Olivia on the Record: A Radical Experiment in Women’s Music By Ginny Berson

Reviewed by Shane Snowdon

In its greatest success, Olivia Records nurtured inner and, for a time, outer lesbian worlds that helped women change our selves and the larger culture for the better.

Back cover photo of Olivia's first album, I Know You Know by Meg Christian. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren).This baby-boomer lesbian’s bruised heart skipped a beat on encountering Olivia on the Record, a herstory of the first seven years (1973–80) of lesbian feminist collective Olivia Records, by co-founder Ginny Berson. Olivia was central to “women’s music,” the combination of recordings, concerts, and festivals that sparked and supported a so-called lesbian culture that changed the wider one in ways now widely taken for granted. Not for nothing was Olivia’s biggest hit, from golden-voiced Cris Williamson, titled The Changer and the Changed. The presence of this 1975 album in a glove box of cassettes or milk crate of records signaled a lesbian or bi owner who might well have come out—in an auditorium or bed—to its tunes.

Back cover photo of Olivia's first album, I Know You Know by Meg Christian. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren).This baby-boomer lesbian’s bruised heart skipped a beat on encountering Olivia on the Record, a herstory of the first seven years (1973–80) of lesbian feminist collective Olivia Records, by co-founder Ginny Berson. Olivia was central to “women’s music,” the combination of recordings, concerts, and festivals that sparked and supported a so-called lesbian culture that changed the wider one in ways now widely taken for granted. Not for nothing was Olivia’s biggest hit, from golden-voiced Cris Williamson, titled The Changer and the Changed. The presence of this 1975 album in a glove box of cassettes or milk crate of records signaled a lesbian or bi owner who might well have come out—in an auditorium or bed—to its tunes.

And our mass coming-out in the early seventies was world-changing. Inspired much more often by the civil rights, countercultural, anti-war, and women’s movements than by Stonewall (a fact frustratingly ignored by the many LGBTQ+ histories that portray the New York uprising as the birthplace of queer liberation), newly out lesbians like Berson joined women whom she respectfully calls “old gays” in weaving a lesbian culture and movement much more diverse and transformative than is now perceived. But, at the risk of sounding like a tiresome forebear telling and retelling the tale of trudging miles through snowy fields to a one-room schoolhouse with only a baked potato for warmth and sustenance, I have to say that being out in that era was no picnic.

In a world uncomprehending and unsupportive at best, hostile and punitive at worst, we dykes had to create our own picnic. And this we did, literally, at the music festivals where we congregated, in every state, at a time with few sizable women’s gatherings of any kind. Now decried by some as transphobic, and misleadingly equated with boomer lesbian feminism as a whole, the festivals gave thousands of us a sorely needed sense of our individual and collective beauty, courage, and strength. We dreamed of reproducing back home the compassion and community we experienced at these events.

And, in fact, festival energy—and lesbian energy in general—was often channeled into crucial social services (including the first domestic violence shelters and rape crisis centers) and into wide-ranging advocacy (around choice, childcare, employment, abuse, harassment, and health, but also affordable housing, welfare rights, prison reform, support for immigrants, freedom from violence, and more). Lesbians disproportionately founded and powered groundbreaking social justice non-profits that have, in many cases, endured and expanded, albeit with their origins and originators usually forgotten.

Berson’s book scarcely mentions the festivals and does not attempt to portray women’s music as a whole. For that, fortunately, we have the meticulous work of historian Bonnie J. Morris (including Eden Built by Eves and The Disappearing L), Jamie Anderson’s evocative An Army of Lovers, and Dee Mosbacher’s splendid documentary, Radical Harmonies, (co-produced by women’s music figures Boden Sandstrom, Margie Adam, and June Millington). But with a wit and brevity that counter the stereotype of the grim, droning boomer lesbian, Berson details other key elements of 1970s lesbian feminism in a book that is engaging, revealing, and important.

