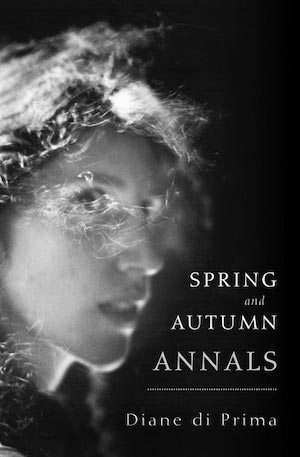

Spring and Autumn Annals By Diane di Prima

Reviewed by Jolie Braun

‘I woke to the sense that there was a lot to do, all of it beautiful, all of it urgent.’

A few years ago, I was researching poet Diane di Prima’s 1960s publishing venture, Poets Press, an underappreciated but important small press she used to publish the poetry of friends such as Audre Lorde, Allen Ginsberg, and A. B. Spellman, as well as her own work. My project led me to the University of Louisville, whose collection of di Prima’s papers contains material from this period. Looking through the boxes, I was struck by what was and wasn’t in her archives. There was no financial information, business records, or other official items of Poets Press. Instead, there were bits and pieces: mentions in letters and postcards, print runs and potential projects jotted down in notebooks, flyers for a book launch party. Such a motley assemblage is likely because di Prima’s life at the time was one of change and movement at odds with record keeping and saving materials. Spring and Autumn Annals, written during 1964–65 and published for the first time in its entirety this October (the one-year anniversary of di Prima’s passing), is a record of this extraordinarily active and tumultuous period in her life.

A few years ago, I was researching poet Diane di Prima’s 1960s publishing venture, Poets Press, an underappreciated but important small press she used to publish the poetry of friends such as Audre Lorde, Allen Ginsberg, and A. B. Spellman, as well as her own work. My project led me to the University of Louisville, whose collection of di Prima’s papers contains material from this period. Looking through the boxes, I was struck by what was and wasn’t in her archives. There was no financial information, business records, or other official items of Poets Press. Instead, there were bits and pieces: mentions in letters and postcards, print runs and potential projects jotted down in notebooks, flyers for a book launch party. Such a motley assemblage is likely because di Prima’s life at the time was one of change and movement at odds with record keeping and saving materials. Spring and Autumn Annals, written during 1964–65 and published for the first time in its entirety this October (the one-year anniversary of di Prima’s passing), is a record of this extraordinarily active and tumultuous period in her life.

She began keeping a journal after her friend, the dancer and Warhol-star Fred Herko, committed suicide on October 27, 1964. He was twenty-eight. Struggling to accept his death, she wrote daily for a year, timing her sessions by lighting a stick of incense and writing until it burned down. Spring and Autumn Annals, the result, is several things at once. Most immediately, it is an elegy for her friend and muse, about whom di Prima wrote many poems, including the collection Freddie Poems in 1972. In Annals, she portrays a charismatic and flawed figure whom she first met on a bench in Washington Square Park ten years earlier. Herko had trained at Juilliard as a pianist before deciding to pursue dance, studying at the American Ballet Theater School and with Merce Cunningham. He was handsome, gentle, and impulsive. She recalls his refrain: “Where’s your sense of adventure, di Prima?” A growing dependence on amphetamines during the last several months of Herko’s life led him to become increasingly unstable. As she recounts their shared apartments, early-morning and late-night conversations, coffee at diners, arguments, and heartbreaks, it becomes clear that for all the uncertainty during their twenties, they were constants in one another’s lives. She feels pangs of his absence, writing “The air is filled with things you would have made.”

The book’s secondary function is as memoir. “This was to be a book of remembrances,” she writes, as she records the events of daily life: running the press, doing household tasks, reading (Virgil, Gertrude Stein), learning Greek, and visiting with friends. Despite the busyness, there is a pervading sense of restlessness and searching, which may be part of what inspires her trips from New York City to the West Coast, dropping acid, and meditation. Di Prima often slips into earlier memories, and as the name suggests, Spring and Autumn Annals is organized by season, with the time of year guiding her recollections. During the fall, for instance, she describes a past Thanksgiving: “ … the shopping I did with Joan on Ninth Avenue. Those stalls at dusk, abundance of food, the chilly red light floating over the Hudson River. Oysters and filet mignon and even duck. Our shot at elegance. Three kinds of wine, soup, pastries, somehow sorrowful. All eaten with chilly hands, fingers always cold.” In July she recalls childhood vacations at the beach or lake, but about the present summer admits, “with the warm air pressing down on us and the sounds of kids out of school climbing on the stoops, jumping on the cars, the dust in the areaways, the cats languid, the flies coming in to see what the garbage is like, it becomes impossible to think or write of summer as an objective fact.” The seasons and their rituals frame di Prima’s portrait of her life in the moment; they mark the passage of time as she reflects on change.

