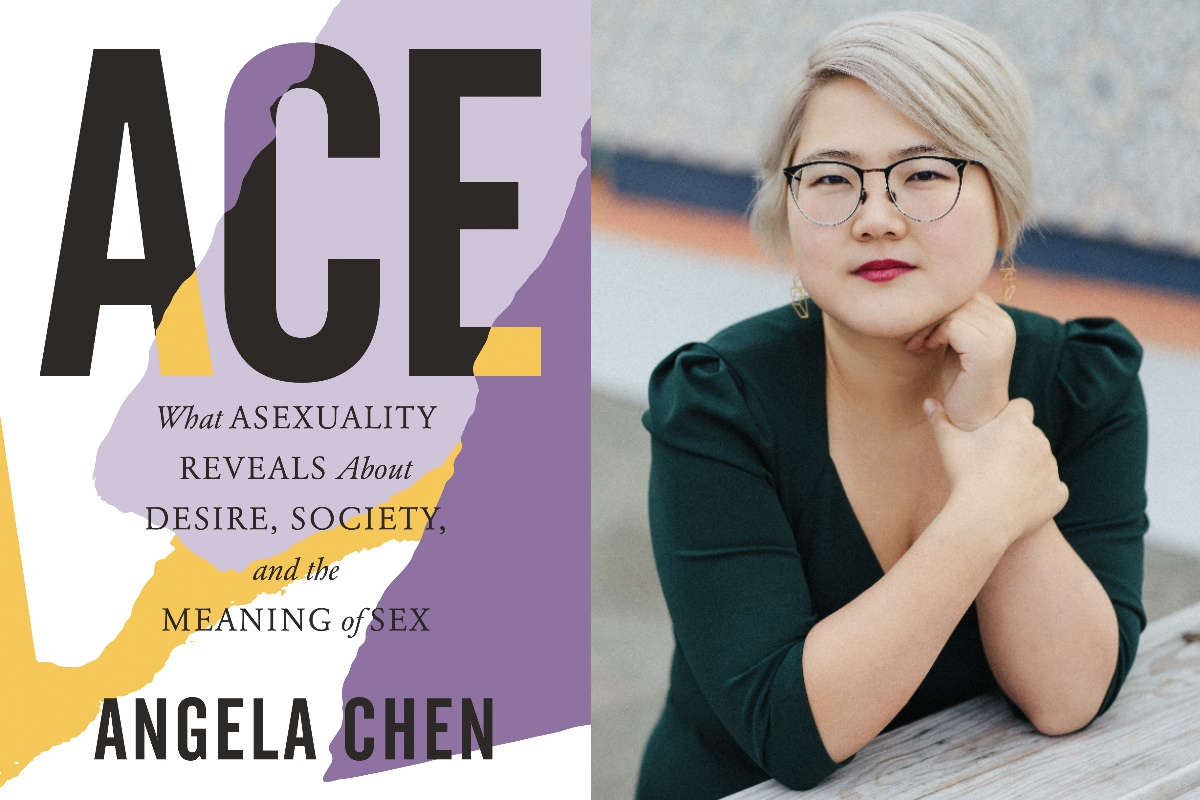

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex By Angela Chen

Reviewed by Ariel Kim

Shondaland has bestowed upon audiences many masterful, binge-worthy episodes of television, from the sharp and unceasing plot twists in Scandal to the heart-stopping drama of Grey’s Anatomy. One of the most memorable lines of the latter, delivered in a quieter, albeit no less emotionally charged moment, is when Cristina Yang says to Meredith Grey, “You’re my person.”

Shondaland has bestowed upon audiences many masterful, binge-worthy episodes of television, from the sharp and unceasing plot twists in Scandal to the heart-stopping drama of Grey’s Anatomy. One of the most memorable lines of the latter, delivered in a quieter, albeit no less emotionally charged moment, is when Cristina Yang says to Meredith Grey, “You’re my person.”

In her latest work, Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex, Angela Chen offers this fictional relationship between two women who occupy “the social space between ‘friend’ and ‘romantic partner’” to convey an example of “queerplatonic partners.” The idea of queerplatonic partners (or QPP) originated in asexual and aromantic communities, as “a way to acknowledge each other’s importance in a way that is rare for relationships that aren’t explicitly romantic, in a society where romance is at the center of how people relate.” Given the rather narrow conception of relationships in the mainstream, as Chen maintains, the “queer” element of QPP is not necessarily about genders or being gay—it is about “queering that social border” and developing “more precise language to fit the range of roles that people can occupy in our lives, roles more varied than the few words available.”

