The Mermaid and the Minotaur By Dorothy Dinnerstein

Reviewed by Vivian Gornick

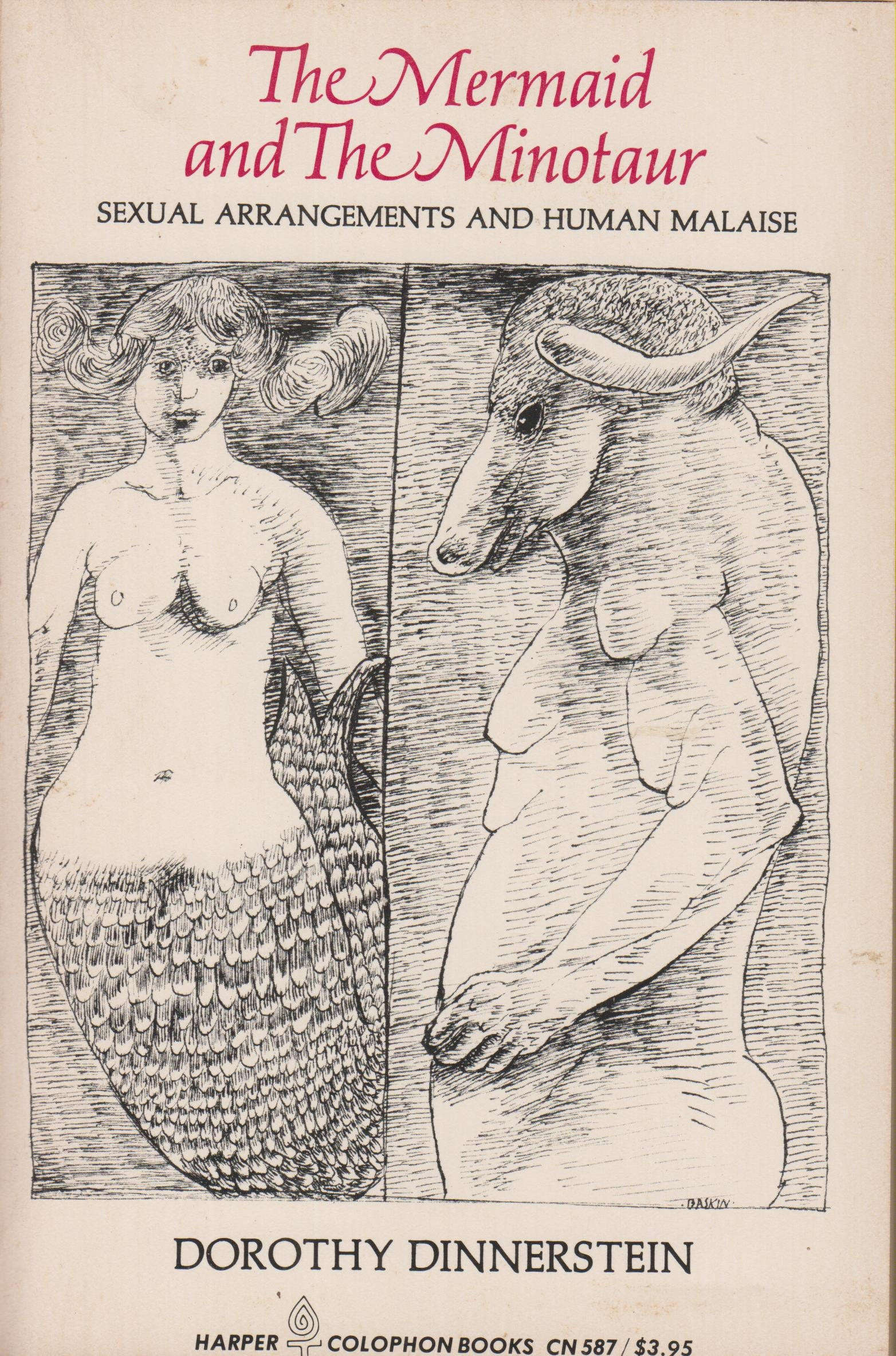

1977 paperback edition of Dinnerstein's seminal text.When Dorothy Dinnerstein’s The Mermaid and the Minotaur was published in 1976, many of my generation of Second Wave feminists felt as though we had suddenly been supplied with biblical text. Woman’s second-class position in society had long been traced to the ironclad shibboleth that motherhood defined her, but Dinnerstein mined the insight with such brilliance and originality that Mermaid quickly became a Book of Wisdom that anyone could live by.

