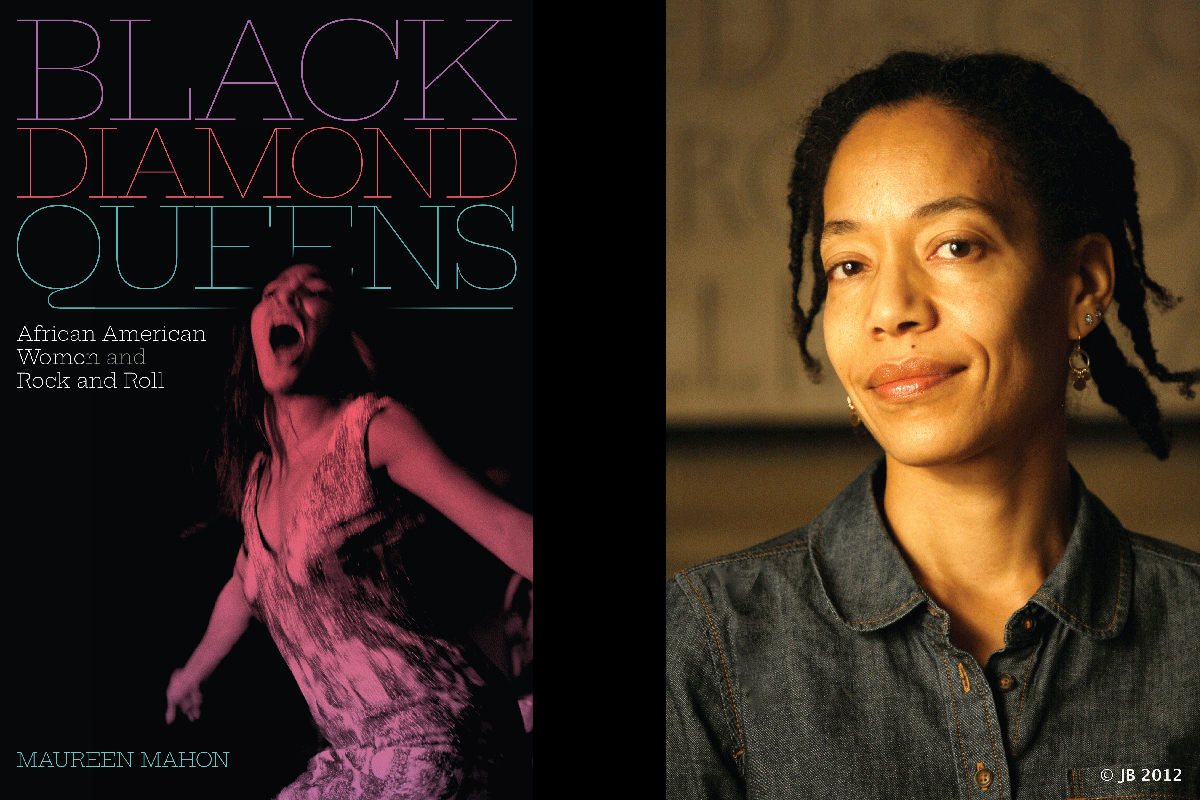

Black Diamond Queens by Maureen Mahon

Reviewed by Briana N. Spivey

When Santi “Santigold” White’s self-titled debut album was released in 2008, the record melded rock, reggae, and ska. Critics loved it—and they also classified it as R&B. White was outraged. She didn’t even like R&B and it most certainly did not describe her music—but reassignment to racially familiar spaces is a common experience for African American women. Cultural anthropologist Maureen Mahon opens her riveting Black Diamond Queens by framing this incident for our understanding of the impact race, gender, and “genre” have on the story of African American women in rock. An eclectic and passionate music fan herself, Mahon describes how “race music” became rhythm and blues and then “rock,” a genre most identified with white men. She quotes, among others, pop music critic and professor Jack Hamilton to assert that “no black-derived musical form in American history has more assiduously moved to erase and blockade black participation than rock music” and then makes a strong case that Black women were expunged most thoroughly.

The general outlines of the story will feel familiar to many, as it did to me. As a Black woman navigating a white and patriarchal society, I know I have to work twice as hard to receive recognition; I feel my responsibility to carry the weight of history and community on my back. Likewise, the Black women musicians Maureen Mahon profiles find their intersectional identities differentially impacted their success in the world of rock and roll. As Mahon writes: “Gendered and racialized assumptions about genre have profound impact on African American women working in rock and roll; they experience a kind of double jeopardy as they navigate terrain in which the body presumed to be appropriate to the genre is white and male.”

