Research & Action Report Spring/Summer 2013

Educators can make a difference in preventing gender-based violence

Among Nan Stein’s contributions to the literature on sexual harassment and gender violence in schools are the first survey in the country on peer-to-peer sexual harassment in schools (1979-80); her book, Classrooms and Courtrooms: Facing Sexual Harassment in K-12 Schools; and three teaching guides1. Currently, she is working on the third stage of a study, Shifting Boundaries, which evaluates classroom lessons and school-wide interventions in middle schools intended to reduce sexual harassment and precursors to teen dating violence.

The White House and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan have both issued recent communications calling educators’ attention to your study, Shifting Boundaries. Tell us about that study and what makes it unique.

My research partner2 and I have been doing research in middle schools since 2005. We are funded by the National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice. Ours is the first randomized, controlled trial of middle school students on the issue of teen dating violence. Most research on this subject has focused on older students in eighth grade or high school; our study focuses on sixth and seventh graders.

It’s unique for those reasons, and for its rigorous design, which includes random assignment of schools to different versions of the lessons and interventions. We created a set of classroom interventions consisting of between four and six class lessons, depending on grade level, and a set of three school-wide or building interventions, which require administrative support but no class time. Some schools received the classroom lessons only, other schools got the school-wide interventions only, a third set of schools got the classroom lessons plus the school-wide interventions, and the fourth—the control group—received no interventions. Afterward, students were surveyed for their knowledge of the laws and consequences related to sexual harassment and dating violence, their attitudes towards these sorts of behaviors, their intention to avoid being perpetrators of violence, and their intentions to intervene as bystanders.

Our original research was conducted with 1,678 students in 123 classrooms across seven middle schools in three school districts in the greater Cleveland, OH area between 2005–2007. At the conclusion of those lessons, we formed focus groups with the students to learn which components of the lessons worked best.

We then applied for and received an expanded grant to conduct more research with added elements in the New York City schools, where 117 classrooms in 30 middle schools completed the interventions between 2008 and 2010. We collected evaluation data from nearly 2,700 students, who completed surveys administered before the interventions, immediately afterward, and about six-months post-interventions. We followed up with focus groups, with the adults who taught the lessons—teachers, drug and alcohol counselors, and so on—as well as with the students.

How would you summarize your findings?

In both studies we found that a comprehensive school initiative was effective in reducing sexual harassment and dating violence up to six months later. For example, in the New York study, both the combination of the classroom lessons and school-wide interventions—and the school-wide interventions alone—led to between 32 and 47 percent lower peer sexual violence, even six months later.

What’s the significance of those recent communications from the White House and the Department of Education about Shifting Boundaries?

Clearly, they’re invitations to state and local school administrations to start using our Shifting Boundaries lessons and interventions. The White House communication listed Shifting Boundaries among the latest research in support of the reauthorized Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) signed by President Obama this past March. In addition, in his letter to chief state school officers, Secretary Duncan’s statement, “Research shows that schools can make a difference in preventing violence and other forms of gender-based violence,” is footnoted (#10) directly to our study. These are both very exciting developments for our research and they go a long way to validating the effectiveness of Shifting Boundaries. This is very gratifying and promising.

Additionally, Shifting Boundaries can be relatively easy to implement. All the materials needed for the classroom interventions are available online to download at no charge.3

There’s an additional incentive to work on eliminating sexual harassment and gender violence—all schools and universities that receive federal financial assistance are obligated under our civil rights in education laws, in particular Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, to take action against sexual harassment behaviors that limit or erode equal educational opportunity for students.

You have studied bullying, too. Do we know whether the bullying prevention programs now used in many elementary schools help to reduce gender biolence and sexual harassment in middle or high schools?

I know of no such studies that have shown any longitudinal connection—except for research in one area of Australia—that programs on bullying in elementary schools can help to prevent sexual harassment in high school. Most bullying programs are very narrow in scope. They almost never bring up sexual harassment, gender-related violence, sexuality, or homophobia. Unfortunately, too many K-12 schools still fail to distinguish bullying—which is usually defined by state laws that vary greatly state to state—from sexual harassment, which is federally defined and required under federal laws, by the U.S. Department of Education and by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Before we take a closer look at Shifting Boundaries, let’s get some more background. You’ve been working on issues of sexual harassment in schools for decades. How did you get started?

In 1978, the term “sexual harassment” was just becoming recognized as a problem that women were experiencing in the workplace. I was working for the Massachusetts Department of Education in downtown Boston, and elsewhere in the building several high school students were working in the Student Service Center. I learned fourth-hand that one boy in that work space was telling dirty jokes and talking about his alleged or real sexual conquests, and making the girls very uncomfortable and preventing them from being able to concentrate on their work. I called those behaviors “sexual harassment,” but it was puzzling because there was no one among the students who could hire, fire, or promote anyone there. Like most people at this time, my notion of sexual harassment was limited to the workplace. So I wanted to know more—how typical was this? Did other students experience similar behaviors among their peers? I was a graduate student at the time at Harvard, and I said, “Let’s do a survey.” Through the Massachusetts Department of Education, and with my colleagues there and others on our self-anointed “sexual harassment task force,” we were able to survey 200 high school students throughout the state. We learned that this experience of peer sexual harassment was very typical. I then went around Massachusetts talking to approximately 60 students at vocational schools, in particular those in shops and courses where girls were in the minority. In classes like auto mechanics or electricity where there were just one or two girls in the class, the harassment of those girls was extreme, as they were subjected to physical and sexual assaults plus intimidation.

