Sari Pekkala Kerr, Ph.D., economist and senior research scientist, testified before the U.S. House Committee on the Budget at a hearing on the benefits of immigration on June 26, 2019. The hearing was recorded and is available from the House Committee on the Budget. Dr. Kerr's full written testimony is below:

Thank you Chairman Yarmuth, Ranking Member Womack, and members of the Committee for inviting me to speak today.

My name is Sari Pekkala Kerr, and I am a Senior Research Scientist at Wellesley College. I received a Ph.D. in economics in 2000, and since then my research has focused on the economics of the labor market, immigration, entrepreneurship, and human capital. I am here in my personal capacity to describe what I think are the most important findings in the field of research related to immigrant entrepreneurs.

The topic of immigration has been studied extensively by economists and other social scientists. Most find immigrants to be a net benefit to the host economy.1 Even large, sudden inflows of migrants have not been found to cause negative employment or wage effects on the natives2, but instead benefit the economy in the long run, with benefits increasing the more highly educated the incoming group of migrants is.3 Similarly, the fiscal impacts of immigration have been found to be positive, and increasing with the skill level of the migrants.4

While the academic literature has been dominated by analyses studying whether immigrants displace native workers in specific labor markets, scholars have spent much less time evaluating the impact of immigrants as founders of new firms and creators of jobs. This distinction is quite important, as the displacement effects studied in the labor markets are likely to be mostly absent in the arena of entrepreneurship. Over the last five years, I have focused my research efforts in trying to understand the role played by immigrants as entrepreneurs in United States, and in today’s testimony I would like to focus on 5 key findings from my own research.

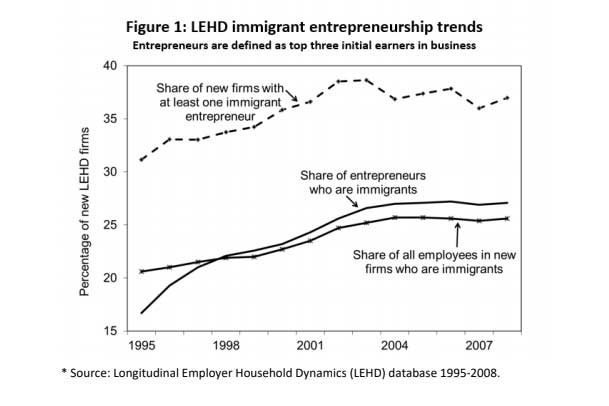

- Immigrants start an increasingly large share of all new employer firms in the United States. Between 1995 and 2012 the share grew from about 16% to 25%.

- The role of immigrant entrepreneurs is equally large (and often more so) in the high-tech sector as it is in “low-tech sectors”.

- There are large differences across US states in terms of the share of businesses owned by immigrants. But in all US states, immigrants start more firms on a per capita basis than natives.

- The job creation share of immigrant entrepreneurs follows closely the firm creation share. Immigrant-owned firms hire slightly fewer employees per firm, but the difference comes from differential location and industry concentration of the firms.

- The jobs created by immigrant entrepreneurs pay somewhat less or provide fewer benefits, largely due their concentration in three key sectors.

Let us now look at each of these key findings in some more detail.

Fact #1: The role of immigrant entrepreneurs is growing

In California, every fourth person you meet was born outside of the United States. But if you step into a gathering of local entrepreneurs, almost half of them will be immigrants. They play an increasingly large role as founders of new firms and creators of jobs.5

Regardless of the source of data used and/or the definition of “entrepreneur” (being it firm owners, firm founders, or self-employed individuals running their own incorporated businesses) there is a clear, increasing trend in the share of firms run by immigrant entrepreneurs. In the 2012 Survey of Business Owners, 26% of recently founded employer firms had at least one owner who was born outside of the United States. That is significantly higher than the share of immigrants in the population (12.9%) or in the overall labor force (16.4%).6 Notably, the growth in immigrant entrepreneurship happens at the same time when the overall rate of business start-ups is falling, further emphasizing the role of immigrant founders in maintaining the dynamics of new firms.7

It is worth noting that many firms (about 1-in-5 of those that have at least one immigrant entrepreneur) are founded and/or owned by a team of individuals consisting of both immigrants and natives. According to many metrics, those firms seem to do better than firms that have either only immigrant or only native founders.

