Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over By Nell Painter

Berkeley, CA; Counterpoint, 2018, 352 pages with color illustrations, $26.00, hardcover

Reviewed by A.J. Verdelle

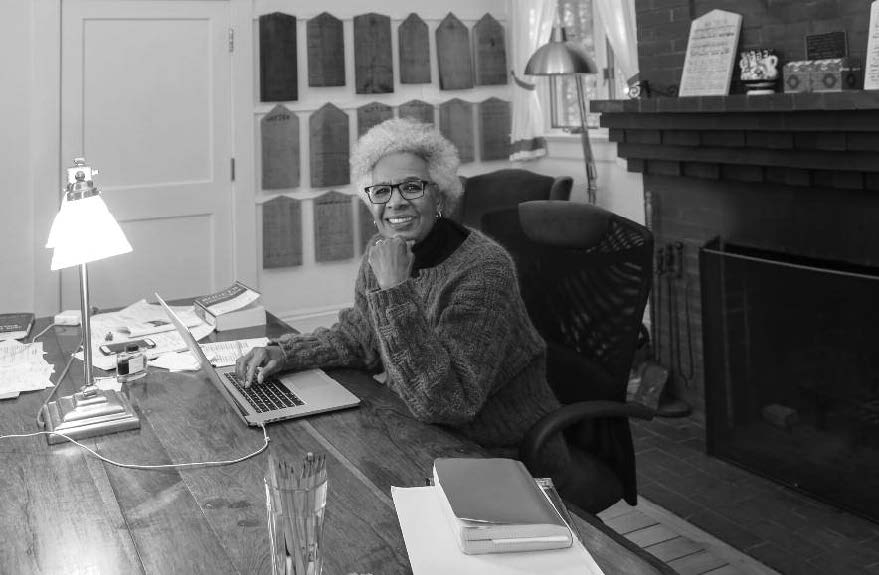

Who can talk about the rock star historian Nell Irvin Painter without explicitly addressing the obvious, which is that her last name is Painter? This is her last name. Painter’s beloved husband has a different last name. When I was briefly a fleck of crystal in Nell Painter ’s orbit, when I taught Creative Writing at Princeton, where Nell Painter was permanently endowed, I could tell Nell was a painter by her palette—skin to hair to coat to shoes to portable accoutrements. Of course, Nell Painter, with her portentous name, would use the freedom of retirement from History as a first career, and choose to launch a second career by going to Art School.

Who can talk about the rock star historian Nell Irvin Painter without explicitly addressing the obvious, which is that her last name is Painter? This is her last name. Painter’s beloved husband has a different last name. When I was briefly a fleck of crystal in Nell Painter ’s orbit, when I taught Creative Writing at Princeton, where Nell Painter was permanently endowed, I could tell Nell was a painter by her palette—skin to hair to coat to shoes to portable accoutrements. Of course, Nell Painter, with her portentous name, would use the freedom of retirement from History as a first career, and choose to launch a second career by going to Art School.

Nell Painter goes to Art School with gusto, and while there, she rediscovers an appreciation for her own hand. Art school awakens her long-held affinity for drawing. Painter possesses sketches she made in her early twenties, in the early 1960s, when her color-sight was awakened in Ghana, where she moved with her parents during the early days of the Black Liberation era. Looking back, Painter recalls how Ghana changed her, before her career in history, but in a patently artistic way:

In Ghana I moved through a humid world of tropical contrasts and color-wheel hues. The dirt was Venetian red, the trees and grass Hooker ’s green. White buildings, red tiled roofs. Cadmium red bougainvillea climbing whitewashed buildings and cascading over fences and walls, some topped with menacing shards of broken brown glass or black wrought-iron spikes testifying to class tensions barricading the wealthy against the grasping poor. Together this colorful landscape and the very black people in white and spectacular clothing altered my vision of everyday life.

Painter ’s keenly trained eye and intellect prompt her to recognize the specific and the theoretical. Painter brings these strengths to her Art Education. Strong and spry and expectant, Painter finishes six years of Art School, completing two brand new degrees, by the striding age of seventy. An alert observer, Painter renders her experience with humor, with skepticism, with anxiety, and in many voices.

Painter is the Edwards Professor of American History, Emerita, at Princeton University. Even though Painter’s prodigious accomplishments in History do not make People magazine, her status in American History has for decades been neon to academic faculty, feminists, historians, and cultural critics. After a huge career, her decision to attend Art School reads in some ways like turning away from a well-traveled road and into the wilderness. Painter is pointedly clear about her attraction to engagement with art: “Art stopped time. Art exiled hunger. Art held off fatigue for what would have been hours as if hours had not really passed.”

