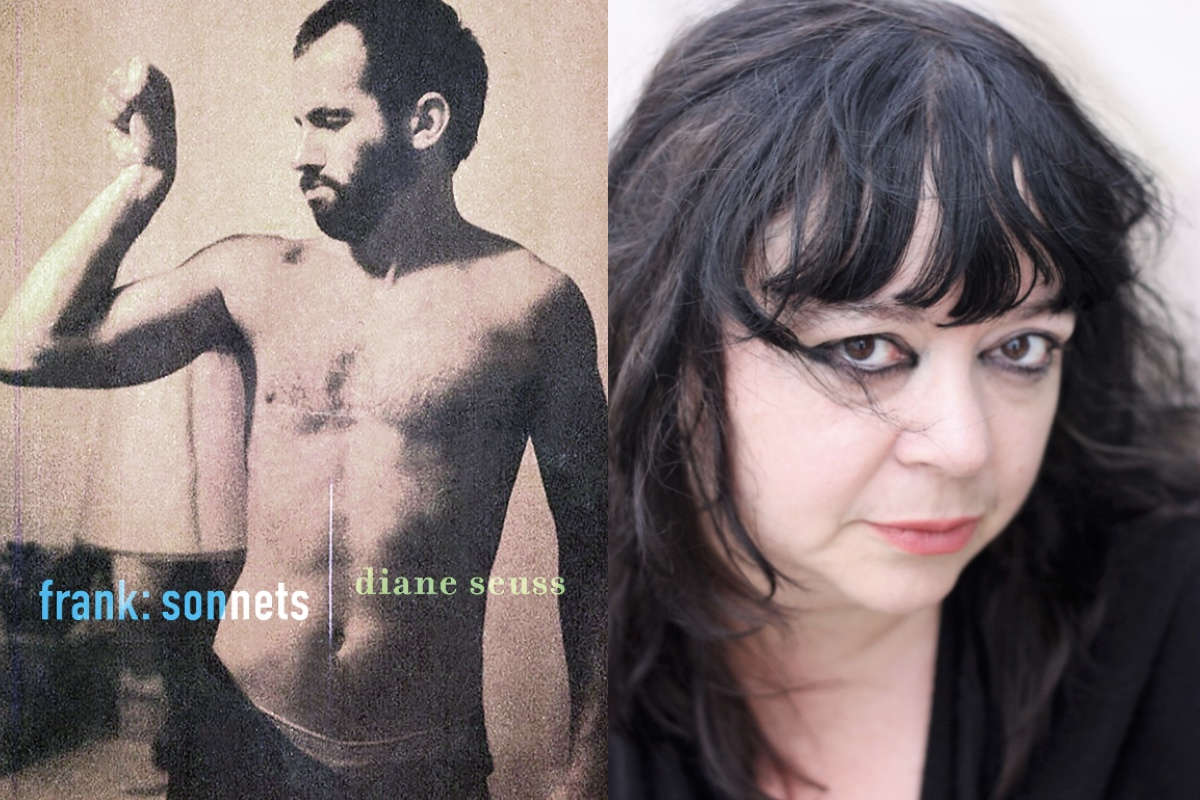

frank: sonnets By Diane Seuss

Reviewed by Laurie Stone

The established literary world doesn’t stir what she writes.

In a minute I’m going to shut up and let you hear Diane Seuss. The thing I love about this book and all her books is that reading her is like being in a conversation with her except she’s doing all the talking, and you are listening to a person who would just as soon be talking to herself. Why are there only sonnets here—128 to be precise? Why do you decide to walk in a blizzard? Why do you see how far you can swim underwater on one breath? A sonnet is like a trapped body: all physical limits and nowhere to run but inside the lyrical imagination. Fourteen lines, again and again. Remind you of your life?

In a minute I’m going to shut up and let you hear Diane Seuss. The thing I love about this book and all her books is that reading her is like being in a conversation with her except she’s doing all the talking, and you are listening to a person who would just as soon be talking to herself. Why are there only sonnets here—128 to be precise? Why do you decide to walk in a blizzard? Why do you see how far you can swim underwater on one breath? A sonnet is like a trapped body: all physical limits and nowhere to run but inside the lyrical imagination. Fourteen lines, again and again. Remind you of your life?

The title of the collection is for a touchstone of Seuss’s, Frank O’Hara, the great New York School poet who worked as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, who invented (again) a confessional, conversational style of writing poetry that sounded right there in the minute, and who in 1966 was freakishly hit by a jeep on a Fire Island beach and died at forty. The title is for a close friend of Seuss’s who died of AIDS. The title is for the voice of these poems, where nothing that happens to the body is out of bounds or shocking.