This attention and intention towards language matters, she argues, because language is a form of power, especially considering how the vocabulary of sexuality and attraction often limits our understanding of our own experiences, both sexual and nonsexual. “Intimacy” can seem lewd; “passion” can become sexy; “excitement” can be viewed as indecent, uncomfortable; “pleasure” gets interpreted as “sexual,” as “romance.” And sexual attraction is distinct from sexual drive, separate from sexual behavior, independent from romantic orientation ... but “language traps us into thinking there is only one kind of pleasure and everything else is derivative.”

Chen opens by sharing her own odyssey of ace (or asexual) identity, which began not when she met her first love, Henry, at age twenty-one, but rather when she came across the definition of asexuality online, at age fourteen: “An asexual person is a person who does not experience sexual attraction.” But she did not change how she viewed herself in light of this definition, because she mistakenly conflated “a person who does not experience sexual attraction” with “a person who hates sex.” Since she felt that the idea of sex “held great promise,” she assumed that she was not asexual.

Chen uses her initial misinterpretation of language to highlight a dangerous aspect of asexuality: “it’s just logical enough that people assume they know what it is without doing any further research.” And therefore, on the flip side, “it is possible to be ace and not realize it, to see the word and still shrug and move on,” as she herself did. Misconceptions abound. Despite sexuality’s normative ubiquity within society, in which it is commonly and incorrectly assumed that everyone is allosexual (someone who experiences sexual attraction), Chen asserts that “few people think about sexuality and sexual attraction closely enough.”

Thus, in Ace, she embarks on an interdisciplinary examination of not only asexuality and the ace community, but also the collective obsession (and ignorance) regarding sexuality and desire in general. Part memoir and history, part reporting and research, part cultural analysis and call-to-action, Ace paints a more specific picture of asexuality as “an umbrella that covers different, diverse, and sometimes inconsistent experiences.”

For Chen, it wasn’t until two years after she and Henry had already parted ways that she began to understand her own experience—why the open relationship that Henry had pushed for while he was away at grad school had terrified her. When Chen tried to explain her fear that Henry would have been sexually attracted to someone else and cheated on her, a friend responded that, “it’s often just attraction. Physical. That happens all the time and you manage it ... Almost all the time it’s no big deal. We all learn to deal, you know?”

No, Chen did not know. She had never experienced “just attraction” as a physical impulse. She recounts, “I did not believe Henry when he claimed that wanting sex with others did not have to threaten me. When he talked about how everyone was sexually attracted to everyone else all the time, I could not understand attraction as anything but how I experienced it: emotional yearning—love, really—overpowering and overwhelming ... It sounds illogical now, and like incredible naivete, but for me, desire for love and desire for sex had always been one and the same, an unbreakable link. I had been curious about sex but had never wanted to have sex with any person before Henry.”

At the center of Chen's argument is also the insistence that this is ground for all of us to cover, together, whether we identify as ace or allo or aro or anything at all. Language, Chen argues, betrays all of us “by making sexual attraction the synonym for fulfillment and excitement itself.” When sexual attraction is consistently conflated with other emotions and experiences, constantly confused for other types of attraction and drive and desire, it causes problems of communication for everyone, not just aces.

Chen’s reporting and essays have previously appeared in the Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, The Guardian, the Paris Review, and more. Ace is her first book, and she writes from the intersection of her many identities: Asian, female, twenty-something, ace, New York City-based journalist, mentor, activist. In addition to offering an intimate lens into her own experiences as a member of the ace community, Chen also writes as a participant (and critic) of “mainstream” society, as an individual who continues to listen to and learn about the growing contemporary ace movement.

“Us,” therefore, denotes different perspectives at different moments throughout the book, and although it can become complex, Chen also does not allow us to forget her positionality within this conversation about asexuality’s implications and revelations for society. By counting herself among a more collective “we” in these ways, she emphasizes the multifaceted and intersectional and necessary complexities of thinking about desire.

In a series of succinct, thought-provoking statements, Chen invites us to embrace this complexity, because misconceptions about sexual behavior must be addressed directly if we are to move towards a level of precision that is truly just. “Sexuality is more than sexual orientation.” “Attraction is more than sexual attraction.” “Sexual attraction is not sex drive.” “Intimacy and sex are not the same.” “Touch doesn’t have to be a hierarchy.” She makes these seemingly minute but incredibly purposeful distinctions within the language of sexuality and attraction in order to clarify meaning—the radical sex ed vocab lesson that we didn’t realize we needed.

For example, defining asexuality typically forces individuals to “use the language of ‘lack,’ claiming [to be] legitimate in spite of being deficient.” This is an allo-centric definition, a deficit-based perspective that assigns false value to one, more “normal” experience of sexuality over another. And the culprit, the difficulty, is compulsory sexuality, which permeates societal narratives with the damaging assumption that “every normal person is sexual, that not wanting (socially approved) sex is unnatural.”