Fact #2: Immigrant entrepreneurs span the whole U.S. economy (and beyond)

Immigrant entrepreneurs are just as visible in the Main Street as they are in internet-based companies. They span anything from the local Chinese restaurant or dry cleaner, to some of the biggest technology companies like Google, Facebook, and Uber.

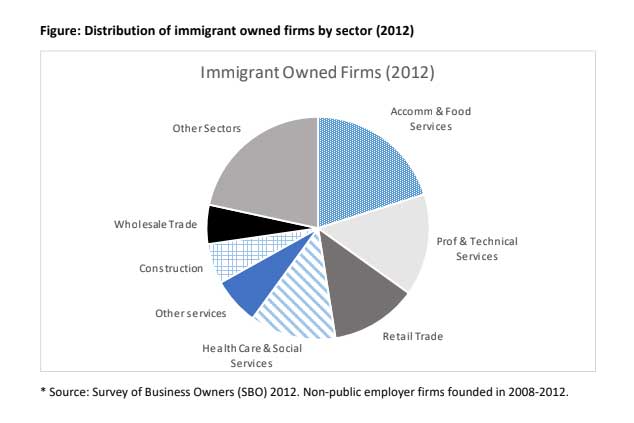

While there has been a lot of discussion around the immigrant founders in the field of high-tech and innovation, immigrant entrepreneurs are just as prevalent in low-tech sectors. They are particularly concentrated in accommodation and food services, professional and technical services, and retail trade, with those 3 sectors accounting for almost half of all immigrant-owned employer firms in 2012. Among recently founded firms, health care and social services also represent a major concentration for the immigrant-owned firms.

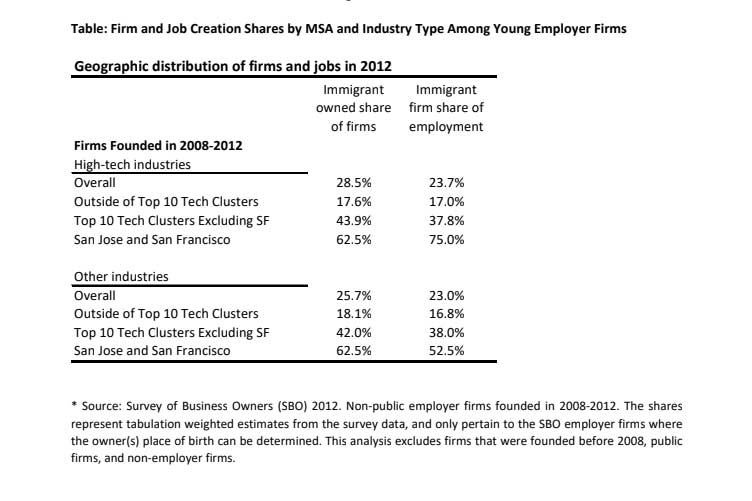

In high-tech industries, 29% of recently founded firms have at least one immigrant owner, whereas the share is 26% in other industries. Likewise, immigrants represent about 25% of all self-employed running an incorporated business. Immigrant-owned firms are also over-represented among exporter firms and are more likely to have operations outside of the United States. These international aspects mean that these firms can benefit from demand well beyond the local market for their goods and services.

Fact #3: Some states are very dependent on immigrant entrepreneurs; others are less so

Some states attract a lot of immigrants. Such immigrant gateway states include California, New York, New Jersey, and Florida where immigrants represent over 20 percent of the total population. Other states have not seen such high levels of immigration, and there are many states where the population share of immigrants is less than 3 percent.

Consequently, there are also vast differences across the U.S. states in terms of the share of firms that have immigrant owners. The least dependent states, such as Montana, the Dakotas, and Idaho, had 6% or less of their new firms founded by immigrants in 2012, whereas the shares for California, New Jersey, and New York exceed 40%. These differences are larger than what would be expected based upon immigrant population shares, and they can be correlated with how immigrant-friendly the policy environments are at the state level.

