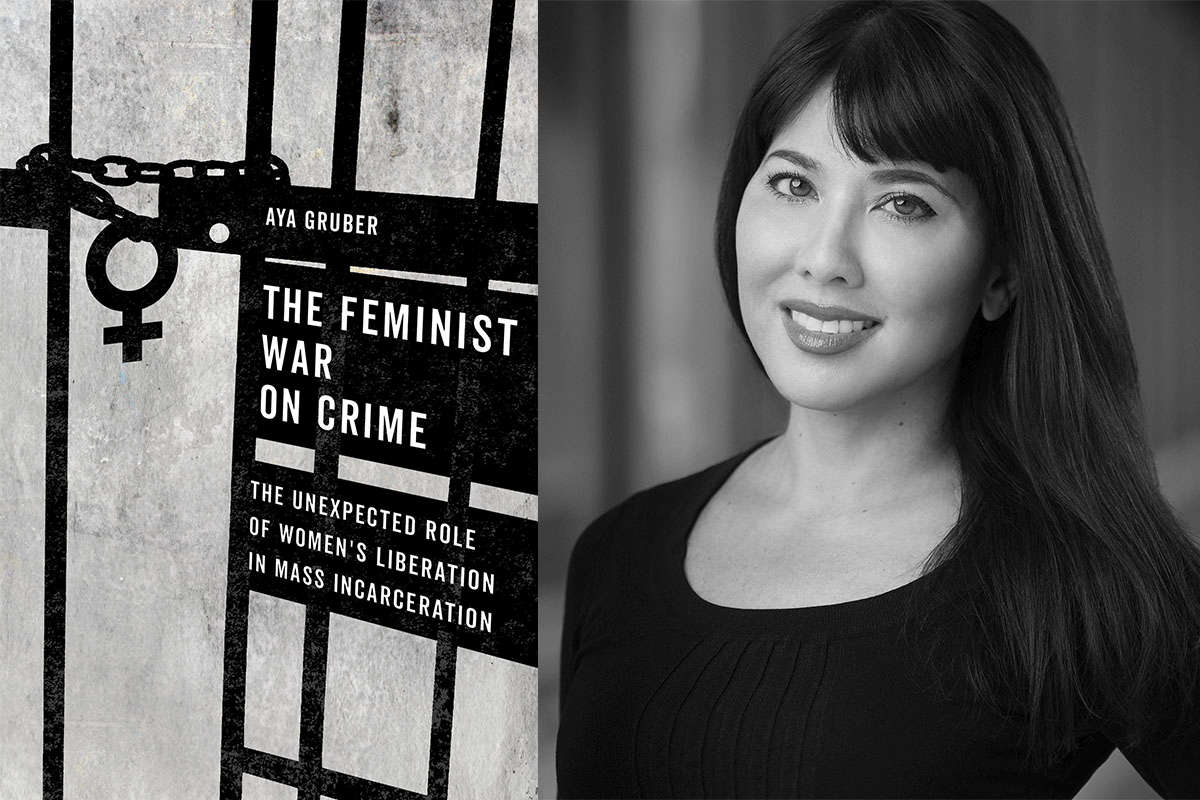

The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration By Aya Gruber

Reviewed by Charis Caputo

As soon as the #MeToo movement began, so too the backlash. The accused parties were predictably defensive, the stories and tropes familiar: a series of powerful men and conservative pundits, beginning with Woody Allen, invoked the “witch hunt” metaphor; during Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing, Trump declared it a “very scary time for young men in America.” But the backlash is not just partisan, nor is it purely patriarchal. Some second-wave feminists have decried a growing generation gap in the larger movement. In 2018, critics like Masha Gessen and Daphne Merkin lamented the “misplaced scale” and “victimology paradigm” of increasingly sex-negative activism that labels every awkward encounter “predatory.” Meanwhile, the feminist party line arguably remains that #MeToo has not gone far enough, as second-wave lawyer Catharine MacKinnon puts it, to shift “gender hierarchy’s tectonic plates.” A fear of retrogression means that attempts to differentiate the severity of various instances of sexual misconduct, or the credibility of allegations, are often maligned as defenses of a persistent rape culture, and many feminists continue to champion harsh punishment of abusers both inside and outside of the legal system.

