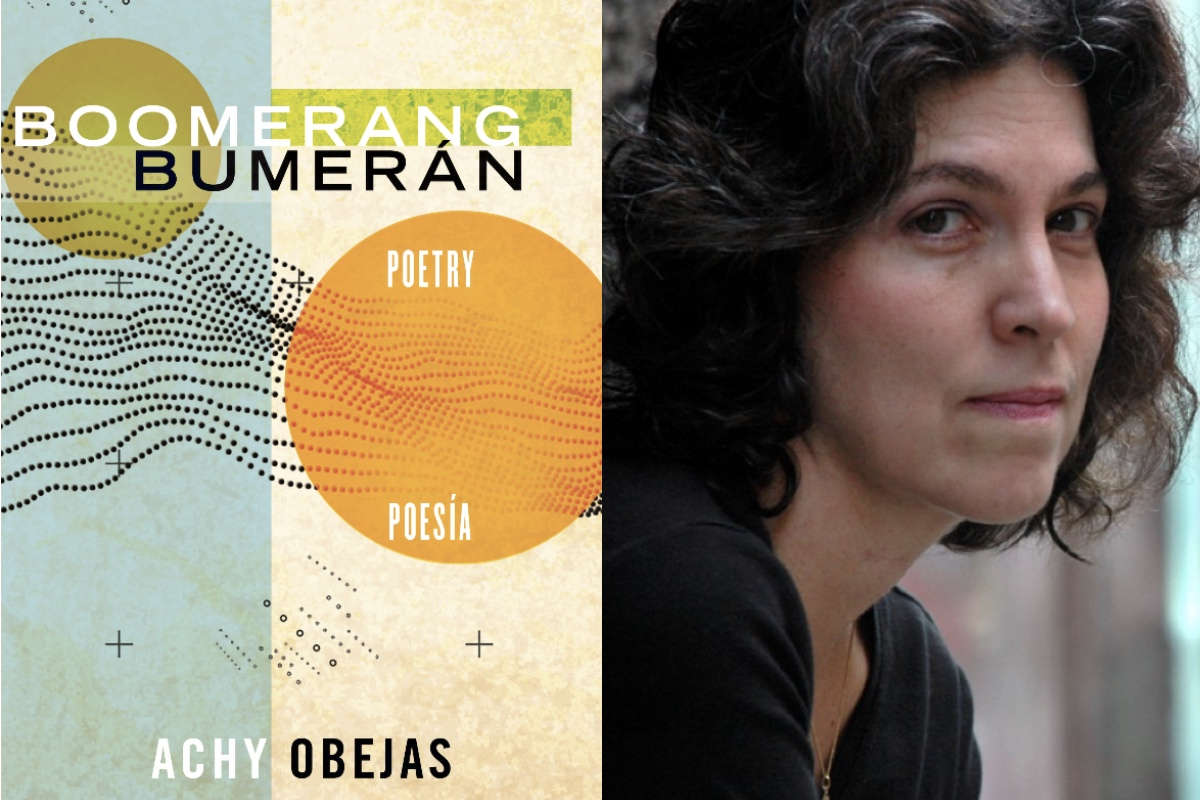

Boomerang / Bumerán By Achy Obejas

Reviewed by Noelle McManus

... Obejas experiments with articles and word-endings to create a semblance of what Spanish may look like in the future.

Estadounidense is the Spanish word for a person from the United States—something like United Statesian. Referring to oneself as americano as a way to convey the English word American is too vague; in Spanish, an American is someone from the Americas. There must be, then, some siblinghood between us, some severed familial connection. But we here in the United States—we amorphous mass of blood and cultures—strip the title from our siblings, try so hard to make it our own that no single word exists to call us what we really are. Estadounidense. The word is concise, genderless, humble.

Estadounidense is the Spanish word for a person from the United States—something like United Statesian. Referring to oneself as americano as a way to convey the English word American is too vague; in Spanish, an American is someone from the Americas. There must be, then, some siblinghood between us, some severed familial connection. But we here in the United States—we amorphous mass of blood and cultures—strip the title from our siblings, try so hard to make it our own that no single word exists to call us what we really are. Estadounidense. The word is concise, genderless, humble.

With Boomerang / Bumerán, celebrated Cubano-Estadounidense poet Achy Obejas digs through English and Spanish language to make sense of this disconnect. She opens the book with an author’s note: “When I began curating, editing, and revising these poems, I realized I wanted to make the text as gender-free as reasonably possible.” Reasonably, here, is a key word; Spanish’s gendering of nouns makes this a formidable task. Obejas notes its difficulty and admits, “So this isn’t a completely gender-free text but is a mostly gender-free text.” Its English half uses singular “they”—a controversy made minuscule in the face of what must be changed in Spanish to provide gender neutrality. In the Spanish half of the book, in which each poem is translated painstakingly (and upside-down, so the reader must flip the book in order to switch languages), Obejas experiments with articles and word-endings to create a semblance of what Spanish may look like in the future. Even the Spanish phrases scattered about the English section test this method: “¡Es une soplo de la vida!” she exclaims in the prose-poem “Volver.” It’s a breath of life! she’s crying, the word for breath gender- neutral, but the word for life, curiously, still feminine.