The book’s secondary function is as memoir. “This was to be a book of remembrances,” she writes, as she records the events of daily life: running the press, doing household tasks, reading (Virgil, Gertrude Stein), learning Greek, and visiting with friends. Despite the busyness, there is a pervading sense of restlessness and searching, which may be part of what inspires her trips from New York City to the West Coast, dropping acid, and meditation. Di Prima often slips into earlier memories, and as the name suggests, Spring and Autumn Annals is organized by season, with the time of year guiding her recollections. During the fall, for instance, she describes a past Thanksgiving: “ … the shopping I did with Joan on Ninth Avenue. Those stalls at dusk, abundance of food, the chilly red light floating over the Hudson River. Oysters and filet mignon and even duck. Our shot at elegance. Three kinds of wine, soup, pastries, somehow sorrowful. All eaten with chilly hands, fingers always cold.” In July she recalls childhood vacations at the beach or lake, but about the present summer admits, “with the warm air pressing down on us and the sounds of kids out of school climbing on the stoops, jumping on the cars, the dust in the areaways, the cats languid, the flies coming in to see what the garbage is like, it becomes impossible to think or write of summer as an objective fact.” The seasons and their rituals frame di Prima’s portrait of her life in the moment; they mark the passage of time as she reflects on change.

Most significantly, Spring and Autumn Annals provides a window into the underground literary and art communities of the 1950s and 1960s and di Prima’s place within them. She is the most well-known of the women writers associated with the Beat Generation, but di Prima remains far less recognized than her male counterparts such as Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg. In his preface, poet and critic Ammiel Alcalay argues for di Prima’s wider recognition, not just for her writing but for the creative labor she performed during this era, particularly her advocacy of other writers and artists. She was engaged in a variety of projects, including editing and publishing the magazine The Floating Bear with LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka), co-founding The New York Poets Theatre (which featured performances by poets, dancers, and other artists), and publishing books through Poets Press (including The First Cities, Audre Lorde’s first collection). Narrated in Spring and Autumn Annals, these endeavors can be a source of anxiety, but they also inspire hope and excitement: “I woke to the sense that there was a lot to do, all of it beautiful, all of it urgent.” While di Prima is primarily linked to the Beats, the book is also a reminder of the interconnectedness of the mid-century literary movements, and her world is populated by an extensive network of individuals from these circles, including poet Frank O’Hara, writer Herbert Huncke, and artist George Herms. Although she was not fastidious about maintaining records for Poets Press, her activities during this period show a dedication to documenting and promoting the work of her friends and contemporaries.

Spring and Autumn Annals, however, is not a romanticized portrait of mid-century bohemian life. Money was often a problem for di Prima, as were rundown apartments and neglectful landlords. She worked odd jobs and frequently moved. Being a mother presented additional challenges. She was devoted to her children but also longed for more freedom and greater mobility. I was reminded of Kerouac’s famous taunt at a party during the 1950s: “di Prima, unless you forget about your babysitter, you’re never going to be a writer.” Perhaps the most perplexing obstacle in di Prima’s life was her husband, actor Alan Marlowe, whom she remembers disliking at their first meeting. They married in 1962, and their relationship was combative until their divorce in 1969.

As Spring and Autumn Annuals began as a journal, the writing is fragmented and impressionistic. Di Prima employs the kind of stylistic shorthand one might use when writing to a friend or for oneself: her thoughts are nonlinear, and people and situations are often discussed with little context. Yet there are many beautiful passages, and di Prima’s simple, direct language and use of rhythm and repetition highlight her skill as a poet. For example, considering her life after Herko’s death, she writes:

My life has split in two … I hold the present and future in one hand, the past in the other, patiently, endlessly trying to mesh the edges. To make some sense of it. To bridge. TO BRIDGE. No go. They slip in and out of different dimensions. The one becomes invisible when I turn to look at the other. Yet thinking of seashells in the rocks of the western mountains, the sea pebbles embedded in the soil some 8,000 feet in the air, I am comforted somewhat. As if the bridge will grow, will spin itself. Out of this intermittent buzzing pain.

Those new to her work may find Spring and Autumn Annals a difficult point of entry. There are several excellent starting places, fortunately, such as Recollections of My Life as a Woman (2001), a captivating and more straightforward memoir of her early life through 1965; Memoirs of a Beatnik (1969), a sensationalized autobiographical novel about her 1950s Greenwich Village life, published by Maurice Girodias of the avant-garde and erotic Olympia Press; and Pieces of a Song: Selected Poems (1990), which includes some of her best early poetry, at turns wry, spiritual, tough, and thoughtful. These writings capture roughly the same era in di Prima’s life, yet they have vastly different approaches and styles—Spring and Autumn Annals being the most experimental—and reading more than one offers compelling variations.

When she began Spring and Autumn Annals, di Prima was thirty and at a turning point her life. The book concludes in 1965 with her preparing to leave New York City, uncertain of her next steps. By the close of that decade, she had ended her relationship with Marlowe, shut down Poets Press, and stopped publishing The Floating Bear. She relocated to San Francisco and moved onto other pursuits, such as helping the activist group the Diggers distribute free food and writing her Revolutionary Letters poems, which she published in underground newspapers (a new edition will be released alongside Spring and Autumn Annals). Di Prima’s writing and interests continued to evolve over the years, and Spring and Autumn Annals is an important document of its time, adding detail to the portrait of a writer who participated in and supported a variety of artistic communities. When asked about the Beats during an interview in the 1990s, she replied, [I]t’s hard to think about oneself as a piece of a movement, because you’re yourself. The movement stays the movement, and you keep changing.”

Jolie Braun is the Curator of Modern Literature & Manuscripts at The Ohio State University.