I was convinced that this was mainly a problem in vocational schools until a girl at Brookline High School4 said to me, “Come to our school, too. It goes on here.” Then other colleagues and I started looking at sexual harassment in comprehensive high schools. In 1979 I co-authored our first curriculum on the subject of sexual harassment, Who’s Hurt and Who’s Liable: Sexual Harassment in Massachusetts Schools. (Other editions came out in 1981, 1983, and 1986). However, it’s important to note that it wasn’t until 1999 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that student-to-student sexual harassment was indeed covered under federal law Title IX and that it was the responsibility of the schools to prevent it (Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education).

What does Title IX specify?

Title IX says there can’t be sex discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal financial assistance. The term “sexual harassment” doesn’t appear in the wording of the law. It took lawsuits to extend the notion of sex discrimination to include sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination if it interferes with a student’s right to receive an equal educational opportunity. In 1992, there was a case in the Supreme Court (Franklin v. Gwinnett) involving a 15-year-old girl who had sex three times with her social studies teacher on campus. The teacher was fired. Her case was eventually heard in the Supreme Court over the issue and to determine whether Title IX violations were eligible for compensatory damages. In a 9-0 ruling, the Supreme Court ruled that schools were liable for compensatory damages under federal law Title IX..

That was big news. I appeared on various television programs like “The Today Show” and “Oprah,” as well as with the girl-plaintiff and her lawyer on “Phil Donahue” to talk about the ruling. Universities had been worried about sexual harassment since cases in 1978, and this 1992 case made K-12 schools take notice of sexual harassment, too.

The 1999 Supreme Court decision on student-to-student sexual harassment in the Davis case was terrific and required schools to be concerned and vigilant about peer sexual harassment. But this decision came just one month after the tragic shootings at Columbine High School, which really changed the nature of surveillance and control of students at schools. That’s when states began to pass anti-bullying laws—which, as I’ve noted, share no common definition of bullying.

Finally, in October 2010, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights issued a clarifying memorandum, called a “Dear Colleague Letter,” to U.S. educators saying, in a nutshell, “You can’t call everything bullying when it might be (sexual) harassment and therefore a violation of federal civil rights laws.”

So an effective school curriculum about sexual harassment would be timely. Tell us more about Shifting Boundaries. In the classroom interventions, wWhat are the lessons like?

The lessons are drawn from two curriculum projects I’d done earlier, the first funded by the National Education Association (1994) and the other by the U.S. Department of Education (1999), with some new lessons added. Plus certain lessons needed to be tailored to the laws of the particular state in which we were working. Of course, federal law about sexual harassment applies everywhere, but a few elements in the lessons are nuanced around each state’s own laws—for example, about consent and sexual assault, in which ages and definitions may vary under state laws.

The curriculum is all predicated on the notion of boundaries. Laws are one kind of boundary, and talking about boundaries is a very friendly way of talking about laws. And adolescents understand that in law, age is a major operating boundary—what age you need to be to buy liquor, to drive a car, to vote, to have consensual sex, and so on.

Personal space is another kind of boundary. The classroom lessons talk about this and include exercises helping students to discover each other’s personal space, and hopefully honor it. The educators overseeing the lessons are actively shifting the students’ notions of boundaries and teaching that sexual harassment, which is a civil rights violation, can include violating someone’s personal space.

And we see sexual harassment as a precursor to teen dating violence. Because if you’re allowed to act this way in public, without appropriate interventions from teachers and administrators, what’s to stop you from thinking you can do it in private with a girl/boy, when presumably no adults are around?

What are the school-wide and building interventions like?

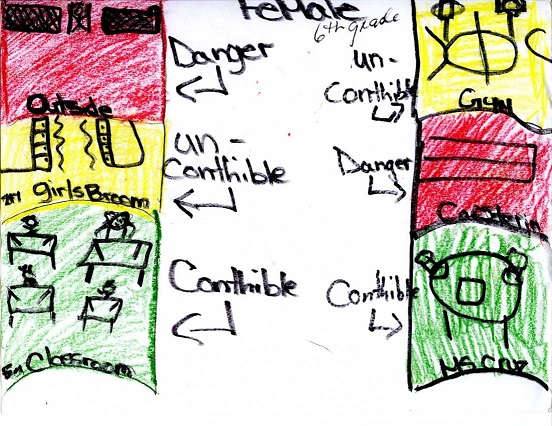

The first intervention is a mapping activity, which the students and adults both love. The teachers hand out sets of colored pencils and copies of a map or blueprint of the school. The students then color in areas of the map—using green for areas on the map where they feel safest, yellow for areas where they feel less safe, and red for where they feel unsafe. The teachers then tally up the results. They may find that girls feel intimidated in different areas than boys, and grade level may make a difference, too. Then school administrators look at these tallied maps and, we hope, make some alterations. They can change flow patterns around the school, change adult supervision in hallways, change which youth are on the stairs or in which halls at what time—there are a lot of modifications that can be made to make students feel safer. This activity draws its inspiration from “hot spot mapping,” which has been used by law enforcement for decades.