Writing deftly about the work of switching gears, and how to rev up to making art, Old in Art School decodes and details the substantive study and artistic processes Painter had to master in her sequence of studios, first at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers, in Newark, and finally, at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Old in Art School succeeds as a story of a budding artist, and also as guidebook: you can design your own art education by following along with Painter ’s readings and reflections on artists in the canon; women artists who Painter appreciates, and elevates, and sometimes befriends; artists who become important to Painter’s interests and to her cultivated eye. From Rembrandt to Faith Ringgold, from Matisse to Alice Neel. Painter also enumerates inspirations and omnipresent impressions. She is in Art School encountering “art works” addressing Barack and Michelle Obama, some of them simply, duly noted, and others worthy of pause and commentary. Most artists also engage with other artists to create a fertile and inspiring context in which to work, and keep time: for Painter, Cassandra Wilson and Abbey Lincoln help create ambience—both women crooners and philosophers who speak to artists and writers and intellectuals of a certain type, like Nell Painter.

At the very beginning of Nell Painter’s Art School career, a fellow student asks her how old she is. Painter, then 64, remarks that there was no hello, no other leading questions, no “Are you a teacher?”, no preliminaries. Just: “how old are you?” Blunt interrogation. It’s no surprise; Art School is known as a cauldron of interrogation—and critique. Painter also approaches her Self and the experience of Art School as a process of interrogation. She describes how she did not quite see herself as old—she was, in fact, starting anew—and yet throughout the narrative, which contains a number of dips and turns, Painter is (mildly) plagued by questions about her age. Painter ’s experience of seeing herself as other people saw her, namely as “old,” relates to DuBois’ assertion that we see ourselves as other people see us, as well as how we see ourselves.

Nell Painter cuts no corners in Art School; she is as thorough as she has been in history. She makes volumes of art work; she tries to fit in. She finishes all her assignments and exercises with gusto and consistency and expectation. She even sits on the floor, and commends herself heartily for being “old,” yet being able to get up and down off the floor at will.

Painter prides herself on diligence and vigor, even as other Art School students, and Teacher Him and Her, and Visiting Artist They and Them are telling Nell that she will never be “A Real Artist.” For one, they suggest she in fact is too old, and they also argue that she probably doesn’t have the talent or the sense of struggle to make the legendary sacrifices that making art demands. Budding Artist Nell listens to this drivel, and resists, and listens again. The degree to which Painter even temporarily succumbs to the wash in negativity her peers and teachers “offer” is probably the least compelling aspect of this otherwise nearly rollicking memoir. Enlivening it is a counter-chorus of many other voices, channeled through Nell Painter’s insight: Nell’s parents, their old friends, Nell’s history friends, Nell’s new artist acquaintances, Nell’s family with their roots in the Bay Area. Hilarious, the voices Nell hears; too funny, the Names she gives them.

Painter prides herself on diligence and vigor, even as other Art School students, and Teacher Him and Her, and Visiting Artist They and Them are telling Nell that she will never be “A Real Artist.” For one, they suggest she in fact is too old, and they also argue that she probably doesn’t have the talent or the sense of struggle to make the legendary sacrifices that making art demands. Budding Artist Nell listens to this drivel, and resists, and listens again. The degree to which Painter even temporarily succumbs to the wash in negativity her peers and teachers “offer” is probably the least compelling aspect of this otherwise nearly rollicking memoir. Enlivening it is a counter-chorus of many other voices, channeled through Nell Painter’s insight: Nell’s parents, their old friends, Nell’s history friends, Nell’s new artist acquaintances, Nell’s family with their roots in the Bay Area. Hilarious, the voices Nell hears; too funny, the Names she gives them.

Painter insists that her age elicited reactions during Art School that ranged from cool dismissal, to critique of her vision with insinuations of the antique. Painter experienced, and accepted, the self-doubt generated by the relatively harsh atmosphere of the Art School “critique.” Painter’s young classmates often looked at curiosity as if it were a relic, an artifact of a time to which they did not belong. In Art School, Painter is confronted by her 20th century-ness, and her stalwart curiosity, as dated conditions. At one point, Painter bluntly states that curiosity represents a great strength. She notes her frequent use of 20th century terms, and wonders whether her ideas were rejected as too 20th century. Painter explores her own attachment to meaning, and learning that’s very 20th century. In the 21st century, presumably, you can be unabashedly attached to just how things look; coherence be damned. Whether the painting or artwork exhibits substance, or skill, or coherence has become passé as a mode of analysis.