Into this contentious terrain wades legal scholar and former public defender Aya Gruber, a self-described “feminist, woman of color, defense attorney, and survivor,” to draw our attention to a social justice issue that, while incredibly timely, is widely overlooked in a popular commentary so focused on the reputations of privileged and high-profile men: the relationship between sexual violence activism and mass incarceration. The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration asks how, in this epoch defined by both #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, do we square the punitive streak in contemporary feminist discourse with the emerging liberal consensus against mass incarceration? How do we explain the paradoxical reality that, “today, those most vocal about prison reform are also often the most punitive about gendered offenses, even minor ones?” To answer this question, Gruber excavates more than 150 years of feminism’s internal contradictions as related to American jurisprudence, tracing the ways in which the dominant wings of movements against gendered violence have allied with existing structures of punishment, in the process helping to strengthen those structures which disproportionately punish the economically and racially marginalized. Her study shows us that punitive feminism is not endemic to the current generation, that Millennials and #MeToo are inheritors of a long, contradictory, and often implicitly (or explicitly) racist history of attitudes toward sex, violence, and criminal justice.

Gruber’s historical narrative progresses chronologically and begins with first-wave efforts to fight rape and domestic violence in the later nineteenth century. Despite a socialist-feminist streak in first-wave thought, “Middle-class Christian sensibilities rose to the top,” and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union became the preeminent feminist activist organization by the end of the century, a group “committed to eradicating the vices of sex and alcohol” through “criminal regulation of drunkenness and lust.” Many social historians have convincingly situated first-wave feminism within the larger context of reform movements aimed at bourgeois social control of laboring and ethnic bodies. And acknowledgement of the racist rhetoric and strategies of prominent first-wave figures has become an important part of feminist soul-searching in recent years. In this vein, Gruber shows how first-wave legislative victories disproportionately punished poor and Black men. Prohibition, which middle-class white feminists argued was a prophylactic against domestic abuse, targeted the ethnic working classes. Age-of-consent legislation and anti-prostitution measures such as the Mann Act and the feminist movement against “white slavery” intersected with the Reconstruction-era discourse of Black men as a threat to white female purity—used in the South to justify epidemic levels of lynching and racial retrenchment. Thus, laws undertaken to address rape and exploitation became a legal tool for the targeting of Black men. In 1812, for instance, the Black boxer Jack Johnson was prosecuted under the Mann Act for transporting his own white fiancée across state lines.

More surprising is the symbiotic relationship that Gruber discerns between second-wave feminism and the War on Crime. Little feminist action took place in the criminal arena between the Progressive Era and the antirape and battered women’s movements that emerged in the early 1970s. These latter movements were originally antiauthoritarian and non-carceral in nature, trading in the anti-police, anti-violence, anti-state discourse of the Vietnam era. Even as Nixon and the Silent Majority went hard on crime, the discourse of the early second wave included the voices of ad hoc shelter organizers, feminists of color who advocated social welfare programs over punitive legislation, and liberal antipatriarchy feminists who pushed for socioeconomic reform as well as liberation from oppressive domestic norms. But these sub-movements, Gruber argues, were soon eclipsed by the ultimately triumphant “legal feminist” wing: civil rights lawyers and victims’ advocates who saw domestic violence as a failure of criminal law.

Indeed, at the time, most domestic violence complaints did not lead to arrest or prosecution. Legal feminists attributed this non-punitive approach to the inherent sexism of law enforcement and to a legal system that tolerated wife-beating as a patriarchal norm. They saw this status quo as a continuous jurisprudential line going all the way back to the early-modern principle of “chastisement”: a husband’s right to correct his wife through force. Gruber demonstrates that the history of domestic violence legislation and attitudes in the US is actually much more complex; states have often advocated harsh punishments for perpetrators, thought to be “unmanly drunkards.” Southern states have a particularly pronounced history of instituting corporal punishment for domestic violence, often labeled a “negro crime.” In the 1970s, the logic favoring non-arrest of domestic abusers was complex. As both sociologists and law enforcement attest, more often than not, victims do not want their partners arrested or prosecuted, either because of affection, fear of retribution, financial dependence, or some combination of all three. But legal feminists in the 1970s and 1980s framed their efforts towards arrest and prosecution as an overturning of a patriarchal system designed to protect dangerous male criminals. In their narrative, according to Gruber, “violent male police officers using violent arrest to control violent men was not a pathology of a ‘fascist’ state. It was feminist.”

A great deal of recent scholarship and political discourse—on both sides of the aisle—has reevaluated the American turn towards crime control over social welfare in the seventies, eighties, and nineties, a paradigm shift which is now almost universally acknowledged to be the origin of this country’s current carceral crisis. Gruber points out that feminist movements against gendered violence are implicated in this shift. In the era of the Moynihan Report and mandatory minimum sentencing, legal feminists fought for—and won—mandatory arrest and no-drop prosecution of domestic violence offenders, often ignoring sociological evidence that criminal intervention inflames violent dynamics within families, targets marginal groups, and leaves women economically vulnerable. In so doing, feminists “shored up the coercive arrest model of policing,” and “the battered women’s movement’s carceral turn influenced the larger American carceral turn, even as it was influenced by it.”