Yet in all cases the propensity of immigrants to start companies exceeds that of the natives, when measured as the excess share among firm owners above and beyond their population share. For example, while only 2.3 percent of Kentucky’s population was born outside of the United States, almost 9 percent of all newly founded Kentucky employer firms had immigrant owners in 2007. These kinds of patterns are very much expected, as researchers in other countries have similarly found immigrants to be heavily overrepresented among the self-employed and entrepreneurs.

Fact #4: Immigrant-owned firms are major creators of jobs

Immigrant entrepreneurs create job opportunities for U.S. natives as well as for other immigrants. They represent an important source of earnings for many local communities.

Among newly founded firms, first-generation immigrant-owned firms account for 23% of all jobs created by those firms. This is important as young firms account for almost all of the net job growth in America.8 While the young immigrant-owned firms, on average, hire slightly fewer employees (5.0, on average) than native-owned firms (5.9), it is interesting to note that the average number of employees is greatest in those firms that have both immigrant and native owners (7.6).

It is more challenging to provide an employment estimate for immigrant entrepreneurs that would also consider the older public companies, which indeed employ a substantial part of the nation’s workforce.9 Immigrants have played a role in founding many of these large companies, with some estimates suggesting that first- and second-generation immigrants have been a part of the founding team in as many as 44 percent of the Fortune-500 companies.10 Those contributions typically happened many years ago and the ownership is now diffuse, making it hard to incorporate these older firms in the analyses performed above. Regardless, it is safe to say that the overall employment base in America would be much smaller without the contribution of immigrant-owned and –founded businesses.

Fact #5: Differences in job quality come largely from location and sector choices of the firm

News reports have highlighted the polarization of the labor market, with concerns that well-paying mid- level manufacturing and office jobs are eroding. Immigrant entrepreneurs boost demand for labor, but their demand is focused on specific sectors and geographic areas.

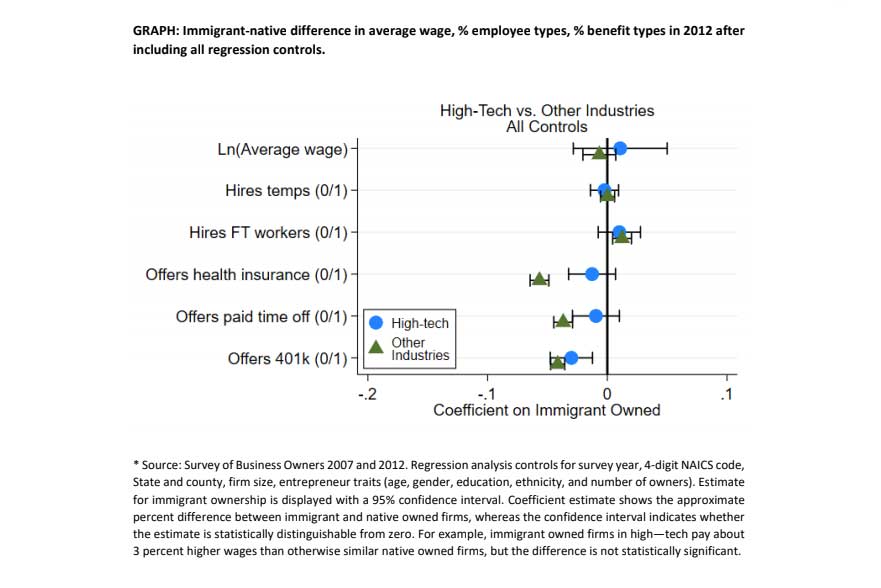

When measuring “job quality” within a firm by the average payroll earnings per employee, the types of employees hired (full-time / temporary), and the provision of fringe benefits (paid time off, health insurance, retirement account / 401-k) it appears that in the “low-tech sectors” immigrant-owned firms pay somewhat lower wages and are less likely to provide employee benefits. Conversely, in the high-tech sectors, immigrant-owned firms actually pay higher wages and offer relatively similar employee benefits as the native-owned firms. If comparing jobs created by immigrant and native entrepreneurs within similarly sized firms in narrowly defined sectors and localities, those quality differences become much smaller. In other words, the concentration of immigrant-owned firms into sectors where the pay is lower and the prevalence of employee benefits is smaller (e.g. service sectors) explains why the average job created by an immigrant entrepreneur looks somewhat different than a job created by a native entrepreneur. When comparing firms that are similar in terms of all observable traits, the jobs created also look more similar.

