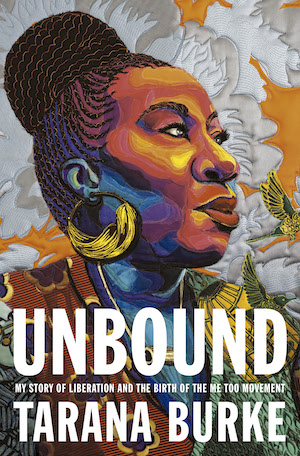

Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement By Tarana Burke

Reviewed by Ariel Kim

In October of 2017, the hashtag #metoo went viral overnight, in light of reporting on sexual abuse cases that were surfacing throughout Hollywood. The Me Too Movement, which Tarana Burke had launched over a decade earlier, quickly broke into the mainstream vernacular in a way that forced everyone to confront the prevalence of sexual abuse. But when Burke woke up on “that Sunday morning in the fall of 2017” after a night out with friends, awash in “the sheer number of people boldly saying #metoo online,” she did not feel thrilled or energized or even legitimized.

In October of 2017, the hashtag #metoo went viral overnight, in light of reporting on sexual abuse cases that were surfacing throughout Hollywood. The Me Too Movement, which Tarana Burke had launched over a decade earlier, quickly broke into the mainstream vernacular in a way that forced everyone to confront the prevalence of sexual abuse. But when Burke woke up on “that Sunday morning in the fall of 2017” after a night out with friends, awash in “the sheer number of people boldly saying #metoo online,” she did not feel thrilled or energized or even legitimized.

Instead, she felt distressed, dejected, and terrified. Burke opens her new memoir, Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement, with a detailed description of this emotional turmoil. She was alarmed “at the thought of inviting people to open up and share their experience with sexual violence online without a way to help them process it.” As she had learned the hard way in her early years as an organizer, “it is wildly irresponsible to make people feel comfortable enough to open up without being prepared with the resources to help them process their experiences and receive continued support.” On a more personal level, in addition to her mounting exhaustion from “trying in vain to amplify [Me Too] for years, with zero resources and little support,” she was now going to have to “fight a viral hashtag that probably wouldn’t be connected to the origins of the work at all.” She feared that everything she had worked toward in her career as an activist and an advocate for exercising empathy to oppose sexual violence would be co-opted, because “they will never believe that a Black woman in her forties from the Bronx has been building a movement for the same purposes, using those exact words, for years now.”

And so, in the wake of #metoo going viral, she called her close friends as well as her child, to vent and troubleshoot and ask them how to navigate the trends and threads on Twitter; she sobbed; she scrolled; she read. And as she read, she realized that, although she had just spent a turbulent twenty-four hours “wringing my hands and pulling my hair out trying to figure out how to save ‘my work’ ... my work was happening right in front of me.” Rather than getting caught up in proving that she had “conducted enough workshops, participated in enough panels, and given out enough t-shirts and stickers to earn the right to say that the work, and the phrase that encapsulated it, was mine,” she was determined to lean into the shared work of this movement with renewed fire. Not because she wanted recognition or because she needed the platform, but because she is “hardwired to respond to injustice.” Burke, in this pivotal moment, reinvented her activism to encompass “all the folks who were using the #metoo hashtag.” The outpouring of survivors’ voices made it clear that the work of uplifting empathy and introducing healing with the burgeoning Me Too Movement was far from done.

Unbound, however, is not the story of what came next—of her ceaseless social justice work, of being named TIME’s 2017 Person of the Year alongside other “silence breakers,” of how the reverberations of “Me Too” continue to shake society today. Unbound is, instead, Tarana Burke’s story of “how we got to those two simple yet infinitely powerful words.” It is her story of what came before, of healing and liberation.

Before there was Me Too, before there was Twitter or news feeds or the definitions and context with which to understand language like rape and molestation, there was ... unkindness. There was a young Black girl, raised in the Bronx, who wrestled and wreaked and lived within and drowned beneath and eventually emerged victorious against that unkindness. “Unkindness is a serial killer,” and there were many versions of a young Tarana Burke who, at each stage of her life, reinvented herself against the backdrop of this emotional destruction, before she realized liberation.

Burke narrates this journey to healing so that each chapter—although they do build upon each other—can stand alone as its own meditation on a subject or an emotion or a focal moment. She takes the time to center each of the many versions of herself in their iteration of a present truth. She infuses her story with reflections in retrospect, and within the present of that given moment with the emotions and the capacity of the person who she was at that part of her life—the seven-year-old survivor of sexual assault, the high school student getting into fights, the recent college graduate determined to organize change, the unanticipated single mother.

The result is that her voice as an activist now, post-Me Too, sounds no more or less fierce than any of her other voices, and it is clear that she holds each of these multitudes, these truths, within her still. During each reinvention, she “didn’t have to start from scratch. I just had to dust myself off, because the best parts were already there.” She is the adolescent who read Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and felt like the suffocating secrets that she had been holding within herself for years were finally seen. She is the teenager who listened to a recording of Angelou reading “Phenomenal Woman” in her Honors English class and realized that the same body that could hold pain and anger could also hold joy and beauty. These nascent selves of Burke’s past are also essential components of her present.