As the title of Mosbacher’s film suggests, women’s music was radical in both intention and effect. It is this underlying radicalism on which Berson’s memoir focuses, spotlighting two prominent lesbian feminist collectives that deployed art in service of revolution. Olivia Records, she recounts, was a direct descendant of the DC-based collective The Furies, which she joined in her early twenties and which was legendary in its 1971–72 lifespan for producing a cutting-edge, eponymous newspaper, eagerly read nationwide. The twelve Furies, who lived and worked together, saw themselves as a revolutionary vanguard, committed to toppling the US government, and patriarchy overall, via theory-building, cadre formation, and perhaps, if necessary, violence.

These extraordinarily talented and energetic women—who included Rita Mae Brown, JEB, and Charlotte Bunch, to indulge in a star-tripping callout they would have eschewed—are beginning to receive some of the attention they deserve. The rowhouse The Furies called home is on the National Register of Historic Places, astoundingly. And a superb 2020 documentary by Jacqueline Rhodes, Once a Fury, animates the animated beliefs of these lesbian revolutionaries, who ranged in age from 18 to 28. They were, as Berson writes, “vibrating with the knowledge that everything we thought was wrong with us was not, and we knew who was responsible and why this was so.”

Berson offers a handy bulleted list of the collective’s fundamental principles, aimed at rebuking the “straight women’s movement” of the day, which seemed to share Betty Friedan’s view of lesbians as a “lavender menace.” (The Furies, in return, considered the straight movement “zigzag and haphazard.”) The collective’s basic beliefs, she writes, were:

“Sexism is the root of all other oppressions”

“Lesbianism is the essential revolutionary component in upending the system”

“Because lesbians are outcasts from every culture, we will be natural allies across, class, race, and national lines”

“The personal is political . . . and the political is personal . . . sexual attraction and orientation are socially constructed rather than biologically determined”

“Lesbianism is a political choice”

Ginny Berson (center) speaks at a Furies forum in 1972. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren).These principles (which had much in common with those of New York City’s Radicalesbians) were fleshed out in well-wrought Furies articles, many by Berson, steeped in the authors’ voracious reading of revolutionary theory and close examination of radical practice. While it’s possible to dispute their passionate opinions, it can’t be denied that they were thinking hard and freshly about questions highly relevant today. What is the root of oppression, if one can be determined? What changemaking power does marginalized status confer? Can oppressed outcasts unite in meaningful alliances? How should political convictions shape choices about work and domestic life? These questions, which could be torn from today’s social media headlines, were avidly debated by the collective and thousands of other lesbians nationwide.

Ginny Berson (center) speaks at a Furies forum in 1972. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren).These principles (which had much in common with those of New York City’s Radicalesbians) were fleshed out in well-wrought Furies articles, many by Berson, steeped in the authors’ voracious reading of revolutionary theory and close examination of radical practice. While it’s possible to dispute their passionate opinions, it can’t be denied that they were thinking hard and freshly about questions highly relevant today. What is the root of oppression, if one can be determined? What changemaking power does marginalized status confer? Can oppressed outcasts unite in meaningful alliances? How should political convictions shape choices about work and domestic life? These questions, which could be torn from today’s social media headlines, were avidly debated by the collective and thousands of other lesbians nationwide.

As for the significance of lesbianism itself, The Furies were among many lesbians who strongly, often successfully, encouraged women to make love with other women as a revolutionary, patriarchy-terminating act. Women’s sexual fluidity was no secret to the lesbians of the day, who replaced the old bar pick-up line “Don’t die wondering” with an admonition that served goals both political and personal: “Feminism is the theory—lesbianism is the practice.” (My students, who have been exposed only to the “we can’t help it” argument that sexual orientation is solely biologically determined, are shocked when I quote this staple of boomer lesbian thought, attributed to Ti-Grace Atkinson.)

The Furies—in Berson’s words, “young, angry, separatist, liberated, sure of ourselves, arrogant”—nonetheless realized that they needed “friends we could turn to, who would stand with us or at least for us, who might be willing to hide us if it came to that.” So they gave each other “assignments of people to organize,” and one of Berson’s was “old gay” Meg Christian, who was charming straight and lesbian clubgoers alike with formidable guitar skills and lyrics that, to those in the know, were plainly woman-loving in a music world that considered them career-ending. (Angela Davis’s important Blues Legacies and Black Feminism honors the brave Black women who, until the 1970s, were virtually the only musicians to mention a love that otherwise dared not sing its name.) The recruiter and her assignment became lovers—but The Furies collective dissolved soon after.

