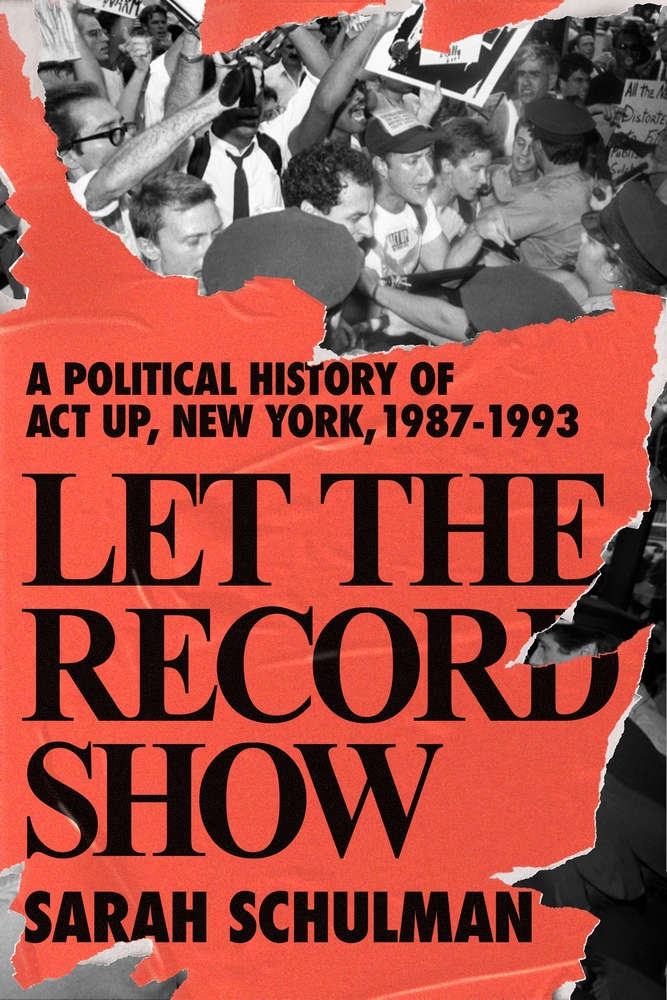

Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 By Sarah Schulman

Reviewed by Nino Testa

While she makes a clear and convincing argument against the deification of particular individuals, it is difficult not to hold Schulman herself up as an unsung hero of the movement.

In the early days of the 2020 quarantine, as we were all still fumbling to wear our masks properly and visualize an invisible six-foot radius, the Twitter handle for ACT UP NY shared a provocative pair of photographs, drawing an explicit comparison between the politics of HIV and of COVID-19. On the left, the unforgettable photo of David Wojnarowicz’s black leather jacket, reading “If I die of AIDS—forget burial—just drop my body on the steps of the FDA.” On the right, a black face mask reading “If I die of COVID-19—forget burial/drop my body on the steps of Mar-a-Lago.” Many online found the tweet distasteful or disrespectful to AIDS history, but Matthew Rodriguez, a journalist and writer for The Body (a preeminent HIV/AIDS resource), urged us to resist “the instinct to keep [AIDS history] like a cabinet curio, behind plate glass, and to leave it undisturbed,” while AIDS and a racist healthcare system are still with us. As we mark the fortieth anniversary of the first reported cases of HIV, with the epidemic ongoing, critical AIDS histories still have much to teach us about the politics of the current moment.

In the early days of the 2020 quarantine, as we were all still fumbling to wear our masks properly and visualize an invisible six-foot radius, the Twitter handle for ACT UP NY shared a provocative pair of photographs, drawing an explicit comparison between the politics of HIV and of COVID-19. On the left, the unforgettable photo of David Wojnarowicz’s black leather jacket, reading “If I die of AIDS—forget burial—just drop my body on the steps of the FDA.” On the right, a black face mask reading “If I die of COVID-19—forget burial/drop my body on the steps of Mar-a-Lago.” Many online found the tweet distasteful or disrespectful to AIDS history, but Matthew Rodriguez, a journalist and writer for The Body (a preeminent HIV/AIDS resource), urged us to resist “the instinct to keep [AIDS history] like a cabinet curio, behind plate glass, and to leave it undisturbed,” while AIDS and a racist healthcare system are still with us. As we mark the fortieth anniversary of the first reported cases of HIV, with the epidemic ongoing, critical AIDS histories still have much to teach us about the politics of the current moment.

