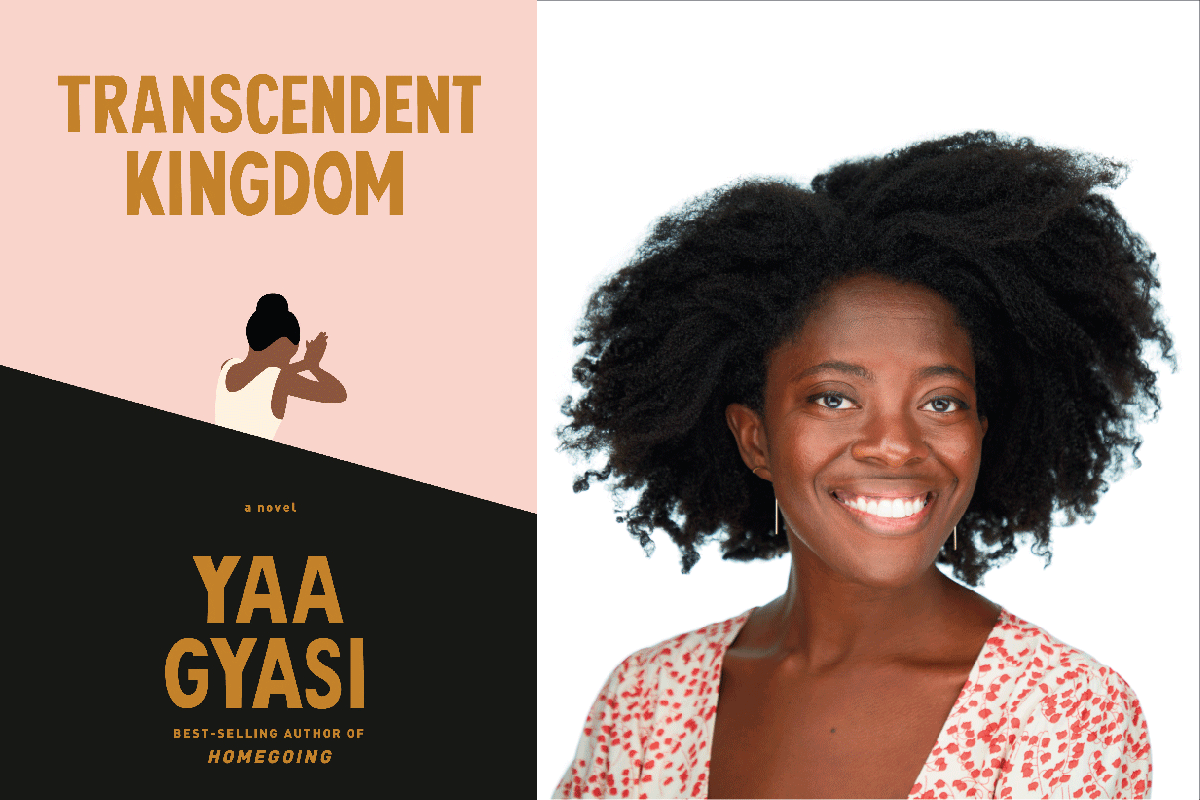

Transcendent Kingdom By Yaa Gyasi

Reviewed by Bridgett M. Davis

How do you make meaning out of the life you find yourself living, with its random senselessness? Can religion help? Can science? Can both?

This is the question both philosophical and literal thrumming throughout Yaa Gyasi’s haunting new novel. Given our current lives amidst a pandemic with an unknowable and unforeseeable outcome, that question of what sustains us makes Gyasi’s novel astute and timely. The story, as taut and intimate as her debut multi-generational novel Homegoing was sprawling and expansive, focuses on one working-class, Ghanaian immigrant family living in Alabama: a mother abandoned by her husband, single-handedly raising her son and daughter. As the story opens, the mother leaves her southern home and comes to live with her adult daughter Gifty in California; once there, the mother lies in bed every day in a recurrence of crippling depression, which manifests as anhedonia, the feeling of nothing. Gifty, a dutiful daughter, tries to help her mother feel something again. This is the front edge of the story: Gifty’s mother’s depression and the question of whether she’ll rebound. Gifty must try to save her mother in between her own responsibilities as a sixth-year PhD candidate in neuroscience at Stanford University’s medical school, where she’s researching “the neural circuits of reward-seeking behavior.” On dates she jokes that her job is, “to get mice hooked on cocaine before taking it away from them.”

That is mostly true. Gifty is trying to understand addiction, and specifically, how the prefrontal cortex enables the brain to suppress addictive impulses. “The mice who can’t stop pushing the lever, even after being shocked dozens of times, are, neurologically, the ones who are most interesting to me,” Gifty tells us.

We understand why: Gifty lost her only sibling, her brother Nana, to an overdose from heroin, an addiction that grew out of a careless doctor’s overprescribing of Oxy-Contin for the teen’s relatively minor basketball injury. Here Gyasi provides a storyline that resonates, given the current epidemic of young Americans dope-sick or dead, thanks to pharmaceuticals and their pushers. Did science fail Nana? Could it have saved him? Can science provide Gifty the answers to understand his death?