Describing one of the artists outside Art School with whom Nell Painter consulted, the narrative is driven by inquiry and curiosity:

Noting my interests in the world, he lent me R.B. Kitaj’s Second Diasporist Manifesto … its untamed monomania blew me back … I settled into its omnidirectional nuttiness … Kitaj knew his book was all mixed up, and he dove deeply into piebald obsession. Kitaj’s weirdness, even though it cost him his reputation as a painter for many years, inspired me.… I had known all along I wasn’t the only one juggling history, group identity, individual proclivities and visual art.

Fully aware that the artist is responsible for motivating herself to make work, Painter ’s intellectual strengths, deep knowledge, visual capacity, and determination all combine to give her wide access to all you have to pull together to make art from this chaotic, fractured world of disciplines and genres, histories and oppressions, travesties and triumphs.

Painter is ultimately able to arrange more situations of artistic discussion where she experiences nurture and gains motivation from critiques that are offered or that she can request, but these nurturing experiences are outside the Art School milieu. Particularly at the graduate level, Painter finds the most engagement and perception with outside artists. Perhaps people closer to her own age. Art School, in other words, is loathe to let go of its breakdown strategy. Speculation about the reasons and/or necessity for Art School cruelty have gone on since the advent of Art School. Perhaps the meanness is supposed to ensure that artists are tenacious enough to hold onto the very vision that Art School portends to critique out of them.

Nell Painter persists. She finishes graduate Art School, but the journey is complicated by a whole series of drama and grief, both quiet and startling. Which brings us to one of the most compelling voices in Old in Art School: Daughter Nell. For most of her six-year experience in undergraduate and then graduate Art Schools, Painter is caring for one or both of her parents.

The dissonance and tension between making art and tending aging parents could not be more stark, and is riveting as a storyline. In happier, more youthful times, Nell Painter and her parents were intellectual activists during a fomenting era in America. Especially among studied, Black, proud intellectuals, Painter and her parents have upright, ‘60s and ‘70s bona fides. They followed DuBois’ theorizing and lived for a time in Ghana, during the Liberation experiments. Nell Painter knew Maya Angelou in Ghana, when Angelou was young and had a last name not yet made famous. The Irvins moved from Ghana to the Bay Area, where La revolution continua, and where Budding Historian Nell went to undergrad at Berkeley. After Berkeley and a Master’s degree from UCLA, she relocated to the Ivied East, and in the ensuing decades there built an esteemed career as an innovative, incisive, and wry academic Historian.

In the book, the most intense period caring for her parents occurs after her mother has already transitioned. In his eighties, Nell’s father asks to be moved from the Bay Area where he had lived, been married, raised Nell, and been widowed—all pieces of a life over the course of seventy years. He wants to move to New Jersey, where Nell can watch over him as he begins his long transition away from this world. For much of the story, even before this last move, her father lay in what Painter describes as a “bitter bed.”

Her father’s depressive saga parallels woefully the (slightly) foreshortened life of Painter’s spunky and beautiful and resilient mother. Nell’s mother, Dona Irvin, predeceased Nell’s father. She published two books in her “old age,” one on the history of Black Methodist churches, called The Unsung Heart of Black America, and the other, I Hope I Look that Good When I Get Old, a guide for aging gracefully that Nell Painter references in the context of her motivations at her own age.

In part because her parents are characters in her memoir, “old” seems too final a choice of word for this determined, intentional adventure in the present tense. Painter is not convincing as an “old” person. Since there is nothing after “old” in our culture—except silent and immutable death—“old” must be defined differently than the can-do years represented by a fit person in her sixties and early seventies even. The many men who keep themselves in power are that age. They do not question their fitness or their age. They do not question themselves at all.

How is “old” defined anyway? Over sixty? Over seventy? Retired? Slowed down? White hair? Can’t do this or that? Can’t sit on the floor, or can’t get up? Full career already done? Many aspects of “old” do not apply to Nell Painter, who has not slowed down. She has had one full career, and has embarked upon another. How old is that?

The memoir is touted as Nell Painter’s eighth book. The list of publications that makes this Painter’s eighth book does not include Soul Murder and Slavery, which has monograph intellectual heft, if not monograph length, and is my favorite example of Painter ’s daring. Most famously, Painter authored the New York Times bestseller The History of White People, which was a visual book. Authoritatively named and unassailably daring, The History of White People started with a question; it is worth reading the memoir just to learn about the stunning process that spawned the book. Creating Black America is another of Painter ’s sweeping, landscapechanging book projects. Old in Art School is subtitled, in a nod to academic form, a Memoir of Starting Over. Rock stars do not start over; they just turn up the amp.