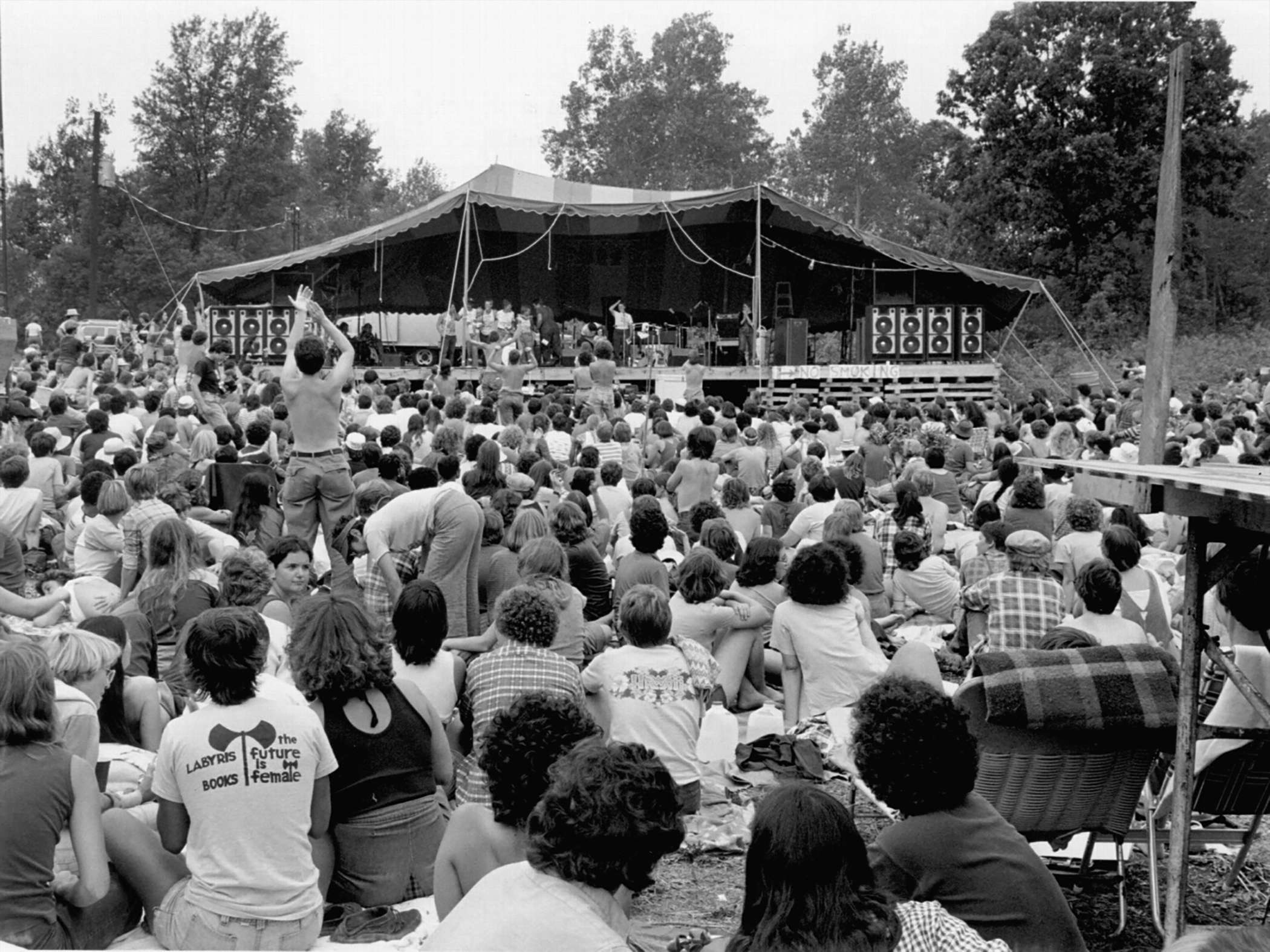

The Michigan Womyn's Music Festival in 1977. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren). Undaunted, Berson and Christian decided to create a new collective to advance radical lesbian feminism. While mulling options, they met Cris Williamson, whose lyrics indicated she knew a thing or two about woman-loving. They shared their dilemma with her over homecooked tuna noodle casserole—official downscale entree of Lesbian Nation—and were intrigued by her response: “Why don’t you start a women’s record company?”