Enter Sarah Schulman’s remarkable new work of public history, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993. Founded in March 1987, after years of governmental and cultural indifference to the AIDS-related deaths of Black and brown people, gay men, intravenous drug users, trans women, Haitians, and other marginalized groups, ACT UP became the central organizing force of AIDS activism in the United States, one of the most culturally and politically impactful social movements of the twentieth century. Schulman sets the scene of the “apocalyptic story” of AIDS in appropriately stark terms: “This is the story of a despised group of people, with no rights, facing a terminal disease for which there were no treatments.” Schulman, herself an early member of ACT UP, is clear about her motivation in writing this book: to preserve and disseminate the lessons learned and tactics used to effect social change. “Historicizing ACT UP as an organizational nexus of a larger culture of resistance by people with AIDS (PWAs) invites all of us, in the present, to imagine ourselves as potentially effective activists and supporters no matter who we are.” In the pages that follow, Schulman does more than establish an extensive history of the movement, she guides us through the transferable principles that made it successful and encourages us to let this history do real work as we strategize interventions in response to the countless crises of our world. Throughout the book, she repeats the underlying philosophies that organized ACT UP’s work: a separation of direct action and social services, building the broadest possible coalition, trusting the simultaneity of actions, and not attempting to develop consensus within a dynamic group. Schulman also offers extended meditations—both her own and perspectives from interview subjects—about the failures of the organization and the human relationships that caused those failures, always with an eye on praxis: “Understanding mistakes does not undo successes. Learning to hold both, at the same time, is necessary in order for new generations of people under attack to feel capable of moving forward.”