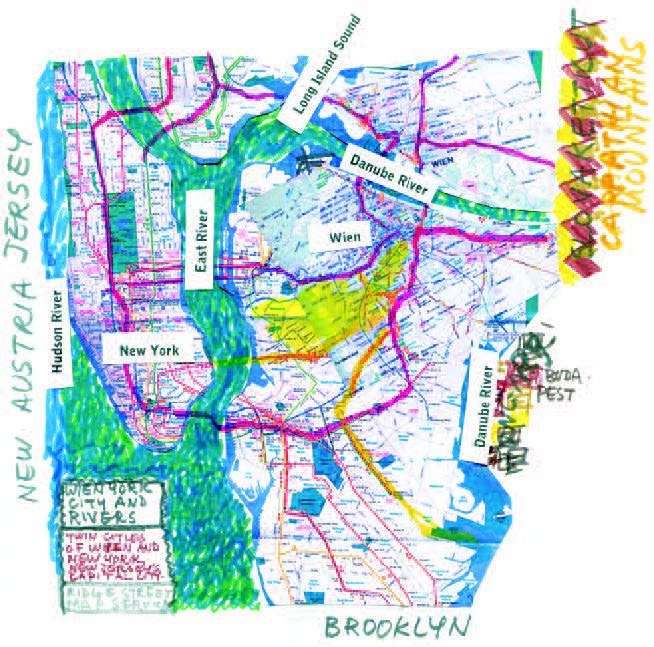

Now, Nell Painter has two bodies of work: her hefty and scholarshipaltering oeuvre of conceptual histories—and, her art. For those perspicacious and hungry enough to follow her artistic progress, there will be the continuing progression of her inventions, including the presumably continuing Odalisque Atlas, or the visual volumes of Art History by Nell Painter, or the completion of her series One Hundred Drawings for Hanneline, or maybe more of her series of maps, torqued away from geography and into the pulsing heart of concept. Nell Painter lives and works and paints in a studio in Newark, NJ. She is a woman of an age, and a woman of strong will. The history will never disappear. And the paintings multiply.

Now, Nell Painter has two bodies of work: her hefty and scholarshipaltering oeuvre of conceptual histories—and, her art. For those perspicacious and hungry enough to follow her artistic progress, there will be the continuing progression of her inventions, including the presumably continuing Odalisque Atlas, or the visual volumes of Art History by Nell Painter, or the completion of her series One Hundred Drawings for Hanneline, or maybe more of her series of maps, torqued away from geography and into the pulsing heart of concept. Nell Painter lives and works and paints in a studio in Newark, NJ. She is a woman of an age, and a woman of strong will. The history will never disappear. And the paintings multiply.

In the end, Painter argues that visual art set her free. This is a bold, sweeping, and unequivocal statement for Painter to make. Although trained as an artist, Painter maintains the specificity and precision of a historian, and she does not speak of freedom lightly. Writing clearly and coherently, about a subject [Art] that cottons to chaos, Painter lets us watch as she tries to pin down aspects of her visionary freethinking. She translates that freedom into concrete invention: Painter now makes collage, and shape shifts, and projects, and paints, and grows exuberant in the infinity of color. It’s expression that is distinct from her visionary contributions to history, that practice of standing rigidly upright rediscovering and reinterpreting established facts. Nell Painter’s trained curiosity carries her through; her art knows no hindrance to crossing chronologies or continents, to shift and reshape time, all on one canvas.

Art takes vivid liberties, whereas history is tied to the archive, and exercises no freedoms therefrom. The connection, then, between art and art history and history did not accrue on the side of art. Freed from the archive, Painter communicates in language which is bodacious and, in moments, color-saturated. Real color, not race color—starts to blossom in the book early. Painter refers to our fantasy of democracy as viridian green, that dark shade of spring. She announces a “Pyrrole orange flash of insight.” The grief colors that come with the loss of a very close friend are “muddy gray mashing down” and “green-tinged brown on an unwashed palette.”

You almost have to go to Art School to let go of the binary of raceassociated black and white, but Old in Art School gracefully offers us that blessing. Colors are infinite and inspiring. If you read Old in Art School, you will learn, from Nell Painter, what it means to speak in color.

A.J. Verdelle is the author of The Good Negress. She teaches creative writing in the English Department of Morgan State University, and teaches fiction and revision in the Lesley University low-residency MFA program in Cambridge, MA.