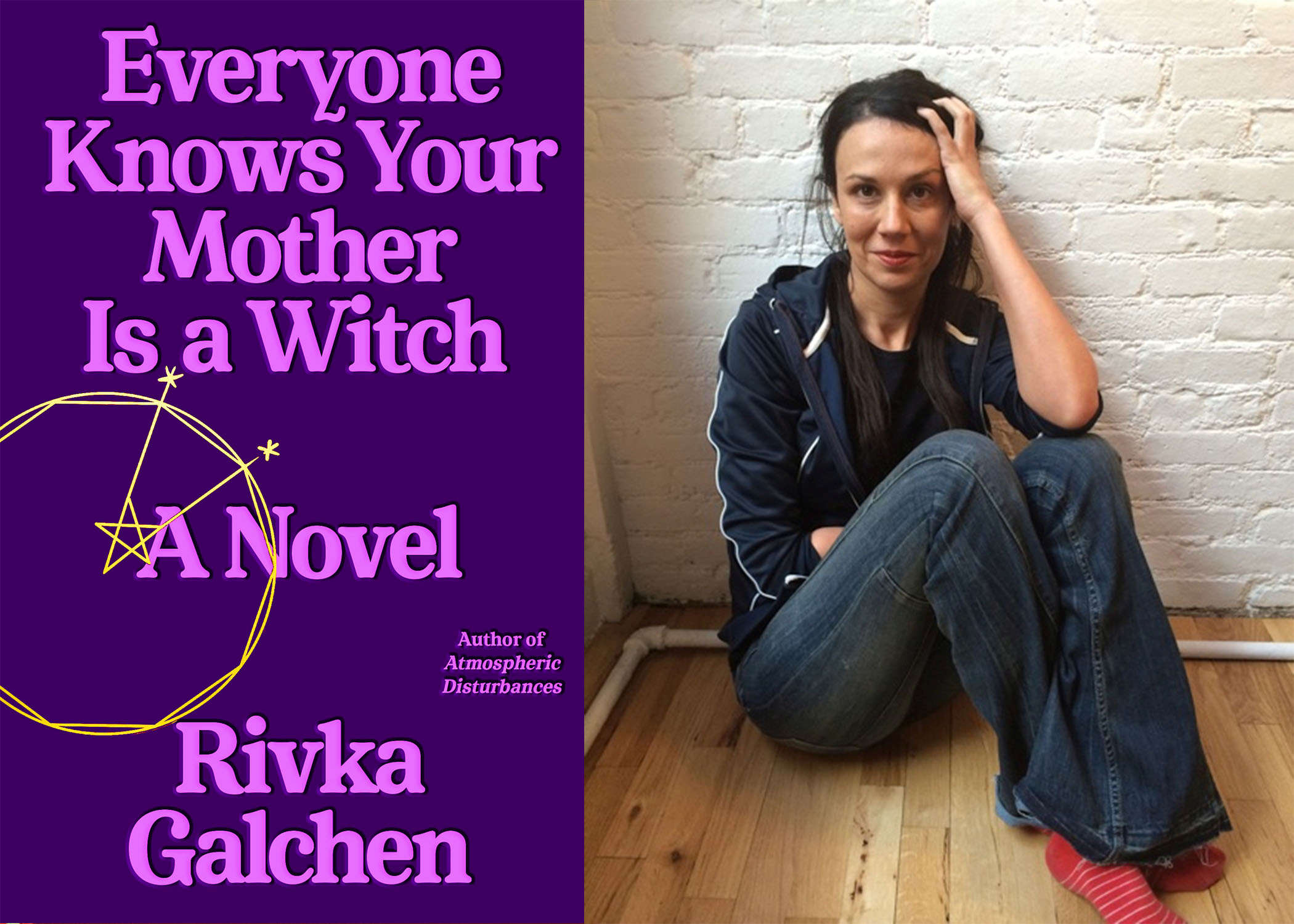

Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch By Rivka Galchen

Reviewed by Charis Caputo

And as the town rallies against Katharina, her ‘resplendent underside’ is eclipsed by her ‘off-putting way.’

Rivka Galchen’s oeuvre is famously hard to summarize. I first encountered her as a prolific New Yorker contributor who casts the slant, revealing light of her strange mind on subjects as disparate as fracking, hospital food, and children’s literature. I fell in love with American Innovations (2014), her collection of contemporary reworkings of classic short stories like Joyce’s “Araby” and Borges’s “The Aleph.” Her essay collection, Little Labors (2016), has similar range. Galchen’s work—journalistic or creative—shows an ambidextrous ease with both scientific and literary knowledge (she holds an MD as well as an MFA), and perhaps it is from the cross-fading of these categories of knowledge that her surreal, precise fiction derives its power.