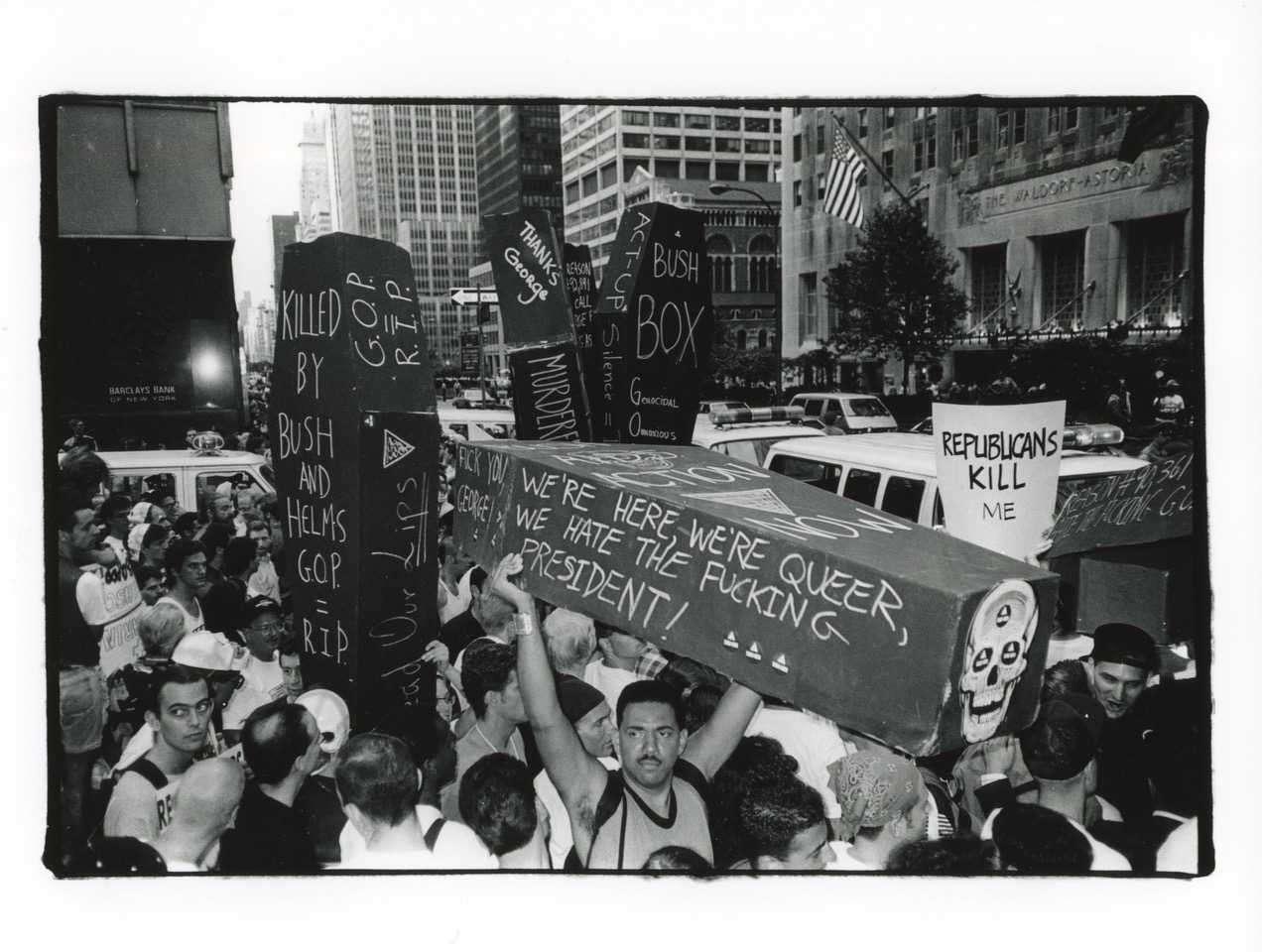

ACT UP protesters put civil disobedience and direct-action tactics to work outside the Waldorf Astoria, 1990. Photo credits: Dona Ann McAdams.

ACT UP protesters put civil disobedience and direct-action tactics to work outside the Waldorf Astoria, 1990. Photo credits: Dona Ann McAdams.

Schulman describes the book as a kind of people’s history, the collection of personal narratives, experiences, and reflections of those most immediately involved in ACT UP: “I am not a trained historian, and this is not a cumulative, documented history beyond the testimonies of the people who created it.” Since 2001, Schulman, in collaboration with filmmaker and AIDS activist Jim Hubbard, has conducted nearly 200 oral history interviews as part of the ACT UP Oral History Project. Anyone who has perused these interviews at actuporalhistory.org, or used it in the classroom, knows that it is an indispensable tool for teaching and learning the history of AIDS, but it is also an unwieldy archive, difficult to dig into without a guide or frames of reference. Already, Schulman and Hubbard have utilized this impressive collection as the source material for their 2012 documentary United in Anger, an important narrative primer on ACT UP history. In Let the Record Show, Schulman combs through interview transcripts, organizing them not into some master chronology but into thematic groupings, case studies, and narrative retellings. Schulman makes clear that this book is meant to be read and used as a guide for making social change: I think about the ways that one might utilize this hefty text by assigning these case studies in a classroom as companions to primary historical materials and a guide to the ACT UP Oral History Project, but I likewise imagine individual chapters circulating in consciousness-raising groups, community centers, and activist organizations.

In a series of case studies, Schulman narrates ACT UP’s most important and controversial actions—like Stop the Church (1989), Storm the NIH (1990), and the Ashes Action (1992)—which, she argues, have otherwise been rendered caricatures in the popular imagination, their political and cultural significance reduced to mythology. Let the Record Show restores the historical urgency and specificity of these actions and their imagery. For instance, Schulman offers extensive analysis of the aesthetics and political tactics of Gran Fury, the activist visual art collective that designed ACT UP’s most iconic agitprop and radically redefined the popular imagery used to represent people with AIDS. She makes the case that these now indelible images of protest art contributed, in real time, to the development of a particular activist consciousness that transcended weekly meetings and direct actions: “It can be said that the art of ACT UP created a new kind of person, one who was living with HIV (infected or not) and who could change the world.”

One of the critiques of dominant AIDS histories is that they focus primarily on the experiences and activism of a handful of white gay men. In many ways, ACT UP has been wrongfully remembered as a white man’s organization. Schulman re-narrates this whitewashed history of the organization as one whose civil disobedience and direct-action tactics were learned from Black civil rights activism, and whose patient-centered healthcare framework (“People with AIDS are the experts”) was the product of decades of feminist organizing done by early ACT UP members like Marion Banzhaf, many of whom were lesbians. She doesn’t just pay lip service to the diversity of ACT UP, she offers detailed historical analysis of the formation of ACT UP Puerto Rico; a four-year campaign to change the CDC’s definition of AIDS (which would “allow women and poor people access to benefits and experimental drugs and studies”); and solidarity work with HIV-positive Haitians who were being incarcerated in Guantanamo.

While Schulman centers the racial and gender justice work done by ACT UP, she also documents the routine experience of racism that people of color experienced in the organization. Her analysis of the infamous 1992 “split” of ACT UP and the Treatment & Data Committee (which became the independent Treatment Action Group), details the racial and gendered power dynamics that, some argue, contributed to the organization’s declining impact. In this way, Let the Record Show offers a substantive racial and gender analysis, as opposed to a cursory review of a few high-profile women or people of color in the organization, as we might find in other public histories of the movement.