1977 paperback edition of Dinnerstein's seminal text.When Dorothy Dinnerstein’s The Mermaid and the Minotaur was published in 1976, many of my generation of Second Wave feminists felt as though we had suddenly been supplied with biblical text. Woman’s second-class position in society had long been traced to the ironclad shibboleth that motherhood defined her, but Dinnerstein mined the insight with such brilliance and originality that Mermaid quickly became a Book of Wisdom that anyone could live by.

Forty-five years later, a new paperback edition published by Other Press has occasioned my rereading this work. Dinnerstein’s essential argument is that the major reason women and men can continue to make the sexual “arrangement” they always have made—that he be dominant and she subordinate—is that women alone have been, and are pretty much still, solely responsible for child-rearing. To this day, a woman is mainly “the parental person who is every infant’s first love, first witness, and first boss, the person who presides over the infant’s first encounters with the natural surround and who exists for the infant as the permanent representative of the flesh,” that which forever both attracts and repels. She is the embodiment of all the dangerously mixed feelings about childhood that we can never put behind us. She nurtures but hovers, protects but restricts, encourages but warns; anxiety is her middle name. Unlike the open invitation to aggress upon the world that the semi-absent father seems to extend—urging the fledgling person to simply spread its wings and fly—the mother’s invite turns on apprehensions that divide us from the longing to experience ourselves fully and freely. Who on earth would not willingly turn away from identification with such a compromise? We have made a world, Dinnerstein speculates, in which “female dominated childcare guarantees male insistence upon and female compliance with a double standard of sexual behavior.”

If from earliest life fatherhood, like motherhood, was associated with the all-important physical intimacy that is our introduction to human existence, the race as a whole would see that each of our parents is molded, differently but equally, by fear and desire, courage and cowardice, kindness and (in)competence. Should such a monumental change be achieved, the age-old “arrangement” between women and men would fall away, and all would take their rightful place in the domestic sphere as well as the world enterprise. Then we’d see more clearly who or what is responsible for the infantilism within that continually waylays our Sisyphean efforts at wholeness of being.

It all sounds so reasonable, doesn’t it? We see the problem; we see the solution. Why then does the culture’s ability to achieve consolidation between theory and practice continue to elude us?

This, actually, is the large preoccupation behind Dinnerstein’s lifelong work as a cognitive psychologist. Why, she asked for some good forty years, can human beings not act on their own behalf when, demonstrably, they see with a deal of shared clarity what might save them from their own worst selves. In the ongoing struggle for women’s rights (only one of the many injustices we are reluctant to part with), she sees this underlying conundrum writ large. More than two centuries have passed since Mary Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, two centuries in which, in ever growing numbers, millions have agreed on the need to admit women to the ranks of social and political equality; and yet, to the largest degree, the “arrangement” continues to hold sway. Again, we ask: why?

And here is where Dinnerstein proves herself prescient in her synthetic use of the wisdom derived from psychoanalysis, anthropology, myth, and fairy tale to make her case. Which is: We cannot correct a myriad of self-evident injustices, just as we cannot free ourselves of childhood, because we don’t really want to. We think we want to grow up, we say we want to grow up, we think we want equality, we say we want equality, but when it comes right down to it, the dread of individuation is greater than what we say we want. In fact, it is so great, it is not to be borne. Imagine beginning and ending only with oneself! Intolerable.

Yet, as the centuries progress, individuation seems exactly what millions do crave. The loss, as Dinnerstein puts it, “of infant oneness with the world” requires the steady consolation of believing we can forever stay as we were Before the Fall (otherwise known as leaving the womb)—and our “prevailing male-female arrangement” is “part of what we [believe we] have always been.” At the same time, much in us is resistant to remaining what we have always been; hence the never-ending liberationist movements that seem to approach revolution. On this score, we continue to be split down the middle, forever unable to resolve these powerful conflicts, either socially or personally.

It’s the ambivalence, seemingly inborn, that is so crippling. The therapeutic culture has demonstrated amply how impossibly hard it is to rid ourselves individually of the many garden variety neuroses easily traced back to childhood. Common experience reveals that fifteen minutes into psychotherapy we probably know everything we need to know, yet it will surely take decades, if not longer, to act on those original insights; we have lived too long with the disabilities that hobble us to simply give them up. Repeatedly, the fear of risking the unknown wins out over the abstract promise of walking free.

