Prime Suspects By Laurie Stone

My selections were random, the way you fall upon things in Pandemica, yet weirdly (or tellingly), all the female characters were made to stand for something—a phenomenon, a type, a cautionary example—apart from being a particular person.

Three things in the moment you love? I’ll start. The flat gray sky that is almost the same color as the snow-covered fields. The Chopin impromptu on the radio. A plaster parrot with a green back and a yellow breast, swinging on a tree outside the window. I love this parrot.

Some months ago, I was asked to describe a book I'd written in a sentence of any length. I didn’t write the sentence. I thought for a while the reason was the election and the pandemic. I don't know the reason. Instead, I’ve been thinking about writing I want to read. The sentences I want to read are little provocations that mount like a road accident.

And something else. If I am your reader, and you are reporting a scene of violently ordinary sexism, say the way males in a particular culture get to walk ahead and females by custom and possibly by law are required to jump over a cliff onto jagged rocks—a different woman every few minutes—and the thing you are talking to me about is the conversation the men are having as they walk ahead, deaf to the cries of the women on the cliffs, if you report this conversation, full of meaning to the men and to you, if you report this conversation without telling me as well how the rest of the scene is making you feel and what it is making you think about, if you do this, I will cease to be your reader.

This is not an example of cancel culture. The reader needs to fall in love with what the narrator is in love with, and how can you be in love with what the narrator is in love with if the narrator is in love with a world bent on your destruction? Cancel culture is when you arrive at this point and insist no one should read what you don’t want to read.

I streamed four shows over the past few weeks, all centering on women, two recently released and two older works I was curious to rewatch—to see how the female characters were understood in their time and think about who I was when I first saw them. My selections were random, the way you fall upon things in Pandemica, yet weirdly (or tellingly), all the female characters were made to stand for something—a phenomenon, a type, a cautionary example—apart from being a particular person.

Prime Suspect (Hulu), which began airing thirty years ago, stars Helen Mirren as London detective Jane Tennison, a character stunningly aware of other people and truly alive only while solving murders. The men on the force sneer and ma'am her to death, including in season one a doughy, improbable boyfriend, who walks out because she’s too busy chasing a serial killer to cook dinner for him. The show is mesmerizing, partly because of Mirren’s flinty and very sexy performance and partly because it inspects what still goes on—a woman with exceptional ability having to fight against a world that doesn't want her with as much energy as she pursues criminals.

The series comes off dated at times, especially in the extra amount of punishment meted out to Jane, something the creators seem oblivious of—showing her frustrated, thwarted, starved, and denied less because of sexism than because it's how women are understood to exist in the world, fair or unfair. Whenever female characters get screwed and screwed again, despite their efforts individually or collectively, it tells the viewer not to worry, the world you woke up in remains intact. I don't think this undermining of a show’s own analysis is standard practice anymore, but it was the case for a very long time when I covered film and TV in the eighties and nineties, that denying female characters gratification, with a sadistic edge, was a glaring trend that didn't often get called what it is.

Watching the show now, I kept wondering what it would be like to speak the way Mirren does here—softly and with almost no visible emotion. Then I remembered there is freedom in knowing you won’t change. The other day the man I live with said, “I probably won't shovel snow in my late eighties.” I said, "Why not?"

For no reason I can point to, one night we decided to watch Darling (Criterion), directed by John Schlesinger and with a screenplay by Frederic Raphael. In 1965, when the movie was released, it was something everyone talked about, said to be charting the cynicism of the world and the headlong, icy way modern women went after what they wanted. They did? Seeing it now, the question you can’t help asking is: Why does Julie Christie wear so many scarves over her bouffant hair? Julie’s character, Diana Scott, is looking for a way to dodge domesticity and get to the party, and her way is through men, which leads back to some house or other, although she doesn’t foresee this.

To be honest, the movie did stir memories of the time when we all married Italian princes we had had like no conversations with and dressed up in gowns to eat alone when our husbands went to Rome to visit mama. We were bored. So bored. Bored, bored bored. Everyone adjusted their voices to the clipped, fake upper-class, crackly accent of Audrey Hepburn. Even Julie Christie! We represented the fallen world and the vacuousness of the vacuum that had opened between drab, postwar England and the swinging whatever poking up from the dead land. We (girls) represented vacuousness in every movie made, because that's what we were made to represent. (Maybe not every movie. Don’t quote me.) Directors looked at us with distaste and fascination. Obviously.