Conclusion

The contribution of immigrant entrepreneurs to the U.S. economy is significant, but often not fully recognized even among the dedicated immigration scholars. Emerging evidence from other countries suggests similar contributions elsewhere. Perhaps consistent with the empirical evidence is the fact that many countries have created specific visa and policy schemes to attract immigrant entrepreneurs.11 The main U.S. visa program that is specific to entrepreneurs (EB-5) has seen relatively modest use to date, and indeed most immigrant entrepreneurs will have arrived under a variety of circumstances. The current available data do not permit a deeper analysis of immigrant entrepreneurs by visa category or entry circumstance, but existing evidence for college-educated immigrants suggests that the majority of those who wind up starting their own firm that employs at least 10 workers initially arrived with a student visa, a work visa, or as a dependent of a visa holder.12 Similar data are unfortunately not available for individuals without a college degree, who notably represent about a half of the immigrant (and native) entrepreneur population. Additional combination of data from different Federal agencies (including the USCIS) would enable researchers to provide findings that could better support evidence-based policymaking, e.g. in the area of immigration policy.13

Endnotes

- See Kerr and Kerr (2011) for an extensive, international survey of this literature. “Economic Impacts of Immigration: A Survey.” Finnish Economic Papers 24(1).

- E.g. Friedberg (2001) “The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111, Card (2001) “Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration.” Journal of Labor Economics 19, and Pischke and Velling (1997). “Wage and employment effects of immigration to Germany – An analysis based on local labor markets.” Review of Economics and Statistics 79(4).

- E.g. D’Albis, Boubtane, and Coulibaly (2018). “Macroeconomic Evidence suggests that Asylum Seekers are not a "Burden" for Western European Countries.” Science Advances 4(6), and Peri (2014) “Do immigrant workers depress the wages of native workers?” IZA World of Labor 2014: 42.

- Dustman and Frattini (2014). “The fiscal effects of immigration to the UK.” Economic Journal 123, Storesletten (2000). “Sustaining fiscal policy through immigration.” Journal of Political Economy 108, and Borjas (2001) “Does immigration grease the wheels of the labor market?” Brooking Papers on Economic Activity 1/2001.

- The entrepreneurship related numbers cited here come from two sources. Some are based on the Survey of Business Owners (SBO), collected by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2007 and 2012. In particular, the analysis focuses on non-public employer firms where the place of birth of the firm owner(s) can be determined. Immigrant owners are those born outside of the United States. For further details, see Kerr & Kerr (2018) “Immigrant Entrepreneurship in America: Evidence form the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012.” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 24494. The second set of numbers come from the Longitudinal Employer Household Dynamics (LEHD) database that is created by the U.S. Census Bureau and is based on administrative records. Immigrant founders are those who were among the top earners in the firm during its first year of operation. For further details, see Kerr & Kerr (2017) “Immigrant Entrepreneurship.” In Measuring Entrepreneurial Businesses: Current Knowledge and Challenges, NBER Book Series Studies in Income and Wealth.

- The population and labor force numbers are based on the 2010 American Community Survey.

- E.g. Karahan, Pugsley and Sahin (2019). “Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 25874, and Decker, Jarmin, Haltiwanger, and Miranda (2014) "The Role of Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(3). These studies show that the overall business start-up rate has declined since the late 1980s, plummeted during the Great Recession of 2008 and has not recovered since then.

- Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda (2013) “Who Creates Jobs? Small versus Large versus Young.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2).

- Consider, for example, the case of Google with a first-generation immigrant founder (Sergey Brin), or Apple with a second-generation immigrant founder (Steve Jobs).

- https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/new-american-fortune-500-in-2018-the-entrepreneurial- legacy-of-immigrants-and-their-children/

- For example, Australia created a visa for immigrants with entrepreneurial skills in 2012, the UK introduced a new entrepreneur visa in 2008, and Canada also created a similar program in 2013.

- The analysis is based on the 2003 National Survey of College Graduates. Hunt (2011). "Which Immigrants Are Most Innovative and Entrepreneurial? Distinctions by Entry Visa," Journal of Labor Economics 29(3).

- https://www.cep.gov/report/cep-final-report.pdf

June 26, 2019