Gruber argues that, in the eighties and nineties, feminism’s dominant carceral streak then intersected with the victim’s rights movement, an outgrowth of the War on Crime that advocated “swift and aggressive prosecution and easily obtained convictions unobstructed by procedural protections for defendants.” Legal feminists aligned with this movement to reform state laws that recognized rape only if accompanied by evidence of violent struggle and to ban the practice of entering a victim’s previous sexual history into evidence. At the same time, they worked to expand the definition of rape. In a post-sexual-revolution world, women could freely engage in sex outside of marriage, which made them vulnerable in new ways. While sex-positive feminists saw liberated sexuality as a source of power, others like Catharine MacKinnon warned that sexuality continued to be “the primary social sphere of male power” and called on the fist of the state to “topple male sexual dominion.” By the 1980s and ’90s, activists had successfully expanded the definition of “coercion” to include any act outside of the framework of enthusiastic consent. Thus, although women remain vulnerable to sexual violence, although rape culture and attitudes of “victim blaming” surely persist, both the criteria and punishment for rape were significantly expanded under the law.

The consequent prosecutorial reforms have meant that, “since the 1980s, the population of sex offenders in prison has exploded,” Gruber writes, even as the number of reported rapes has declined. Some feminists might tout this development as a victory, but it is one increasingly at odds with liberal and progressive priorities. Furthermore, in order to toe the line, Gruber argues that feminists—not just prosecutors, but activists in general—are forced to paint all assault victims as morally pure and irrevocably traumatized, and to support black-and-white arguments. “No always means no” and “victims should always be believed,” regardless of context or nuance, is the kind of rigid, punitive logic that #MeToo’s detractors bemoan.

Catharine MacKinnon, feminist legal scholar, activist, and author.

That latter phenomenon has often been explained, understandably, as an outpouring of long-suppressed female rage. We think of this as an unprecedented moment, a necessary corrective. And in a world where the stakes of feminist consciousness-raising feel so high, where Kavanaugh was confirmed, where the president brags about grabbing women by the pussy and his challenger has faced allegations of sexual assault, where, according to the Office for National Statistics, the majority of victims still don’t report their assaults, this kind of feminist self-criticism can feel risky, even repressive. When Gruber makes statements like “‘no’ ... sometimes means ‘yes’” (as evidenced by college students who self-report engaging in “token resistance”), it’s hard not to feel angry. For those of us who have said no and meant no and had our no’s overridden, and often not even reported it, this book sometimes seems to engage in a kind of fallacy of misplaced concreteness; it tries to quantify what can’t be quantified: trauma, desire, violation.

And yet, this is the beautiful and often perplexing tension inherent perhaps in all feminisms: how do we draw connections between seeking justice in our interior and intimate lives with seeking justice in the world at large? Gruber makes a compelling case for #MeToo as a movement continuous with earlier, influential feminisms which have participated in and contributed to racial disparity and incarceration. She does so not as a screed against feminists, but as a way of showing us how we “can do better.” She concludes the book by outlining a “neofeminist” approach that views sexual misconduct and battering as “pressing social problems that reflect and reinforce women’s subordination,” while also approaching criminal law as a last resort.

The release of this book in the summer of 2020 was almost preternaturally timely. As I marched in the streets of Brooklyn calling for the defunding of NYPD, I thought often about the future of punitive feminism, what it would mean to live as a (white) woman in a world without a professional police force. We are certainly now at a cultural crossroads at which we can and must reckon with the carceral history of feminism, and Gruber advances that reckoning substantially.

I don’t think this is a perfect book. At times it seems to conflate anti-domestic violence and anti-rape activism in ways that weaken and confuse the narrative. I think it overstates the causative influence of legal feminism on the War on Crime, which was already overdetermined by the time feminism leaned punitive. It argues against a linear-progressive understanding of societal intolerance of gendered violence, while failing to fully account for the ways in which shifting social dynamics like urbanization, secularization, and sexual liberation have required new forms of sexual regulation. But this is overall a subtle and well-researched work of legal and feminist scholarship. It acknowledges that feminism—indeed all ideologies, all women, all intimate relationships—contain contradictions. We often fear these contradictions, and understandably so: patriarchy is always eager to use them against us. But to acknowledge them can be a sign not of retrogression but of ideological strength, and, right now, we need to be strong.

Charis Caputo is an editorial assistant for Women’s Review of Books and an MFA candidate in Fiction at NYU. She holds an MA in History from Loyola University Chicago.