The best moment in the film: Julie beginning her affair with Dirk Bogarde by sticking a finger in his mouth as he sleeps on a train. Bogarde is beautiful and great to watch. Laurence Harvey, also a love interest, ghouls around, his mouth an unbroken line. And there we were, pacing the ancient stone paths of the castle we'd finally moved into, breaking hearts like the porcelain figurines we smashed to the floor, and wondering how in hell we were going to get out of this one. Julie got an Academy Award that year for best actress.

The past few days I’ve been thinking about my teacher Morris Dickstein, who died recently, and who in 1968 taught a seminar on Blake at Columbia University. 1968 is only a few years after 1965, but they might as well have been different eras. The Blake seminar so vibrated with the love Morris felt for the great poet of freedom and rebellion and with the love Morris felt for the students who came each week to watch ideas about life shoot from his forehead we would never forget the feeling of being there. Everyone in the class moved toward each other. One was a man named Lenny who also became a professor, and in that setting, I think we could foresee that in all the decades to come we’d find ourselves from time to time at a bar, talking as if it would always be 1968.

In the seminar, we read every word Blake wrote. We were invited to Morris's apartment. It was a time when students and faculty mixed, and if you were a student you were in awe of everything about professors. Over the years I would cross paths with Morris at screenings and book events, and I would always be happy to see him. No one knows the resonances they produce when they teach a class and the class becomes a thing. No one knows these resonances can last nearly a lifetime.

If not for the women’s movement—fully up and running by ’68—we might all have become Diana Scotts. I had friends who didn't eat in their apartments as a way to be anorexic. I would open their refrigerators, and there would be leftovers from expensive restaurants I was jealous they had gone to, and on top of bits of this and that they had scooped into aluminum tins would grow lovely, mossy topiaries. Because they didn't eat in their apartments.