“Reasonably” gender-free poems may truly be the only ones that can accurately express America (that is, the Americas) in its current state. Obejas, having moved to the US at the age of six, explores immigrant identity and the pain of leaving one’s homeland. “Volver” tells of a guilt-ridden return to Cuba. “We are all weeping because you weren’t here,” she imagines the passersby telling her, “we are wrecked because you weren’t here, how can we have talked about progress without your input ... ?” In another poem, “The President of Coca-Cola,” she uses the image of the late Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta as a stand-in for all Cuban-Americans. Who are the Cubans living in the United States, she wonders? What have they accomplished? Where would this country be without them? Of this Mendieta omni-figure, she writes:

She is the mayor of Wichita, the tender-hearted sibling of the late dictator, a glamorous fashion model, welfare recipient, emergency case in the emergency room, a soldier, dentist and historian, the host of a daily talk show on Telemundo who gulps down a milky Black Cow every day before taking calls.

In Spanish, however, Ana Mendieta is not gendered. Elle, not ella. Le presidente de le Coca-Cola, no one and everyone, “a mother of millions.” This genderlessness is somehow less jarring than the gender neutrality of objects, as in “The Land of Regal Elephants.” Even in the English version Obejas chants, “humo en le torre humo en les altes torres” (smoke in the tower smoke in the high towers). Normally, torre would be el torre, but here it is detached from its nonphysical gender. Le torre in le tierra de elefantes regies—phrases that initially tripped me up, made me reconsider how I perceive inanimate objects through Spanish’s binary lens. Why was I so ready to accept a person without gender but confused by a genderless thing? Obejas drove me to ask myself such questions, to consider the never-ending hypotheses of a language experiment in motion.

But, though the book is mostly genderless, it is not sexless. In “My Island Lover,” Obejas spins a fleshy, visceral image of une amante that can be either male or female, or both. They exist in the way a spirit might, traveling up and down the coast of the titular island (Cuba? the US? someplace else?), living through centuries, and communing with nature. “They have a ninety mile penis / they wield like an oar, / a baton, a staff,” Obejas writes, “to love a boy and / a woman who flew a raft, / a string of rainbow snails on a dead tree.” The subsequent poem, “Inner Core,” imagines sex between a couple as a meeting of two countries: “I kissed you to say sleep with me / and you pulled back the cover of our vast continental expanse, / stubbed your toe on my toe.” Obejas’s lesbian identity is foregrounded in her writing on sex, telling us of the women she sleeps with or watches in public. Desire is human, she insists, as natural as longing for a homeland. Sometimes, the two are intertwined. “I am her lover,” she coos in “The Public Place, After Olga Broumas,” “I am the woman she goes home to, going home.”

Because Boomerang / Bumerán is, at its core, about human connection, it must also be about the societies formed through these connections. Obejas mourns the victims of US-American ego and evil, including in multiple poems about mass shootings. In “The Ravages,” likely inspired by the 2015 Charleston church shooting, she writes,

we can see them in the parking lot

the ambulance, the paramedics

masked too

and shouting in a chorus now

don’t cry, don’t cry!

don’t cry.

Obejas doesn’t shy away from confronting white supremacy, but she still edges carefully past it, prioritizing the voices and stories of its victims. This book is for the people hurting and fighting, not the system that oppresses them. In “The March,” she states this outright, saying, “What we want is an immediate stop to state brutality and the assassination of black people, and native people, and disabled people, and queer people and trans people, and women, and children ...” But, she shrewdly reminds us, protest is not enough; we must also learn the extent of our privilege and work to dismantle the damages caused by our ancestors. As she advises us in “You”: “hold on to the truth of how sometimes your people handled the lash, and sometimes you knotted the witch’s wrist, and sometimes loosed the guillotine and threw the match.”

Despite (or because of) its discussion of painful topics, Boomerang / Bumerán is at its core a book about love. Solidarity with foreign comrades, an intimate touch, calling someone what they want to be called: all are forms that love can take. Though distant from each other, human beings want to be known and understood. What Obejas refers to as “the sea / and the sea and the sea” in “The Man in White” becomes “le mar / y el mar y la mar”—a many-gendered, many-faced expanse spread out between us. We, too, are as vast as the oceans, and the words we call out to each other are attempts at comfort. Colonization has long since painted this land with blood, and Obejas reminds us that it is as vital to grieve with one another as it is to lift each other up. With Boomerang / Bumerán, Obejas wants to open our eyes to the past, remind us what we are. Estadounidenses. Cubanos. Gente de estes continentes hermanes, close enough to touch. As our societies change, so do our languages, and so do the ways in which we are intimate with one another. Obejas marches confidently to the edge of the future. She writes in the poem “Inner Core,” “Sleep with me / I said / swimming against the molten current / just fucking sleep with me.” The desperation and longing in those words ring eerily true in this lonely, aching era.

Noelle McManus is a writer and linguist from Long Island who specializes in Spanish and German. She is a frequent contributor to the Women’s Review of Books.