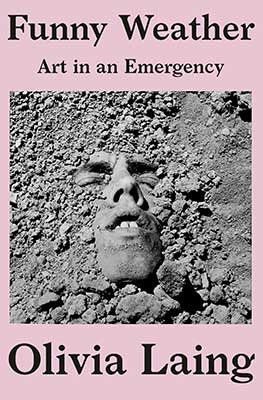

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency

By Olivia Laing

Reviewed by Laurie Stone

For her debut novel Crudo (2018), Olivia Laing devised the narrator Kathy, who guides the reader through eight or so months of Laing’s life in 2017, when, fearing marriage, she married a man old enough to be her father and, when, stirring thoughts of apocalypse, Trump was threatening to bomb North Korea and Nazis gained a warmer reception in the US than they’d had in decades. Kathy is Laing as Kathy Acker, punk appropriator of any text not sealed in a bank vault. Kathy is every female who has attended the movie “Womanfuture” and walked out.

I loved Crudo and Laing’s jump cuts from memoir to news coverage to art criticism to namedropping gossip. I loved the effort she made to create the simultaneous big and little of things in a time of panic and disbelief. Her next book, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency—a collection of essays and art criticism—has perhaps been rushed out on the coat tails of Crudo’s acclaim and arrives when life is worse. How do you even publish a book these days, Laing wonders. How do you publish a book as if things are okay? Same as it ever was. You don’t. You can’t.

Many of the pieces collected were commissioned as introductions to books or written as columns in the Guardian, frieze, and New Statesman, among others, and are addressed to readers assumed not to know much about figures as significant as Agnes Martin, David Hockney, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Hilary Mantel. The writing sometimes feels dutiful, and Laing seems a bit bored by her role as usher. We’re not sure what these figures mean to her. More often, fortunately, the writing captures the breathless sweep of Laing’s novelist voice, observing the way we keep living while the air burns and senile white men plot to bury us. Again and again, she asks what art can do at a time like this. The answer: No one knows, except to remember rapture and remind us of love. Silence still equals death, but so might speech in an age of lies.

Reading through these tributes to writers and visual artists, a through line of intimate involvement emerges. It’s about the AIDS crisis that burst into our lives in the 1980s when Laing, who is 43, was too young to have experienced it first hand. The through line concerns the directaction politics of Act Up that profoundly changed global consciousness about people with AIDS. Laing looks back with awe and longing to a time when activists had the agency to affect public policy. Four pieces leap out of this book especially, stabbing the reader with ideas and passion. One is about the artist David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS in 1992. Here Laing quotes a passage from his 1991 collection of essays, Close to the Knives, that makes the plague at once individual and epic: “the people waking up with the diseases of small birds or mammals; the people whose faces are entirely black with cancer eating health salads in the lonely seats of restaurants . . . piece by piece, the landscape is eroding and in its place I am building a monument made of feelings of love and hate, sadness and feelings of murder.” Later she quotes Wojnarowicz explaining his desire, as a visual artist, to “produce objects that could speak” when he no longer will be able to, and to make objects that make visible what legislation and other strictures sweep out of sight.

Laing deftly honors Sarah Schulman’s brilliant analysis of official forgetting in her review of Gentrification of the Mind, in which Schulman argues that, like the gentrification of the Lower East Side, where so many people with AIDS, who were also poor, were replaced by Wall Street entrepreneurs, so mourning the dead of 9/11 has effaced public grief over AIDS. Writes Laing, “It’s understandable that she might feel bitter at the institutional opulence of the 9/11 memorial to ‘the acceptable dead’, noting: ‘in this way, 9/11 is the gentrification of AIDS.’” (Note: I’ve preserved the British spellings in the quoted text.)