Rivka Galchen’s oeuvre is famously hard to summarize. I first encountered her as a prolific New Yorker contributor who casts the slant, revealing light of her strange mind on subjects as disparate as fracking, hospital food, and children’s literature. I fell in love with American Innovations (2014), her collection of contemporary reworkings of classic short stories like Joyce’s “Araby” and Borges’s “The Aleph.” Her essay collection, Little Labors (2016), has similar range. Galchen’s work—journalistic or creative—shows an ambidextrous ease with both scientific and literary knowledge (she holds an MD as well as an MFA), and perhaps it is from the cross-fading of these categories of knowledge that her surreal, precise fiction derives its power.

Galchen’s second novel Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch, is (unsurprisingly) something no one expected from her: historical fiction set in the seventeenth-century German duchy of Württemberg. The protagonist is Katharina Kepler, mother of the famous astronomer Johannes Kepler. In the “ominous” spring of 1618, Katharina is charged (in the novel, as in the historical record) with practicing witchcraft against her neighbors. So begins a protracted trial during which the town of Leonberg, racked by plague, the onset of the Thirty Years’ War, and the enclosure of public lands, turns against the mother of a distinguished and contentious scientist. The townspeople pile on, blaming their illnesses, family deaths, and bad harvests on her. They allege poisonings, “passing through locked doors,” and riding a goat (or a calf) backwards to death and roasting it.

Facing financial ruin and possible execution, Katharina first fights the charges in Leonberg, then flees to her son Johannes’s home in Austria. Upon her arrival, she falls temporarily ill. In one of several metafictional scenes, Johannes’s wife reads to the sick Katharina “from a story that was familiar in essence, but whose details were strange.” This might describe the feeling of Galchen’s novel itself, the familiar tale of a woman scapegoated as a witch, situated and told in a way that is funny, sad, and suffused with the weird, incandescent logic of a story-within-a-story distorted through a fever dream. Composed mainly of fictional testimony, trial records, and letters that are based partially on real documents and informed by a wide range of secondary sources, the novel gives us a sort of parallax view, raising questions about perception and reality.

Perhaps it’s worth noting that it was Johannes Kepler who discovered the parallax effect. A key figure in the transition from ancient to modern cosmology, Kepler is most famous for his laws of planetary motion, which embraced Copernican heliocentrism while laying the groundwork for Newtonian mechanics. He was also a devout Protestant and considered himself a metaphysician as well as a scientist, working at a time in which there was no clear distinction between astronomy and astrology. In the novel, Kepler has just left his post as the emperor’s astrologer in politically unstable Prague (officially Catholic) and been excommunicated from Württemberg (officially Lutheran) because of his supposed Calvinist heresies. The accusations of witchcraft against Kepler’s mother are often attributed to Kepler’s precarious position in this shifting Counter-Reformation landscape, as well as to a sort of proto-sci-fi manuscript he wrote and circulated around this time in which his protagonist’s mother consults a demon about space travel.

While both of these factors are addressed in Everybody Knows, Johannes remains a relatively minor character. And if you find his politico-religious situation confusing, you’re not alone. His mother, an illiterate woman in a world in violent flux between residual paganism, Catholicism, and various strains of Protestantism, leaves the finer points of theology to others: “I was born the year Luther died. I took Catholic communion only one time, in error. My daughter Greta is married to a pastor who says that’s okay.” She is also told it is “okay,” theologically speaking, to wear face powder and to sing certain songs to sick babies, though it is not okay to use incantations or believe that animals have souls. Righteousness is a slippery thing, defined by the mutable expectations of others, and Katharina ambivalently tries to conform to those expectations, though her cosmology is (dangerously) steeped in a kind of syncretic animism.

In many ways, Galchen’s rendering of Katharina fits our popular conception of witches, or of the type of woman likely to be accused of witchcraft: she is an elderly, propertied widow, a matriarch and healer so attentive to plants, animals, and humans alike that she seems always to collapse the boundaries between them. Her cow, Chamomile, receives as much care and affection as her grandchildren. She notes that her son Christoph is “not friends with dill.” She prescribes her neighbor Simon cowslip blossoms for his cough (which she overhears from a distance) because, in her arcane apothecary logic, “a lung is a sheep.”

Katharina is also a busybody and a gossip. Simon—who acts as her male guardian in the proceedings and to whom she gives the informal testimony which makes up part of the novel—was at one time repelled by Katharina’s interference (trying to cure his cough, for example). Simon is a very private person who, like many characters, is guarding secrets of his own, never brought into clear focus. But Katharina, we learn, eventually won Simon’s friendship by leading a party to rescue him and his home from a flood, “calling out plans,” as he recalls, “in what I now recognize as her usual off-putting way. Her intrusive nature had this resplendent underside.” Katharina, though generous, can indeed be abrasive. She is defiant of enemies and authorities. She refers to the ducal governor—a venal usurper—as “The False Unicorn.” Of Ursula Reinbold, the glazier’s wife who initiates the witchcraft trial by accusing Katharina of using dark magic to inflict a mysterious illness (syphilis maybe?), Katharina says privately: she “has no children, looks like a comely werewolf … and everyone … knows that as a young woman Ursula took powerful herbs given to her by the apothecary … with whom she had an affair.”