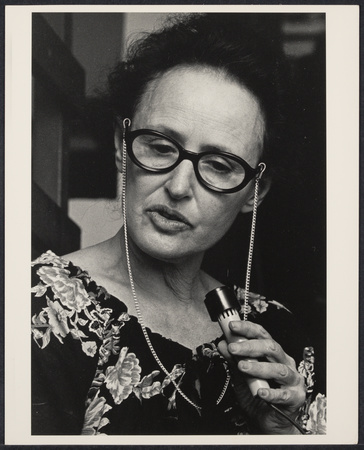

Dorothy Dinnerstein. Photo © Freda Leinwand, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard UniversityFor this pitiable situation Dinnerstein has large anger and even larger compassion. It pains her to have to conclude that, while the quintessence of human life is its “self-creating feature,” we, all too often, have refused to make use of this marvelous mechanism for righting the wrongs we so needlessly inflict on ourselves as well as one another. As the weary analyst might point out, as individuals we are sunk in what can only be called a symbiotic relationship to our personal neuroses. By the same token, Dinnerstein testifies that traditional relations between women and men also represent a symbiosis that we find “oppressive [but] are nonetheless ... frightened of giving up.” It might very well, she speculates, “take [us] forever to become sufficiently free of [its] influence.”

Dorothy Dinnerstein. Photo © Freda Leinwand, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard UniversityFor this pitiable situation Dinnerstein has large anger and even larger compassion. It pains her to have to conclude that, while the quintessence of human life is its “self-creating feature,” we, all too often, have refused to make use of this marvelous mechanism for righting the wrongs we so needlessly inflict on ourselves as well as one another. As the weary analyst might point out, as individuals we are sunk in what can only be called a symbiotic relationship to our personal neuroses. By the same token, Dinnerstein testifies that traditional relations between women and men also represent a symbiosis that we find “oppressive [but] are nonetheless ... frightened of giving up.” It might very well, she speculates, “take [us] forever to become sufficiently free of [its] influence.”

The beauty of The Mermaid and the Minotaur resides not in its intellectual excellence (although there is that in abundance) but rather in the poetic sympathy with which Dinnerstein puts pen to paper. Taut, pessimistic truths form its foundation: “Until we grow strong enough to renounce the pernicious prevailing forms of [this] collaboration between the sexes,” she writes, “both man and woman will remain semi-human, monstrous.” Yet a vein of love for all that we have and have not been, as well as all that we might yet be, runs through the entire book. Single-sex rearing, she mourns, “gives us boys who will grow reliably into childish men, unsure of their grasp on life’s primitive realities. And it gives us girls who will grow reliably into childish women, unsure of their right to full worldly adult status.”

Taut, pessimistic truths form its foundation … Yet a vein of love for all that we have and have not been, as well as all that we might yet be, runs through the entire book.

Ah, but there is hope as well as anxiety. On the one hand, very soon after birth, we are saddled with what will prove to be a lifelong fear of our own mortality. On the other hand, Dinnerstein observes, we are born ignorant of this fact; and she adds: “What we make of [it] depends on what happens before we discover them.” In short, the way life feels from the start will determine how well we do with these ur fears that threaten to bring us down. And here is where she ties it up: perhaps a father’s brazenly self-assured touch as well as a mother’s over sensitive one is wanted to complicate the weave of courage and protection the baby will be swaddled in.

Dinnerstein is not writing to accuse or demonize or bring men to the bar of sexist justice, she is writing to understand how everyone concerned suffers from the conventional “arrangement” between women and men. Inevitably, it is more in sorrow than in anger that she speaks of the need to end our mutual imprisonment inside the territory of single-sex parenting; that sorrow is never more in evidence than when she grieves over men’s abandonment of the free flow of their own tenderness, an emotion easily restored should they begin raising their own children.

More than four decades have gone by since Mermaid was first published. Over these passing years I have read the book three times, reviewed it twice, and contributed an introductory note to its first re-publication. Each time around I have prepared myself to find the book either mildly dated or severely time-worn, bereft of intellectual merit or emotional power or sheer writing pleasure. None of these expectations has ever materialized. In fact, the opposite has prevailed: Mermaid grows richer, more provocative, more profound with each reading. Repeatedly, it throws me back not only on my own history as a feminist—that is, someone for whom the struggle for women’s rights is integral to that of human rights—but as one for whom the contemplation of “outsiderness” has been a lifelong activity.

I grew up the youngest child in a large clan of Jewish immigrant working-class lefties for whom life on the periphery was a given, and, like Dinnerstein, came of age wondering: “Why was I born on the margin and what does it take to get to the center?” This has been a key sentence in my own development, one I am reminded of every time I reread this great work of social research and fullhearted empathy. Not a year goes by that I don’t put Mermaid into the hands of some young person (usually a woman) who reminds me of the glorious pleasure and pain one derives from thinking hard about one’s own actual experience.

Vivian Gornick is an American critic, journalist, essayist, and memoirist. Her books include Fierce Attachments, The Odd Woman and the City, and Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader. Taking a Long Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time, publishes this month from Verso.