The Michigan Womyn's Music Festival in 1977. Copyright 2021 JEB (Joan E. Biren). Undaunted, Berson and Christian decided to create a new collective to advance radical lesbian feminism. While mulling options, they met Cris Williamson, whose lyrics indicated she knew a thing or two about woman-loving. They shared their dilemma with her over homecooked tuna noodle casserole—official downscale entree of Lesbian Nation—and were intrigued by her response: “Why don’t you start a women’s record company?”

With three other women, Berson and Christian did just that in 1973, writing a founding womynifesto poignant in its grand, earnest vision:

This record company was started by Lesbian feminists to provide a means of equalizing economic/cultural inequalities . . . [W]omen, and therefore lesbians, are oppressed by the heterosexual and capitalistic institutions already in existence and we are committed to finding ways . . . of alleviating class, race, and heterosexual privilege. Because women have been denied the means of communicating their music and their culture, we intend to seek out and reward women’s musical achievements. Finally, we are committed to producing quality recordings of quality music.

Berson explains how this was to be accomplished:

We wanted to create an alternative economic institution that would eventually enable us to control all the means of production and to employ hundreds or thousands of women in well-paying jobs, doing meaningful work, with opportunities to learn new skills and to become part of the decision-making collective . . . I believed that we would create a model for feminism that would be irresistible. “This is what feminism looks like? I want in.”

Living out these aspirations in Olivia’s early days, Berson was “in heaven.” “What the right wing said about us was true—we did have an agenda and I was always recruiting,” she writes. “I felt like I was Ginny Appleseed, spreading the gospel of lesbian feminism.”

Spoiler alert: the collective’s gospel did not shatter heterosexuality or capitalism. But it definitely bore fruit. Producing forty-plus albums and selling over a million of them, Olivia nurtured inner and, for a time, outer lesbian worlds that helped women change ourselves and the larger culture for the better. (No longer a collective, Olivia today produces cruises—yes, seagoing cruises—during which those worlds are re-created for boomer lesbians and tickled younger women.) Although this outcome was far short of the women’s vision, it proved an amazing accomplishment, particularly as draining inter-lesbian conflicts arose.

These were so frequent that Berson’s narrative becomes a compendium of clashes, compiled by an author increasingly alienated by them. Some of the first conflicts emerged in 1976 on a tour produced by Olivia that featured Williamson, Christian, virtuosic singer/songwriter/pianist Margie Adam, and progressive vocalist Holly Near, an acoustic quartet known as the Fab Four of women’s music. There was unanimity that free childcare and ASL interpreting should always be provided, the latter a decision that would have wide influence. But should men be allowed to attend, despite the discomfort of many women? Should ticket prices be set for maximum accessibility, at the risk of devaluing the labor of those creating the events? Arguments over gnarly issues like these were combined with heavy substance use—and romances that produced both exhilaration and grief.

To an extent likely unique among social movements, lesbians of the day were deeply energized in their activism by love for one another (including, contrary to dour stereotype, what Berson accurately terms “hot and joyous sex”). But the erotic excitement arising from our work together could also damage it seriously. Berson notes this as a political problem, and also testifies to its personal cost: Christian left their four-year relationship to become involved with her Fab Four colleague Holly Near, who had identified as straight.

The pairing wowed women’s music audiences—Near hadn’t died wondering, and was practicing theory! Berson was appalled and ashamed by the anger and jealousy she felt. She found it unacceptable to be so affected by “emotions that seemed to belong to patriarchal ideas”—and when the women of Olivia were frightened or sad, she explains, “our attitude was ‘just deal with it.’” (This approach was far from uncommon among boomer lesbian activists.) She even remained a collective member, alongside Christian, for four more years. But, she relates, “something fundamental changed for me,” as it did for many idealistic lesbians whose love and work combinations had unhappy endings.