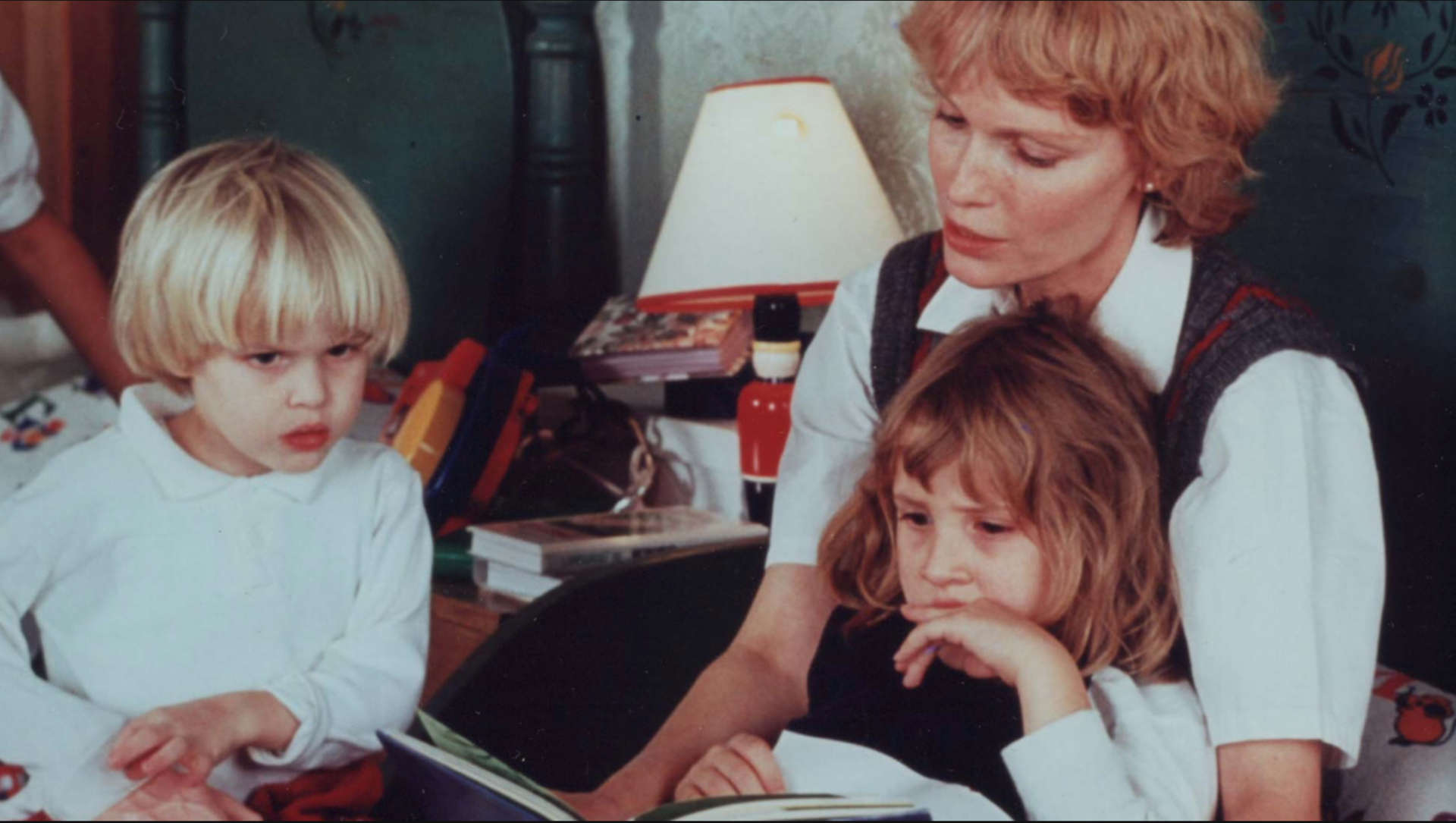

Mia Farrow with Ronan (left) and Dylan (right), from HBO's Allen v. Farrow. Photo credits to HBO.Watching the four-part documentary Allen v. Farrow (HBO), the Diana Scott approach to going places floated to mind as Mia’s romantic relationships were reviewed, the way she tucked herself into the lives of men with mastery in their work while remaining insecure about her own: Frank Sinatra, André Previn, Woody Allen. Maybe in the life of every Diana Scott eventually arrives a boyfriend who will marry your daughter.

Mia Farrow with Ronan (left) and Dylan (right), from HBO's Allen v. Farrow. Photo credits to HBO.Watching the four-part documentary Allen v. Farrow (HBO), the Diana Scott approach to going places floated to mind as Mia’s romantic relationships were reviewed, the way she tucked herself into the lives of men with mastery in their work while remaining insecure about her own: Frank Sinatra, André Previn, Woody Allen. Maybe in the life of every Diana Scott eventually arrives a boyfriend who will marry your daughter.

Mia’s face, bathed in light in the interviews, is still amazed at the way the world works, no evidence of irony or a sense of humor, although there is the deadpan delivery of the fact that Previn fell in love with her best friend when she was off making a movie, and that ended their marriage. Mia doesn’t mention she did the same thing years earlier to Dory Previn when she got together with André, a detail that might have shown viewers she, too, knows that people fuck the people they want to fuck. (The filmmakers and Mia also refer to Sun-Yi Previn as a “freshman in college” when Mia discovers the affair, which reads as eighteen instead of Previn’s actual age of twenty-one.) In a sense, by editing out information, Farrow and the filmmakers turn Mia into a symbol, in this case: Woman Betrayed, so that Allen will come across as an especially ruthless liar. They didn’t need to.

He does that job all by himself, appearing deeply manipulative in footage and interviews, a man who for so long has lived unimpeded in a world of his own making he seems to believe the lies he tells himself about his actions toward his family. Feeling disgust toward him as a person, I was curious to see what I’d think of his work, so I rewatched the “cloning from the nose” sequence in Sleeper (1973).

It’s hilarious. What can I tell you? With comedy, you either laugh or you don’t laugh. And if you laugh, you’ve laughed. The sequence is a Marx Brothers’ routine of schmendricks pretending to be experts at something. In this case Allen and Diane Keaton are doctors, claiming they can restore the state’s dictator by growing him from his nose, the only remnant left from an explosion. In an operating theater, stalling for time, Keaton lays out the shoes and gloves and pants the dictator will grow into from the nose, and part of the reason this is funny is that we do this all the time, stall before starting a project by loading software we won’t need, or sharpening pencils, or cleaning the studio—hoping the project will grow itself from an idea we’ve jotted on a napkin.