Using interviews, recordings, and archival sources, Mahon examines the experiences of artists Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, LaVern Baker, Betty Davis, Tina Turner, The Shirelles, Labelle, and background vocalists such as Merry Clayton, Venetta Fields, Cissy Houston, Gloria Jones, Claudia Lennear, and Darlene Love. There are, of course, other women who have made an impact on rock music, but Mahon chose to focus on a select group whose stories support Black women’s foundational role. Centering these specific experiences also recognizes how rock and roll functions as a mechanism for policing race, gender, and sexuality in the production and circulation—marketing—of popular music.

Mahon sets the stage for our understanding of each of these women by placing them in the time period in which their influence began, beginning with Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. Thornton recorded the original version of “Hound Dog”— her classic dressing down of a no-good man by his exasperated lover. Written for Thornton by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, “Hound Dog” was a hit, raising her profile but yielding no royalties to her. A few years later, Elvis Presley made millions of dollars from his cover. (This, despite the fact that singing it as a man made the cheeky song literally about a dog and his disappointed owner.) Presley never acknowledged Thornton as the originator. In the 1970s, Janis Joplin recorded Thornton’s song “Ball and Chain,” making it a hit. Joplin always credited Thornton as the song writer and for influencing her own unique vocal approach, but while Joplin became a huge star, Thornton struggled for work.

As the discussion of Presley and Joplin’s cooptation make clear, Thornton’s influence wasn’t just through two famous songs; she was responsible for the energy, feel, sound, and attitude that characterized rock music. Mahon’s skill in capturing Thornton’s truth also illuminates the longstanding legacy of Black women’s impact on, and removal from, American music’s origin story. Whether you’re in the Ivory Tower of academia, like myself, or in the arts, as Black women, our contributions are often erased and diminished.

Black Diamond Queens transitions readers forward through time to meet other women, thus ensuring that their stories are portrayed in rock and roll history. A constant theme in Black Diamond Queens is the manner through which genre acts as a barrier for African American women’s success in rock and roll. Some early women in rock chose to incorporate gospel music as the background sound to their vocals, which allowed them to be marginalized as “gospel” rather than rock innovators. Betty Davis, for instance, another woefully overlooked artist, created guitar-heavy, genre-bending rock records in the late 1960s and 1970s. She played amid “giants” like Jimi Hendrix and Carlos Santana, and was a profound influence on her then-husband, Miles, when he was creating Bitches Brew. Despite this, Betty Davis is obscure; the men are household names, recognized as geniuses.

Mahon’s chapter about Tina Turner deviates from the theme of obscurity, as Turner is acknowledged as one of the most important rock vocalists of all time. Turner’s early career in the duo Ike and Tina was a classic rhythm and blues revue, but Mahon writes that her desire to align herself with rock in her post-Ike career was connected to her belief that “maintaining ties to rhythm and blues made neither emotional nor aesthetic sense.

She heard significant differences between the two forms.” As Turner left the abusive husband Ike, she shed other burdens, too. Mahon quotes Turner from a 1984 Rolling Stone feature: “Rhythm and blues is rhythm and it’s blues. And blues is blues—people kinda crooning about the hardships of life. Rock and roll is very up music.” She riffs further on what she sees as the racial caste of rock in a 1991 BBC documentary:

Can you imagine me standing out and singing about cheating on your wife or your husband to those kids? Those kids can’t relate to that. They’re naughty. They want to hear some fun things. Rock and roll is fun. It’s full of energy, it’s laughter. It’s naughty. To me, a lot of rhythm and blues songs are depressing. They are, because it’s a culture you’re writing about and a way of life. Rock and roll is white, basically, ‘cause white people haven’t had that much of a problem so they write about much lighter things and funnier things.

Turner is one of a few of the Black women represented in the book who saw their impact on future generations and who made a lot of money; most did not. Therefore, I would recommend this book as a correction to the record, so to speak. If you are curious about music and its development across genres or would like more examples of Black women’s exquisite impact on every aspect of life, Black Diamond Queens is for you. You won’t find many of these queens on the walls of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame or in canonical texts discussing the origins of rock and roll. Still, crucially and inspiringly, you might see yourself in this group of Black women whose manicured fingers are all over rock and roll. At the very least, you will be exposed to some incredible new songs.

Briana Spivey is a graduate student in the clinical psychology doctoral program at the University of Georgia. Briana’s research interests are focused on understanding the implications of cultural coping constructs, such as the Strong Black Womanhood (SBW) schema, on the mental health of African American women. Along with this research, Briana is also interested in the development and implementation of culturally adapted psychological interventions for African Americans. Check out Briana's "Black Diamond Queens" playlist on the WRB website.