Chen, on the other hand, illustrates how sexual attraction across experiences and orientations can be described “via negativa, or explaining what it is not and what a lack of sexual attraction does not prevent us from doing.” It’s a slight shift, but a powerful one. All of the numerous categories of attraction—aesthetic, sexual, romantic, touch, sensual, emotional, intellectual, to name just a few—are distinct, specific, equivalent in connotation. The word asexual becomes value neutral.

But, it is also important to remember that this linguistic analysis is not “just an intellectual exercise.” Definitions alone are not enough to harness the power of language. The word asexual on its own “would be pointless if it only described an experience and did not connect me to people who helped make that experience legible ... the more important reason I identify as ace is because it has been useful for me.” Chen characterizes precision of language as a gift, rather than an obligation: asexuality is “a political label with a practical purpose.”

There are real, pressing implications for both personal and societal growth—unpacking the false hierarchies, dichotomies, and conflations in our language should compel us to also examine our desires with keener eyes. Through her vulnerable and vivid discourse, Chen models this mindful scrutiny—the “I used to think ... Now I think”—that true change necessitates. The goal is a sexually liberated society, in which “context matters, but there will be no sexual act that is inherently liberatory or inherently regressive, no sexual stereotypes of any kind ... We should ask people what they want and not be surprised by the answer.”

Chen herself has done this work of asking people what they want: over the course of writing Ace, she interviewed nearly a hundred people, honoring their stories as key sources of information and insight about asexuality. She reminds us that “tenured scholars are not the only people who produce knowledge or who deserve credit for their expertise.” The everyday and often anonymous activists who, “through intention and trial and error and sometimes pure accident,” built the foundations of the contemporary ace movement were largely facilitated by the proliferation of the internet and search engines and online forums, where people from all walks of life could share experiences, name feelings, and create new language “at a scale and volume that had not been possible before.” Therefore, although asexuality as it is defined today has most certainly existed throughout history, the contemporary ace movement is still relatively young. The ace worlds are growing.

The latter half of Ace focuses on examining the intersections of asexuality with other aspects of identity—feminism and femininity, race, gender, health and ability, relationships, and consent. Chen, in her skillful blend of academic research, detailed reporting, and personal reflection, interrogates all of the assumptions that prevent ace liberation and, by extension, she argues, sexual and romantic liberation for everyone. She tears apart the “political maturity narrative” of sexuality that perpetuates the distorted ideal of a feminist as someone who “has multiple orgasms and multiple partners and wants to abolish ICE.” Sex does not have to be at the center of feminism, and Chen “[does] not have time for those who would say that this calls my feminism into question.” Another false conflation, debunked.

She breaks down the ways in which asexuality is associated with whiteness, how the lack of positive, diverse representation of aces in popular culture reinforces stereotypes and compulsory sexuality. Desiring sex “should not be a requirement of health or humanity,” but the history of pharmaceuticals and eugenics in the United States also suggests otherwise. In the law, too, “romance is required for rights,” and Chen methodically disentangles these threads of sexuality and power and history that have a chokehold on asexual identity expression.

Although Chen does call for structural change and activism in response to the axes of oppression that a critical examination of asexuality highlights, Ace reads as less of a “how to do” manual, and more of a “how to think” guide. Just because “aces can point out contradictions around sexuality and language does not mean we need to solve them or that we are capable of doing so.” The language of attraction overlaps with and implicates the messy and multifaceted language of politics, personhood, privilege ... The work of dismantling pervasive, compulsory sexuality, thus, requires a collective effort. “A life of being understood without any uncomfortable conversations does not exist for anyone.”

Chen acknowledges, too, that “the lack of tidiness” inherent to the language of attraction frustrates her, both in her personal experiences—“the sole hookup of my life had been in pursuit of political growth, not for anything remotely close to pleasure ... [because] what I had called feminism was spite and fear disguised as performance”—and on a societal level, in which sexuality has become a muddled touchstone of identity. It will always be impossible to capture the vast and variable spectrum of sexual experience within a single term or a universally applicable description. Life is rarely so simple. Feelings—emotions, desires, attractions—seldom exist in a vacuum. The impossibility necessitates precision. We must “pay attention to these feelings, their weight and heft and experience, the way they enrich our lives and how each holds their own value” if we are to arrive at true sexual and romantic freedom.

After beginning Ace in the interrogative, Chen ends with the imperative. In her penetrating yet wittily kind voice, she describes many different visions of a sexually liberated society, if we could all just pay closer attention. She both imagines and demands a world through which each individual can move on their own terms, where any expression of orientation or attraction or desire can be as simple—as accepted and acceptable and easy and profound and taken at face value and understood—as “You’re my person.”

Ariel Kim is a graduate student at Harvard University and an English teacher. Her interests include education, social justice, and creative writing.