Schulman is in conversation with decades of critical work that refocuses our understandings of intersectionality in the experience of people with AIDS, and she explains how the most privileged group impacted by AIDS, gay white men, came to stand in as the most visible representative of the movement. But she is making an even more fundamental critique about how we narrate the history of AIDS activism through an individualistic, neoliberal framework. She decimates the myth of Larry Kramer as the “founder” of ACT UP, but more importantly, she tells a de-centralized history where ACT UP isn’t the accomplishment of a few heroic individuals (a la the mega-successful 2012 David France documentary How to Survive a Plague), but the achievement of a diverse, collective movement. Schulman is asking us to consider a paradigm shift, not just in how we narrate the history of AIDS but in how we narrate the history of social change. We are reminded throughout Let the Record Show that ACT UP was actually not a single organization with clearly identifiable leadership, but was instead made up of countless smaller affinity groups that pursued their own political actions as well as supporting the larger initiatives of the organization, all “united in anger, and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.”

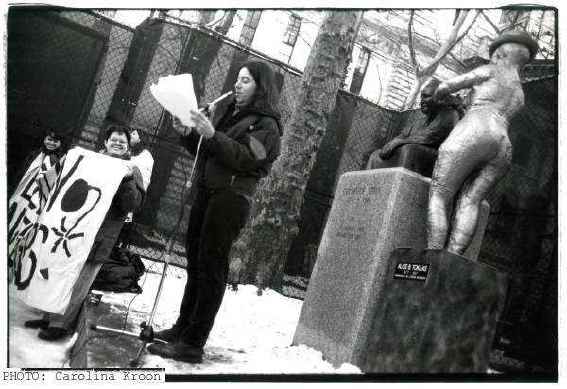

Sarah Schulman, a founder of Lesbian Avengers, at a 1993 lesbian visibility action installing a statue of Alice Toklas in Manhattan.Schulman weaves together the oral history interviews of ACT UP members and her own recollections and analysis, always mindful of the narratives she is constructing and closing down through her own writing; she makes space for the messy moments of historical experience and interpretation and highlights discrepancies between her own recollections and those of her subjects. While she makes a clear and convincing argument against the deification of particular individuals, it is difficult not to hold Schulman herself up as an unsung hero of the movement. Perhaps best known for her powerful AIDS novels People in Trouble (1990) and Rat Bohemia (1995), Schulman is a prolific writer whose nonfiction includes My American History: Lesbian and Gay Life During the Reagan/Bush Years (1994), a collection of her journalistic AIDS writing, and Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America (1998), a meditation on how mass media so egregiously misrepresents the realities of AIDS and gay life. I can think of no other person who has done more to document, interpret, and disseminate histories of ACT UP, and the AIDS epidemic more broadly, than Schulman herself.

Sarah Schulman, a founder of Lesbian Avengers, at a 1993 lesbian visibility action installing a statue of Alice Toklas in Manhattan.Schulman weaves together the oral history interviews of ACT UP members and her own recollections and analysis, always mindful of the narratives she is constructing and closing down through her own writing; she makes space for the messy moments of historical experience and interpretation and highlights discrepancies between her own recollections and those of her subjects. While she makes a clear and convincing argument against the deification of particular individuals, it is difficult not to hold Schulman herself up as an unsung hero of the movement. Perhaps best known for her powerful AIDS novels People in Trouble (1990) and Rat Bohemia (1995), Schulman is a prolific writer whose nonfiction includes My American History: Lesbian and Gay Life During the Reagan/Bush Years (1994), a collection of her journalistic AIDS writing, and Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America (1998), a meditation on how mass media so egregiously misrepresents the realities of AIDS and gay life. I can think of no other person who has done more to document, interpret, and disseminate histories of ACT UP, and the AIDS epidemic more broadly, than Schulman herself.

In the closing pages of Let the Record Show, Schulman reflects on her own traumatic experiences of loss throughout the AIDS epidemic, a poignant reminder (like the remembrances sprinkled throughout the book), of the visceral motivation of survival in a mass death experience that motivated so much of the activism she now documents as history. One is left with an overwhelming sense of gratitude—not only for the incredible amount of labor that it took to remember, collect, preserve, narrate, and interpret the events of this book, but for the world-changing activism from which we have all benefited in such incalculable ways.

Nino Testa is the Associate Director of the Department of Women & Gender Studies at Texas Christian University, in Fort Worth, Texas. He lives in Dallas where he also volunteers for The Dallas Way: An LGBTQ History Project.