The second school-wide intervention, which flows from classroom lessons, is a Respecting Boundaries Agreement—like a restraining order without the force of law. Hopefully, before harassment has escalated, a student can go to a teacher or counselor with the complaint or concern that someone hasn’t been respecting his or her boundaries. The adult then helps the student fill out a form that asks a lot of questions, like “Where did this happen? Did anyone else see it? How can we change this?” Separately, the adult also works with the student who is alleged to have violated the boundaries, to put the Agreement in place. This document needs to be connected to each school’s unique discipline code—it is not a generic form but rather it must be tailored to each school district’s policy and procedures for discipline and remediation.

The third intervention consists of using multiple gigantic, generic, artsy posters about teen dating violence, using real adolescents’ faces.5 These are mounted at key locations throughout the school. At the bottom of each poster, a superimposed sticker says, “If you want to talk more about this, go to see Mr. X in Room 101 or Ms. Y in Room 102.” And that conversation could lead to one of those Respecting Boundaries Agreements.

How prevalent are sexual harassment and gender violence in our schools, and are there differences in the ways girls and boys experience them?

They’re very prevalent, and for both sexes, boys are generally the perpetrators. Girls have many unwanted physical actions perpetrated on to them—whether in so-called “jest” or deliberately—their clothes pulled at, their bras snapped; forced to do something against their will; there’s a lot more sexual aggression from boys toward girls. Boy-to-boy sexual harassment has more to do with not conforming to certain notions of masculinity, and this often turns into gay-baiting and can be very physical and very violent. Both girls and boys are called derogatory gay-baiting kinds of terms. Girls will also get slammed for their reputation—invented or real—for being labeled “promiscuous;” that won’t happen to boys. That’s a big difference. Girls will also malign the sexual reputation of other girls, as well.

Is there evidence of a connection between school-based or teen-dating biolence and domestic violence in adult relationships?

Nobody’s done a study that would show that in a full-scale, longitudinal way. But I’ve said for many years that schools are the training grounds for domestic violence. Years ago, based on lawsuits I was familiar with and on the responses from girl readers of the Seventeen magazine survey we at the then Center for Research on Women did in 1992-1993, I said that some of the girls sounded like “battered women in training.” You’d need to do a really long study to prove such a connection, but I think it rings of common sense. And that’s my point—if you can do this in public, with witnesses and bystanders, what would make you think you can’t do it in private? If students were grabbing body parts and assaulting each other physically when they were dating, then they might well be doing that when they got older, and in less public spaces.

What’s the latest for you and Shifting Boundaries?

In the large, third stage of our study extending from 2011 through 2014, we are working with sixth, seventh, and eighth graders in New York City schools. That will give us a more comprehensive look at the effectiveness of the lessons and interventions as we follow students through these important middle school years. We hope not only that it informs future intervention and prevention programs, but that it truly results in positive outcomes for teens and young adults across the country. Along with countless educators involved with our research, we aim to reduce gender violence and sexual harassment in schools and in young peoples’ lives.

Nan Stein, Ed.D., a senior researcher at the Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW), has directed dozens of national research projects on sexual harassment, gender violence, and bullying in K-12 schools. She addresses these issues in lectures, keynote addresses, and training sessions for school personnel across the country. Stein has also been featured in countless media interviews and has served as an expert witness in multiple lawsuits. Her publications include a book, several school curricula, and many op-ed commentaries, as well as articles in a wide variety of educational and legal journals. She holds a doctorate in education from the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, from which she received an Outstanding Contribution to Education award in 2007.

Learn more about the Shifting Boundaries initiative and research at: www.wcwonline.org/ShiftingBoundaries

1 Stein, N., Sjostrom, L. 1994. Flirting or Hurting? A Teacher's Guide on Student-to-Student Sexual Harassment in Schools (Grades 6 through 12); Sjostrom, L., Stein, N. 1996. Bullyproof: A Teacher's Guide on Teasing and Bullying for Use with Fourth and Fifth Grade Students; Stein, N., Cappello, D. 1999. Gender Violence/Gender Justice: An Interdisciplinary Teaching Guide for Teachers of English, Literature, Social Studies, Psychology, Health, Peer Counseling, and Family and Consumer Sciences (grades 7-12);

2 Bruce Taylor, Ph.D., University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC)

3 Shifting Boundaries: Lessons on Relationships for Students in Middle School. http://www.wcwonline.org/proj/datingviolence/ShiftingBoundaries.pdf

4 Brookline High School is the public, comprehensive high school serving residents in this neighboring town of Boston.

5 Poster messages: 1.) “He pays attention to her.” / “He pays attention to her every move.” 2.) “He thinks of her.” / ”He thinks of her as his property.” 3.) "She takes her out." "She takes it out on her." 4.) “He hits on girls.” / “He hits girls.”