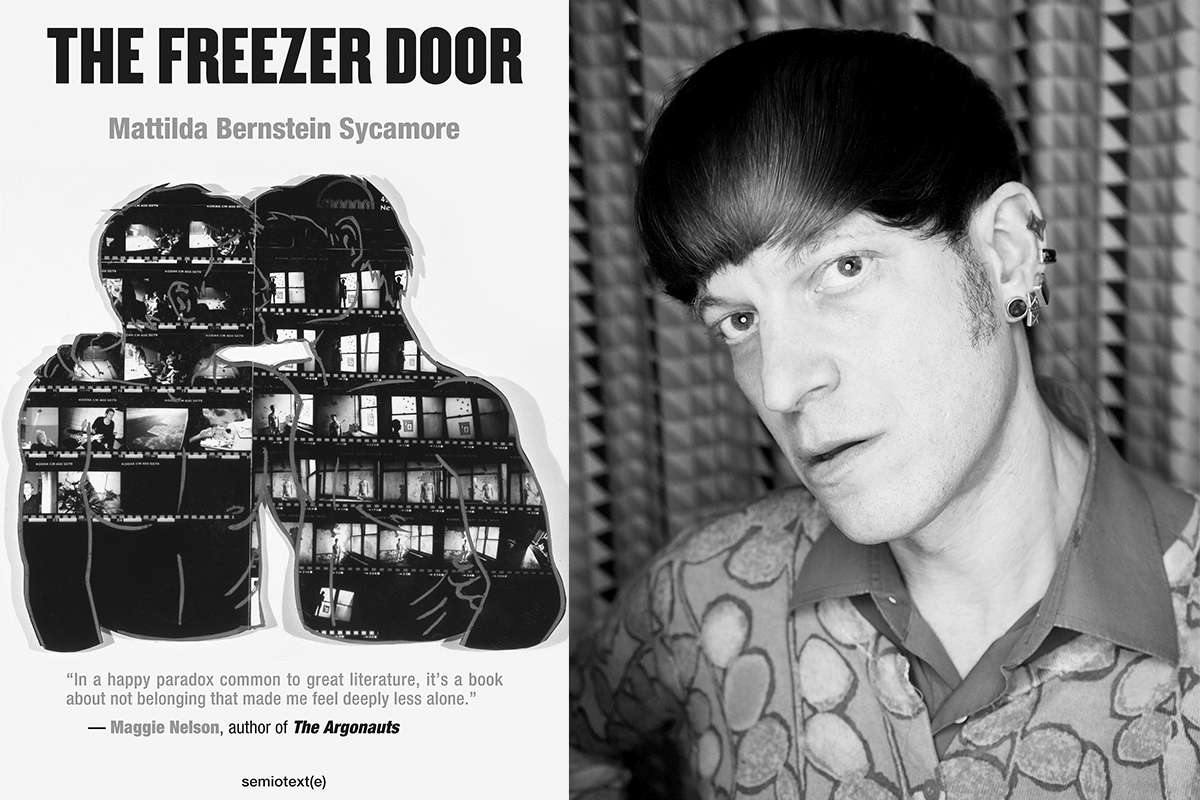

The Freezer Door By Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

Reviewed by Kathleen Rooney

It’s easy to see the pandemic as a rupture with the past. In March of 2020 we entered a new epoch, and yet, in many ways, the imperatives of social distancing are continuous with what came before: a shrinking public sphere, diminished opportunities for meaningful social interaction. Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s The Freezer Door is an intimate exploration of desire and its impossibility, as well as a critique of the waning possibilities for communal engagement with desire in everyday experience. A longtime activist and critic of cultural conformity, Sycamore identified these problems, particularly as they relate to queer communities, long before COVID, but this new book enters a world in which they feel more poignant than ever. As Sycamore herself has joked in videos and interviews, “I wrote a book about alienation and then everything got worse.”

It’s easy to see the pandemic as a rupture with the past. In March of 2020 we entered a new epoch, and yet, in many ways, the imperatives of social distancing are continuous with what came before: a shrinking public sphere, diminished opportunities for meaningful social interaction. Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s The Freezer Door is an intimate exploration of desire and its impossibility, as well as a critique of the waning possibilities for communal engagement with desire in everyday experience. A longtime activist and critic of cultural conformity, Sycamore identified these problems, particularly as they relate to queer communities, long before COVID, but this new book enters a world in which they feel more poignant than ever. As Sycamore herself has joked in videos and interviews, “I wrote a book about alienation and then everything got worse.”

Sycamore is the author of three novels and a memoir, as well as the editor of five anthologies, including the collection Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots? Flaming Challenges to Masculinity, Objectification, and the Desire to Conform. Like her previous work, The Freezer Door challenges the culture of queer assimilationism and documents her own search for sexual and intellectual intimacy. This deceptively slim volume is a slow read in the best possible way. I wanted to underline practically every sentence, and Sycamore strews her poetic fluidity with an almost overwhelming abundance of aphoristic utterances. A sampling: “Every gay bar is an accidental comedy routine. The best comedy routine is the one that takes itself seriously”; “I don’t want to become the cops, I want to end policing in all its forms”; “A sexual revolution without a political revolution isn’t a revolution at all, it’s just consumer choice branded as liberation.”