Since hers is an emotional journey, the events are not always recalled chronologically; healing requires practice and will not always be linear. She is, thus, a master of pacing. Whether we are entrenched in the details of her first horrible and bewildering visit to the gynecologist or we are tracing her evolving relationship with Catholicism as she moves between different primary and secondary schools, the story never drags.

Instead, the emotional present of each moment wells from the page. When she describes her reactions to the Central Park Jogger case and the murder of Yusef Hawkins, she reflects on how, “I didn’t empathize with the jogger as a rape survivor at the time—I connected with the young Black and Brown boys whose lives were being snuffed out simply because their Black and Brown skin made them expendable.” As a new organizer, she had not yet been forced to confront the reality of her abuse—that came later, when a young girl named Heaven came forward with her own story of sexual violence, and Burke sent her away instead of listening, unable to “meet her at the apex of her courage” and even say “me too.” But, even before this turning point, “standing and fighting against the diminishment and destruction of Black bodies had become a proxy for the diminishment and destruction of my own Black body.” She cultivates this passion for organizing against injustice throughout high school and at Alabama State University—“yet another chance at [the] reinvention” that she craved—where she organized a protest on campus in response to the Rodney King trial by cutting her black headwrap into strips and handing them out for demonstrators to tie around their arms. After college, she moved to Selma, Alabama, to continue community-based activism and eventually founded the nonprofit Just Be, to support Black and Brown girls between the ages of twelve and eighteen. The day before she found out she was pregnant, she was arrested for cursing out city council members at a meeting to vote on appointment powers. She posted bail, then bounced between the law office, the National Voting Rights Museum, and the grocery store in the afternoon: But that was “my life in Selma,” she writes, “I was always ripping and running around town. That was the work. I was used to it.

Unbound is ... Tarana Burke's story of 'how we got to those two simple yet infinitely powerful words.'

And yet, although her work as a community organizer “allowed me the space to channel my rage and hide my shame,” her passion and success only “took me further from the negative parts of my life and recast me as a person who wouldn’t have to deal with such things.” As she realized in the face of her inability—ultimately, unfortunately, hauntingly—to help Heaven, this was a precarious order, built upon reinvention after self-reinvention that failed “to stare down the monster that is sexual violence and call it out by name.” The complex “culture of secrecy and silence” around the cycle of sexual violence that disproportionately impacts the Black community is shaped by a history of false accusations and police brutality, of systemic racism and poverty. It is a “trap in which so many Black girls find themselves, either performing our pain or performing through it.... We didn’t get the air to be reborn and handled warmly.”

So, on the pages of Unbound, she gives herself the air to be reborn, handles each version of herself warmly. Burke closes the acknowledgements of her memoir by writing, “I hope to have a long life with multiple versions of myself, but I will never run out of things to be as long as I am grateful.” She is grateful and proud and loving and celebratory and funny. She speaks deep wisdom plainly and easily. She doesn’t mince words or try to make excuses. In the wake of #metoo, she began to realize that, alongside all of the other sexual violence survivors who she was committed to helping, she herself was not undeserving of “empathy for that dark place of shame where we keep our stories.” Burke admits, “I still didn’t have the resources I needed to help, but unlike all those years ago with Heaven, I was empowered to try ... Even if I had work to do in my understanding that I wasn’t a receptacle for harm ... I had to start thinking of myself as worthy if for no other reason than to not fail these babies—the way I had allowed myself to fail Heaven.” In the true spirit of activism, she is reflective and raw in the service of growth, both personal and collective. Burke’s honesty reinforces #metoo as the work of a movement, not just a moment.

Besides, as Burke contends, “what is the point of a movement for liberation if we can’t reflect the same dignity and accountability between each other that we are demanding from people outside of our communities?” I am reminded of the work of another activist, adrienne maree brown, who writes, “How do I hold a systemic analysis and approach when each system I am critical of is peopled, in part, by the same flawed and complex individuals that I love?”

Burke lives and writes the answer by holding all of her selves to the same standard of dignity and accountability, modeling fierce love. Unbound portrays the complex dynamics of dismantling the harm done by sexual violence: shame and fear are mixed up with care and support; empathy is the work of a community composed of individuals, each on their own journey to healing. At the end of each chapter, I was convinced that Burke had reached absolute wisdom. But with each ensuing chapter she continues to develop her perspective and process her experiences so as to encompass more—more reflection, more healing, more exhaustion and energy and kindness. Growth is a journey for Burke, not a final destination. Unbound tells the story of an important milestone along the way: liberation from that serial killer, unkindness, and the birth of radical empathy. Because this movement is not just a viral hashtag #metoo, but also a vital step towards justice.

Ariel Kim is a graduate student at Harvard University and an English teacher. Her interests include education, social justice, and creative writing. She reviewed Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex in the September/October issue of the Women’s Review of Books.