Familiar themes recur: a childhood in rural Michigan and wonders of the natural world, a beloved father who was sick and died when Seuss was a kid, a resourceful mother, a period of chaos and glamour in New York’s Downtown scene, a son who developed a heroin habit, sex arriving like weather conditions, solitude sought as a companion, and always the need to pee on the side of a road because she is on the run and because she, like everyone else on the planet, dreams of walking around in public and losing her pants. Nowhere in this book does Seuss reference her accomplishments as a writer and teacher and the numerous awards she’s won. The established literary world doesn’t stir what she writes.

More than anything, it strikes me, she loves the individual sentence and line. She loves them so much each is required to build a world that is there and at the same time includes its opposite: her dead father in the coffin of Emily Dickinson; artists she met who were famous and left her with a lasting sense she was invisible; a blizzard producing a ceasefire between sisters. You don’t feel the poems arrive whole like memories or anecdotes. You feel line one pulls behind it line two like an ant carting along a bread crumb. In each poem, the fourteen little stories build a collage that buzzes with tension. Also joy. This is a writer whose pleasure in building language knocks you over and makes you feel some responsive pleasure, even if she is talking about grunge and illness and moldy things found under splintery floorboards. The comma is her preferred punctuation mark. The comma used as a form of and and in place of other conjunctions that might argue a case or an understanding. There is no resolution and little consolation in these poems apart from residue left by desire. Even plucked from different poems and arranged as a list as I am about to do now, Seuss’s lines produce a monologue uniquely hers: intimate, rapturous, deathy, and wry.

Here she is on the road:

Once, I took a Greyhound north across an icy bridge . . . / a bridge lined with stars unscrewed / from the sky and fastened to the cables and the towers with black / electrical tape, bus windows fogged-over from all the human breathing, / lovers, masturbators, numb frostbit moon going black around the edges.

And in another maybe less safe vehicle:

I had no squeamishness, I’d eat alligator, rabbit / with the head on, fish eggs, eyes, hitchhike playing / the mouth harp, got into a helluva jam, sitting in the cab / of a truck between two nasty bumpkins, saved when / a turkey vulture crashed through the windshield into / my lap.

And on that time she met those famous men:

Yes, I saw them all, saw them, met some, Richard Hell, / Lou Reed, Basquiat, Warhol, Burroughs, Kenneth Koch, / . . . I hope you are not titillated by it, their loathing / of women was indisputable, sometimes leaving genuine bruises, / more often just a sneer or no eye contact, the eyes wandering / off like dogs looking for something worth peeing on.

And on the way her mind works in opposites:

Here on this edge I have had many diminutive visions. That all at its essence is dove-gray. / Wipe the lipstick off the mouth of anything and there you will find dove-gray.

or

They cut me stem to stern and out came a little / drug addict.

or

My favorite scent is my own funk, my least favorite scent, other / people’s funk, and this, my friends, is why we cannot have nice / things.

And on poetry:

Even poetry, though built from words, / is not a language, the words are the lacy gown, / the something else is the bride who can’t be factored / down even to her flesh and bones.

or

Poems are someone else’s clothes I slipped / into so I could skip town.

And on attraction:

All desire should be illicit, its / fulfillment transpiring in wet, blue-shadowed places where a life like a shirt comes / undone.

or

But you know how coyotes are, / that high laugh-cry that throws salt into your wound at the time / of night you’re already bedded down in your loneliness.

or

The world today is wet, the world is wet, trees / not so much dripping as exuding, walnuts dropping, / bouncing off the roof, sound of a 100 small skulls / thwacked with a bat, . . . / love stops, let’s not say / otherwise, out of the blue it arrives chuffing black / smoke then departs with a scream like Spanish trains / in the ’70s, jump on, eat a bocadillo, blow a wet harmonica / with a guitarist you’ll never see again who plays Dylan’s / version of “Baby Please Don’t Go.”

And on dreams that are your life:

I dreamed of it again, my dad’s body lost to us again but finally / found again, we set him in Dickinson’s coffin, . . . / I could see the stitches holding my dad’s eyelids shut, but lo / and behold his eyelashes, so long they tangled now and then, were / still intact, and at his throat, like Emily’s, a nosegay of violets, / . . . I don’t / know why I miss Emily so, and him, why die, why dream?

The life that emerges from these fragments and shards, though often reflecting on disappointment and sorrow, is outwitted in each poem by the exuberance of creation that comes flying at us from the poet. It’s part of the paradox of writing and reading that we lose ourselves both in the making and consuming of literature. frank: sonnets is a great book to steal from. “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do without,” writes Seuss. All the fun of writing is in finding out what doesn’t need to be there. Learn as much as you can from what she’s doing. Break it down. You won’t be able to imitate it, but try. Even if you’re not a writer, your brain will shake itself out and walk around. Reading Seuss, you are her. You could be her. You could never be her.

Laurie Stone is a regular contributor to the Women’s Review of Books. She is author most recently of Everything is Personal, Notes on Now, which features several essays that originally appeared in the WRB.