“Everybody knows” is a refrain of this novel—the language here is rich, but also contemporary, demotic, wry—in which gossip and slander not only propel the narrative but seem to constitute and negate an unstable reality. When another woman accuses Katharina of assaulting her daughter, Katharina retorts, “Everyone knows Wallpurga Haller tells fortunes by measuring heads—a superstitious and unlawful practice, which, besides, she is no good at.” We are in a world where you’re only as safe as your reputation. Indeed, Simon’s oft-repeated motto is “see no monsters,” for monsters are only created through perception. And as the town rallies against Katharina, her “resplendent underside” is eclipsed by her “off-putting way.” Even her son Johannes, after an exchange that annoys him (Katharina has implied that eating with a fork is an affectation he acquired in Prague), bursts out: “I was thinking to myself … [how has] Mama, who works so hard, who is kind even to animals … been so viciously turned on? … But living again with you here, I remember.” Unfazed, Katharina interprets: “He was saying I am a person of substance, which I have always felt. And maybe this is because I had to be a mother and a father both to my children.” Subtly, the sexism here is revealed: Katharina is an old woman made strong by a difficult life—hostile in-laws, an unreliable husband who disappeared (dead or absconded, no one knows) in the religious wars, the loss of many children and grandchildren—she is no good at playing games.

But she is also no misanthrope, nor does she ever become a monster. Actually, the word empath comes to mind. She appears so finely attuned to her surroundings that visions often intrude on her testimony, decontextualized, animistic glimpses of pain: “An image came to my mind, of sickly grapevines being cut, and bleeding.” She resolves to see the best in her accusers; when her daughter loses a pregnancy, she resists blaming her enemies: “sad things are so commonplace. As you say Simon: see no monsters.” You don’t expect a book about witches to be so full of tenderness, subtlety, melancholy, as this one is. We watch Katharina care for children we know will soon die. When she is thrown in prison, she tells her daughter, “I liked at least half of the women I met in the thieves’ tower.” As the book concludes, the thread of the trial is nearly lost to plague, warfare, time. Katharina suffers, everyone suffers—“to love others,” she says, “is to suffer”—and she bears it with as much dignity as she can.

In the final chapter, Simon, who we now see is the story’s meta-author, tries to sell his manuscript at auction. First he pitches it as the story of “a good woman, a hardworking widow, exemplary, facing the worst calumny, with dignity,” but no one has any interest. Next pitch: “a tale of the viciousness that lurks in village life!,” but he grows “tired of pretending.” Later, an Englishman who has just sold an erotic story about a gold-digging adulteress gives Simon some advice: “People don’t like an old lady story, you know? I wouldn’t lead with that part.”

This is obvious meta-commentary in a book that does not conform to easy marketing categories. You’d expect a novel with such a sassy title—not to mention a pink and purple cover—to fall back on the “witch” tropes of contemporary pop-feminism: either semi-ironic postmodern paganism or the strident reappropriation of witchcraft as validation of female anger. But something subtler is happening here. We’re within the ambiguous cosmology of early modern Europe, where science is inextricable from magic, where you can be executed for witchcraft, and yet the Lutheran minister insists that “witches aren’t even real,” they’re just delusional old women to be “pitied, not punished.” Which kind of misogyny is worse?

In a particularly surreal chapter, Katharina travels to a bathhouse near Ulm full of naked women resembling “so many badgers and otters.” Here, she is told, resides a “doctor” who can tell a woman whether or not she is a witch. The doctor’s divination is inscrutable, and when she offers to get him a horoscope in return, he answers that astrology is “all garbage,” and she trusts him because “he saw delphinium as I saw delphinium. As a plant capable of good and evil both.” Galchen, as she so often does, uses spiraling confusions and negations to open up an uncanny space, a “region of unlikeness” (to borrow a phrase from one of her short stories) in which nothing is quite itself, and mutually exclusive realities become compatible. Somehow witches both do and do not exist and Katharina both is and is not one, and this both matters and does not matter.

This is a beautiful, slippery book that gives much if you can grasp it. As soon as I finished, I wanted to read it again, not only because the characters were good company but because, like life itself, it produced in me that paradoxical pleasure of having not quite understood.

Charis Caputo is an MFA candidate in NYU’s Creative Writing Program and Assistant Editor of Women’s Review of Books. She holds an MA in History from Loyola University Chicago.