Working for hours quietly in her lab, drilling into the heads of mice, Gifty tells us why she studies these lab animals’ brains:

To know that if I could only understand this little organ inside this one tiny mouse, that understanding still wouldn’t speak to the full intricacy of the comparable organ inside my own head. And yet I had to try to understand, to extrapolate from that limited understanding in order to apply it to those of us who made up the species Homo sapiens, the most complex animal, the only animal who believed he had transcended his Kingdom…

This is a novel for the moment in ways Gyasi couldn’t have possibly anticipated. Science is on our minds now, and for many people so is God and His grace. How else to process the massive losses, the many tens of thousands of loved ones in this country who have died alone from the coronavirus—as did Gifty’s brother Nana, helpless against a different yet equally virulent disease? Transcendent Kingdom interrogates the point at which religion and science meet. For Gifty, there is no gulf, as she believes the mice at the heart of her brain experiments nourish her in ways that a faith in God might. She readily admits she has traded the Pentecostalism of her childhood for this new religion, this new quest. Gyasi lays out, in eloquent prose, Gifty’s view on the matter:

The collaboration that the mice and I have going in this lab is, if not holy, then at least sacrosanct. I have never, will never, tell anyone that I sometimes think this way, because I’m aware that the Christians in my life would find it blasphemous and the scientists would find it embarrassing, but the more I do this work the more I believe in a kind of holiness in our connection to everything on Earth. Holy is the mouse. Holy is the grain the mouse eats. Holy is the seed. Holy are we.

Amidst a backdrop of the religion vs. science divide, Transcendent Kingdom is the story of loss. It’s about mourning over a sibling gone, and the ways a familial world shifts on its axis after someone who was once its center, its nucleus, is no more. And ultimately, this is the story of impenetrable grief, and the painstaking and poignant quest to outrun it, wrestle it, find relief from it.

Gyasi powerfully captures Nana’s slide into addiction, and the ways his loved ones grapple helplessly with that descent. Gifty and her mother do not know what to do about Nana’s drug abuse. Her mother screams at him, slaps him, and ultimately sends him to rehab. None of it works. Gyasi ties Nana’s descent to his feelings of abandonment by his and Gifty’s father, whom they call the Chin-Chin Man. Their West African father cannot take the slings and arrows of life as a Black man in this country, and one day leaves his family behind in Alabama, “a punishing state,” and returns to his homeland Ghana, never coming back.

Gyasi shows us how the toxicity of racism converges with personal demons and disappointments. In a scene so brutal in its familiarity it seems taken from one of today’s videos gone viral, a white soccer dad spews racist venom from the stands, directing it at Nana, a gifted athlete. As Nana’s soccer team scores, this angry father screams at his son, “don’t you let them niggers win. Don’t let them score another goal on you, you hear me?” In response, Nana plays the rest of the game “with pure fury. A fury that would come to define and consume him.” Nana’s team wins the game, and Gifty, still a young girl, wonders, “what was that man in danger of losing?” As she narrates the story, looking back, Gifty tells us that was the moment when Nana’s life became a reaction to rather than a free choice. Later, the brother’s rage at their father for abandoning him combusts when Nana realizes across the length of a two-hour bus ride to a soccer game that his father is never coming back to them; Nana stays on that bus, refuses to get off, and vows to never again play the game his father loved.

Racism is never far away from this story, even and perhaps especially where religion is concerned. With a surgeon’s precision, Gyasi slices open the ways racist attitudes overlay and complicate Gifty’s once fervent faith in God vis-à-vis evangelicalism. Gifty recalls how the youth pastor of their church, when pushed by Nana, concedes that even if people in Africa have never heard of Christianity, because they are not “saved,” they will go to Hell when they die. Gifty understands that white religious people equate the poverty of people in other countries with their lack of Christianity, hence white missionaries’ zeal to save them. She notes that these same people hypocritically never question the poverty of white American Christians, and she concludes that her youth pastor believed that the people who deserved Hell were “people who looked like Nana and me.”

Animal activists be warned: The detailed account of the narrator’s experiments on mice are unflinching. “I watched my mice groggily spring back to life, recovering from the anesthesia and woozy from the painkillers,” Gifty tells us matter-of-factly. “I’d injected a virus into the nucleus accumbens and implanted a lens in their brains so that I could see their neurons firing as I ran my experiments.” Of course, this is what medical science is all about, and if we are to have a vaccine for the coronavirus in a near future, it will be because of just such lab work. I admit, however, that my eyes sometimes glazed over the scientific terms that populate the text. As I read the line, “one of the exciting things about optogenetics is that it allows us to target particular neurons, allowing for a greater amount of specificity than DBS,” I didn’t share the narrator’s excitement.

Yet the novel beautifully examines the hardships created by abandonment and displacement, and the attendant shame that comes from both; this motif is conveyed via a vivid Ghanaian-immigrant world, steeped in its own stew of American promise and failure. And so, it’s okay that the novel conveniently gives Gifty a life partner in a courtship that happens off-camera as a tidy plot point. This slim book’s ambitious and compelling interest is in greater relationships than mere romantic ones. In fact, the novel itself is one long meditation on life’s big themes of love and loss, and one woman’s quest to understand the human condition as she grapples with both.

Gifty decides that ultimately both science and religion fail to “fully satisfy in their aim.” So, we go on, Gyasi suggests, understanding all too well that as humans we have not in fact transcended our kingdom. There are things we will never fully know. But we have these pesky, highly evolved brains that convince us we can know, and so we keep seeking answers.

Bridgett M. Davis is the author most recently of the memoir, The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, a 2020 Michigan Notable Book, and named a Best Book of 2019 by Kirkus Reviews, BuzzFeed, NBC News, and Parade Magazine. She is writing the screenplay for the film adaptation of the book, which will be produced by Plan B Entertainment and released by Searchlight Pictures. A Professor of Journalism and the Writing Professions at Baruch College, CUNY, she teaches creative, film, and narrative writing.