Her disappointment was intensified by incoming “horizontal hostility.” As Olivia gained more visibility, released more albums, employed more women, and made more money (if never remotely enough to attain financial security), the collective was confronted by other lesbians about nearly every aspect of their work. The Olives, as they styled themselves, dutifully met with their critics, and even had a laugh when one group, unaware of their heritage, quoted a Furies article to dictate proper lesbian feminist behavior. But the hostility ultimately took a huge toll on Berson, who speaks for countless other scarred boomer lesbians in writing ruefully, “I became cynical about the Women’s Movement and about the lesbian community . . . I had not believed that lesbians could be so cruel to each other.”

But she was not always resistant to criticism of Olivia, particularly around class. Even meeting with a group that attacked Christian for penning, and her for distributing, a Valentine’s song alluding to “dining and dancing” (ironically, it was written for Berson in better days), she sympathized with the women’s sensitivity to classist language. In fact, one of her book’s greatest revelations for many readers may be the attention that class received from The Furies, Olivia, and many of the era’s other lesbians, in incessant discussions almost inconceivable today.

Readers may also be surprised by Olivia’s fierce defense of transgender women, including one of their collective members, engineer Sandy Stone. (Targeted later in Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire, Stone penned the landmark essay “The Empire Strikes Back” in response.) True, the collective’s stance did not represent widespread lesbian thinking at the time. But it highlights a fact often ignored when boomer lesbians are stereotyped as clueless TERFs: as Amherst’s Jen Manion has pointed out in these pages, our relentless, multifaceted challenges to traditional gender conceptions did much to create “the gender turn.” (It is no coincidence that Judith Butler is a boomer lesbian.)

Berson also contradicts the stereotype of boomer lesbians as uncaring about race. As she writes, we engaged with it regularly and sincerely—but often unskillfully, to put it mildly. The Furies strove to be anti-racist, were civil rights activists, and felt themselves to be in solidarity with the Black Panthers, whom they sought to emulate around the oppression of lesbians. Olivia, also all-white in its early years, sought to record Black performers, engage Black listeners, and recruit Black collective members. But these efforts had very limited success, and many of Berson’s tales of well-meaning anti-racist efforts gone wrong echo today’s struggles.

These challenges were just a few of those with which the collective wrestled. Independent record companies have always been fiendishly difficult to sustain. Collectives, too, are famously demanding, with tortuous deliberations over equitable compensation and work assignments; the women paid themselves modestly and shared living expenses, but never enjoyed financial security. And when they weren’t discussing class, race, and external criticisms, they were earnestly pondering (not unrelated) internal questions, like whether the photo proposed for an album cover too closely resembled a patriarchal glam shot.

For good reason, Berson seems glum as she condenses the events of her last years with Olivia into a few chapter-ettes, ending the book abruptly with her 1980 departure from the collective. But she offers a wistful epilogue that, despite all, pays tribute to the joy and far-reaching impact of women’s music.

No reader could accuse Berson of being a subtle, lyrical writer; she is direct and plainspoken, like the poet Judy Grahn, whom she much admires. She is winningly candid, but seldom introspective, saying little about her family or inner life. And she is not always kind, as when she needlessly mentions a woman’s bipolar illness, exhibits oddly little compassion for Black musician Gwen Avery, whose life was tragically shadowed by addiction, and engages in some horizontal hostility of her own, dissing Fab Four icon Margie Adam for her birth in a “mostly white” community and elegant bearing.

And yet Berson’s book is a must-read, a powerful reminder that boomer lesbian feminists grappled with major questions in ways that could be invaluable today. Although she and the rest of us seem at high risk of cancellation as we near the end of our lives, might there be gifts in studying our energetic engagement—an impressive fifty years ago—with race, class, gender, sexuality, socialism, collectivity, and much more?

Don’t die wondering, I say. And don’t let us die wondering if we will be seen as the bold, if flawed, changemakers we were.

Shane Snowdon served as editor/publisher of the national feminist journal Sojourner, headed several women’s health groups, and led feminist and LGBTQ+ advocacy and education for nearly twenty years at the University of California. She is now a visiting scholar at the Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center and the Five Colleges Women’s Studies Research Center.