In other news, I regrouted the floor of the upstairs bathroom the serial-killer former owners had painted a green so absent of hope plants died there. I painted the walls the pearl gray of a moody ocean sky. The grout was too far gone to clean, so I mixed up fresh grout and went at it. The man I live with came to the door and said, “Did you read the instructions on the box?” I said, "What a good idea. Would you mind letting me know what they say?” I used to let my dog off the leash in Riverside Park, and when he would wander too far for me to see him and I would be shouting for him like a lunatic, I felt like I was going to die of fear, and I thought the dog was me in his indifference to control.

The last film I want to talk about is Nomadland (Netflix, directed by Chloé Zhao), and if you admire it, maybe skip this section. I thought the movie was dull. It couldn't find anything interesting in the people it asked us to spend time with, as if having pointed views, or talents, or interests would subvert their function as illustrations.

Illustrations of what? Disappointment in their system of government? In the inequities of wealth and opportunities for employment? In the way life ineluctably dwindles to lessness and bewilderment, no matter what you plan or don't plan? Viewing characters as sociological cases insults them and underpins the film's sentimentality. You can hear it in the heart-tugging music. And see it in the many times we see houseless main-character Fern cleaning something with a dirty rag.

The movie feels like an essay without a specific topic, and although Frances McDormand as Fern is fun to watch no matter what she does, she seems angry about having to move from joyless scene to joyless scene. Even the nice-looking food served at the Thanksgiving dinner Fern goes to looks like it wants to kill itself as a way to leave the table.

The interesting thing about Fern is that, apart from economic conditions, we really don't know why any of the things that have happened to her happened to her. The husband is a set of propositions: I married, we worked, he died. Nothing of their relationship is revealed, no sense of them together, and then the Shakespeare sonnet she recites meant to carry some ghostly load of meaning it can’t.

She's shut off from most of the people she interacts with, which seems understandable, given they aren't very compelling for one reason or another. What does she want other than to avoid people? I don't think she knows, and this, too, is interesting, but the movie doesn't want you to find Fern's lostness in herself interesting. It wants her, again, to stand for a social phenomenon.

At its most intriguing, the movie is a study in truculent aloneness. I liked Fern rejecting a slot in the Thanksgiving family and in her sister's suburban world. But I don't think the movie wants you to see it as a study in truculence. Even if you do, what does Fern want that she can't get: enough money to live without dependence on anyone else? Maybe, but then the movie would have had to make a better case for solitude instead of the tepid one it makes for communality.

Yesterday I sold the metal stool I'd bought in Arizona for some damn reason and that the man I live with had never liked. A moment ago, another man came to mind, who had caused me pain in love, and I found myself thinking: I hope you are right now feeling pain in love. I wondered if I really felt this way. I was far from the heat of that time, yet I could summon the memory if I wanted to. Flies have appeared on the railings surrounding the deck. You spray them with whatever, and a minute later they have returned, like resentment.

Bits of glass glint up in the soil above where last year we dug out trash the serial killers had dumped on our land. The plan is to cover them with wood chips. This year I will accept the plants people offer me and garden again in the I don’t really know how this works. If I had to know what I was doing before doing it, I wouldn't do anything.

For just this day the temperatures will reach the sixties, and I feel a stirring without direction. It’s like entering an elevator and hearing only part of the story before people get out. Do you have a spare room? Are there ants there? What is the Wi-Fi password? On the road I walk, I pass a house owned by a priest I once met who has recently died. I remember the bulbs that bloomed here last year: iris, lilies, daffodils, and tulips, and they will bloom again. Already there are buds on the forsythia, and today I saw a cardinal hop along the branch of a tree. On this property is a small house in addition to the regular house, a small house the size of a playhouse with a miniature front porch, and it is painted a shade of blue so dazzlingly unlike anything else on the road, I call it peacock blue, even though I don't know if this color exists.

Laurie Stone is a regular contributor to the Women’s Review of Books. She is author most recently of Everything is Personal, Notes on Now, which features several essays that originally appeared in the WRB.