Laing begins her rapturous tribute to artist/filmmaker/writer/gardener Derek Jarman with a keyhole view of her childhood that snaps into focus the stakes for her to write about gay experience, the natural world, and art that doesn’t destroy things in order to be made. “My mother was gay,” she writes, “and the three of us [including Laing’s sister] lived on an ugly new development in a village near Portsmouth, where all the culs-de-sac were named after the fields they’d destroyed. We were happy enough together, but the world outside felt flimsy, inhospitable, permanently grey. I hated my girls’ school, with its homophobic pupils and prying teachers, perpetually curious about the ‘family situation’. This was the era of Section 28, which banned local authorities from promoting homosexuality and schools from teaching its acceptability ‘as a pretended family relationship’. Designated by the state as a pretended family, we lived under its malign rule, its imprecation of exposure and imminent disaster.”

Jarman, too, died of AIDS, just two years after Wojnarowicz. In summarizing the meaning of his nature writing to her, Laing writes, tenderly and pointedly, “Derek still seems to me the best as well as the most political nature writer, because he refuses to exclude the body from his sphere of interest, documenting the rising tides of sickness and desire with as much care and attention as he does the discovery of sea buckthorn or a wild fig.”

The fourth piece that stirs the reader with special intensity is “Feral.” Unique in the book in being entirely a memoir, it meditates on Laing’s decision in her twenties to drop out of university and become involved in the environmental directaction movement. The summer she is twenty, she moves into “a tiny protest camp in Dorset, established by locals to protect a strip of muchloved woodland from being bulldozed for a relief road.” She and the other protesters sleep in the trees to keep them safe (they succeeded). She writes, her descriptive powers at their giddiest, “Teddy Bear Woods was a beach hanger, falling steeply to a meadow. There was a net slung in the canopy, built as a defence for when the bailiffs came. Lying up there among the leaves, you could see the glittering blue ribbon of the sea a mile south. What did we do all day? We made endless trips to gather wood and water, sawed wood, chopped wood, prepped food, washed up. Without electricity, the most basic tasks took hours.”

What does she want? Community? Solitude? A walkabout free of social obligation? A way to get back to the garden that never was? She doesn’t know, and it’s her ability to stay in the unknowing place throughout the essay that gives it its urgency and tension. Living outside is another form of being homeless. “It was the sort of experience I’d longed for,” she writes, “but still I slept with an axe under my pillow... I was frightened all the time. I felt more exposed than I have ever since, almost unraveled by it, paranoid that I was being watched by the inhabitants of the scattered houses whose lights I could see winking through the fields at night.” The more Laing finds beauty, the more she sees risk of its destruction. The more she sees beauty destroyed—in the bodies of those with illness, in works of art that are silenced or erased, in the natural world that is defiled—the more ably she evokes life’s fragility. In May 1968, Jean-Luc Godard declared, “The problem is not to make political films but to make films politically.” The same might be said about essays—how to write them politically.

Throughout this book, Laing doesn’t ask readers to think about something other than their collective sense of powerlessness that does not produce a concerted front of resistance. She reminds us of it without shaming or virtue signaling. And she reminds us as well there is no such thing as distraction, maintaining that every moment in a person’s head has the weight of every other moment in that head. She values our precious and wasted moments, until there are no more moments, because we have died or the world has died. We think about the world dying all the time, Laing knows, and all the time we look at the sky, and plant iris bulbs, and stage stupid arguments with the people closest to us because peace is impossible and because friction reignites the tedium of existence. The gorgeous tedium of every day we are not detained at a border or made host to a virus flying free as a bird.

Laurie Stone is author most recently of Everything is Personal: Notes on Now (Scuppernong Editions, January 2020) and My Life as an Animal: Stories (Northwestern University Press/Triquarterly Press, 2016). She was a longtime writer for the Village Voice, theater critic for The Nation, and critic-at-large on Fresh Air. Her stories have appeared in n + 1, Waxwing, Tin House, Evergreen Review, Electric Lit, Fence, and Open City, among many others. Her next book will be Postcards from the Thing that is Happening, a collage of hybrid narratives.