As seems fitting for a work that aims to challenge the very idea of the mainstream, Sycamore’s lyrical writing flows like stormwater, expressing her concern that “queer spaces have become places where the illusion of critical thinking hides the policing of thought,” and clarifying her desires: “I don’t want any team to win, I want to end winning.” This is an anarchic and unruly, yet dreamy and languid, meditation in fragments, full of unexpected juxtapositions and white space, in the tradition of such works as The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson and Socialist Realism by Trisha Low. The leapfrogging sections blend concrete personal experience and abstract theory to explore AIDS, cruising, trauma, loneliness, and connection.

Gentrification—particularly the cultural whitewashing and social isolation it produces—is one of the major objects of Sycamore’s critical gaze. Seattle, where Sycamore currently resides, receives a much-deserved dose of her disappointment. “This city that is and isn’t a city,” she writes, “but I guess that’s what every city is becoming now, a destination to imagine what imagination might be like, except for the lack.” If the marginalized don’t get washed out, they are pressured to blend in, adopting the trappings of the dominant culture. “When anything becomes homogenous, there’s a problem,” she writes. “When anything becomes so homogenous that people don’t even think about it, that’s worse.”

Like a latter-day, radically queer Jane Jacobs, Sycamore offers a biting appraisal of cosmopolitan existence for the twenty-first century. “The dream of urban living has always meant a density of experience,” she writes, “that random moment on the street that changes you. But now, when people say increasing the density, they mean building more luxury housing for new arrivals who only want an urban lifestyle with a walled-off suburban mentality—keep away difference, avoid unplanned interaction, don’t talk to anyone on the street because this might be dangerous.” She shines her wit like a flashlight on all that darkens her bright vision of what urban life should and shouldn’t be. For example, Sycamore is doing stretches, leaning on the exterior of a random apartment building, when “some fag wearing a backwards floral baseball cap tries to give me the straight gay attitude” for trespassing. The building is pretentiously named Onyx, although, “there’s nothing onyx—the building is grey, tan, and beige—it’s like Florida meets the supermarket.”

Sycamore slings plenty of zingers, and her targets are righteous, but she’s a lover, not a hater—a lover of trust, of beauty, and of genuine connection in all its forms, not only between romantic partners but between people and their friends, people and their architecture, people and trees, and on and on. What stuns me about her criticism is its gentleness—the ways she finds to be forceful but not harmful, always punching up, so to speak, or really not even punching at all, only highlighting blind spots and inviting her readers to open their eyes to more than the restricted array of consumerist possibilities that late capitalism presents as our only options. “I wonder if I’m the only person who still goes outside thinking something magnificent and unexpected might happen,” she writes in one of many sentences that encourage the reader to wonder too, and not just about that question, but to engage in more wonder in general.

If the book opens us up to wonder and to the unexpected, one of its strategies is its formal subversions, such as the titular “freezer door.” The already broken narrative is periodically interrupted by a dialogue taking place inside a freezer between an ice cube and an ice cube tray. The two discuss global warming, elections, the Supreme Court, gentrification, and a number of other pressing present-day problems. In doing so, they raise issues of freedom and community, safety and risk. “The only open relationship is the open door, says the ice cube tray.”

When the ice cube asks, “Why do people hate poetry,” the ice cube tray replies “Because it’s like us.” There are a lot of different ways a reader could take this fanciful back and forth, but one of the most liberating seems to be that, in a system that reduces lived experience to a set of commercial preferences that can be easily marketed to, and that boxes people into the tyranny of narratives inoffensive to the status quo, poetry can be a means of dismantling linguistic traps and offering a greater array of prospects for thinking and being. As Franco “Bifo” Berardi writes in The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance—another recent might-as-well-just-dip-the-whole-book-in-highlighter manifesto I happened to encounter shortly before The Freezer Door—“as deregulated predatory capitalism is destroying the future of the planet and of social life, poetry is going to play a new game: the game of reactivating the social body.” Poetry, and poetic books like Sycamore’s, put forth the necessary strategies to open the freezer door. One of the many wondrous aspects of Sycamore’s approach becomes not only what she’s saying, but how she’s saying it.

That said, as Sycamore notes, “uncritical consumption of critical engagement is still uncritical engagement,” and there are aspects of her book that some readers may find hard to appreciate. That, too, seems to be part of her intent: to invite readers to reset the way they gauge their own taste and what does and does not strike them as offensive. She uses the word “faggot” a great deal (advisedly and informedly, and to continue her critique of assimilationist gayness and internalized homophobia) and writes quite explicitly about fucking strangers in public parks and bathrooms. Some audiences possessed of “an overinvestment in middle-class norms” might find this material obscene, but that’s partly her point.

Rather than employing taboo and transgression as ends unto themselves, Sycamore transgresses in order to urge her audience to interrogate their almost-invisible suppositions and so-called civil decorum. She subverts the hypocrisies that tend to make people—especially self-described liberal people—uncomfortable, particularly the trend among American cities’ mainstream citizens to profess support for diversity while really favoring a bland and superficial aesthetic with little actual politics behind it. Sycamore’s strategic obscenity suggests that the real obscenity might lie elsewhere, like in trying to deny and erase difference because of the alternative it poses to putative good taste or consumerist decency.

“Part of the dream of queer is that it potentially has no opposite. Straight is the opposite of gay. Queer is a rejection of both.” The Freezer Door stands as a call to open the door and take a gamble on what might be outside—to reject the illusion of safety and try instead for a re-enchantment of everything, a magic that can only happen by reaching beyond “walled-off insufficiency.”

Kathleen Rooney is the author, most recently, of the novels Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s, 2017) and Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey (Penguin, 2020).