By Laurie Stone

Election night, when it looked like Biden might lose, I could not think of a reason to get off the couch. Or remain on it. I was awake until 3:30. The next morning I couldn’t see a future beyond the bed, and then a woman texted to say she was picking up chairs we were selling.

Back when I walked on Broadway, I would see a man with flowing white hair I had known in the past. He walked as much as I did and lived nearby. He was often singing to himself and seemed oblivious of me or others whizzing by, and although I did not stop to say hello, I would recall the excitement of first knowing him at nineteen. He had curly dark hair back then and worked for a trade newspaper that reported on scrap metal. He wrote all the pieces in the paper with headlines such as “Steel Prices Stainless” and “Nonferrous Market Resists Rust.” The man I was married to was in law school and as a part-time job did market research at the scrap metal paper. People liked him, and although his research was pretty much fabricated, he was kept on and in time was able to hire me to help him make things up. The full-time writer was older than us and really a musician and songwriter. On weekends he performed in a cabaret, and the man I was married to and I would go see him playing the piano and singing songs of soft satire. It was 1966, and Lily Tomlin was performing there regularly, too, developing the characters she would soon present on Laugh-in. The writer was carefree, and I was grateful to be swept into a world I found glamorous and grown up. He would hold little gatherings in his Hell’s Kitchen walk-up. Actor friends would lean against exposed brick walls, holding juice glasses of wine. He wrote movie reviews for the newspaper, and when he went on vacation, I filled in for him. They were my first published pieces. I would have followed anyone into a theater and the world it led to.

Yesterday we drove to New York City for the first time since the morning of March 6 of last year. Back in my apartment, I saw I'd left a small heater by the couch. It must have been cold. Who were we? We were in the city to have our teeth cleaned, and we went in together and were finished together and walked a little downtown, and although it is a part of the city I have always loved, I did not feel love. Everything was familiar except me.

Some people are waiting for the pandemic to pass over like a weather condition. I am living in an airport lounge.

Recently we watched Reversal of Fortune, about Claus von Bülow, who was accused of attempting to murder his rich wife Sunny by injecting her with enough insulin to place her in a permanent coma. The role requires Jeremy Irons to wear a partly bald hair piece and look ghoulishly pale as he floats around in his imperious and clueless rich-man's way. The film makes you think about the tragic interior design choices of the wealthy and how money buys freedom from accountability. It contrasts Claus's idle drifts from point A to point B to the dervish efforts of his lawyer, Alan Dershowitz, who with his team of students and the aid of maids, hospital workers, bankers, lawyers, and the police, clean up the wreckage left by the moneyed class.

But who would you prefer to have lunch with? Claus or Alan? Witty, self-deprecating Claus any day. The script, based on the book by Dershowitz, advertises Dershowitz as the people's lawyer, fighting for the underdog and the right of anyone to have a strong defense, but you don't think that's who he is. He wants to win a splashy case because as much as Claus wants to fade into the beige drapes, Dershowitz wants the limelight.

I used to practice tap steps waiting for trains. Everyone danced in the subway. The acoustics were good. I used to run to my sister at camp. She’s at the flagpole, twisting her ponytail and smelling of suntan oil. It’s sexy to cut someone’s hair. When I was a bartender, I was generous with the alcohol, wanting people to be happy. For years in the 1960s and 1970s, I read Virago and Penguin editions of books by women: Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, and Colette in a giant gulp, the Margarets Drabble and Atwood, Violette Leduc, Jean Rhys, Gayl Jones, Plath, Sexton.

Before the pandemic, a friend invited me to a party. It was the renewal of a friendship that had come undone for reasons no one could understand. By this time, we had no idea who the other person had become. Still, warmth rose up, and I forgot to eat. The other morning, I recapped the last episode of The Queen’s Gambit for the man I live with. We were in bed, drinking tea. I said that at the end the protagonist chess prodigy teenaged girl is alone in Moscow with a group of old Russian men, who sit outside in the cold, playing chess at café tables. A curtain of tears fell as I spoke. Whatever I told him I cried, and I was sad when there was nothing more to cry about. Who is this girl to me? Every girl who ever wanted something? Remember moving out of yourself on the fast-spinning Tilt-A-Whirl ride? Again. Can we do it again?

Who is this girl to me? Every girl who ever wanted something?

Where I live now—on a farm road upstate—there are tall evergreens and lots of field mice going nuts in the prickly winter grass. I wanted to offer mice to the baby owl who was discovered in the Christmas tree brought to Rockefeller Center. I have always wanted an owl. Who hasn't? Florence Nightingale rescued an owl in Greece she named Athena and took home with her to England. If the small owl came to live here, I wouldn't think it was mine. I would just love it. In pictures of the owl, you can see it thinking: This is like accidentally stowing away on a plane and finding yourself in South America, where you have to learn another language it turns out you have an aptitude for, and it makes you think traveling reveals new parts of yourself as much as it reveals the world. You think about where your wings can take you, and you remember you are adorable to people. Humans think you look smarter than they look. The thing about a human is the hands. Their hands see the future.

Last week our sump pump died during twelve hours of rain. The battery died as well, and the apparatus was screaming its head off as we waited for a plumber. At one point the water in the well rose nearly to the basement floor, and the man I live with and I had to bail it out with buckets. He kept saying we would not be able to contain it, although it was clear if we kept going, we would. I filled the buckets, and he climbed the stone stairs to dump them outside. We got into a rhythm. He was carrying two buckets at a time. Fill, carry, hurl, and soon the level subsided. I knew absolutely we would not fail because no matter what we wouldn’t stop. The man I live with knew absolutely we would not fail, but his way of knowing was to state the opposite.

On the phone the other day a friend recalled the time she gave the man she was involved with a case of crabs. It was forty years ago. They had been in Denmark. He was an artist, preparing a show. She’d grown bored and returned to the States, where she’d slept with this one and that one. “It was a horrible thing to have done, so embarrassing, careless and cruel,” she said, and a few days later when I spoke to her again I could see her judgment had worsened. How could she have done such a thing to someone as kind and loving? I said, “Giving a person crabs because you had sex with other people doesn’t sound that bad to me.” Their affair was winding down, and what she’d done was a way out—cowardly, sure, but to me ordinary. I said, “I have done many worse things.” She said, “Like what?” I said I didn’t feel like recalling the times I had been a heartless betrayer, as examples flipped in my head. I thought that if giving a tender and trusting man a case of crabs was the worst thing you could see looking back, then I could not imagine such a life. By any standard my friend was a more honest and generous person than I’d ever been, and I was amazed she could stomach me.

I am thinking of the kind of hipster that finds compliance with government authority of any kind uncool—a type that, ironically or maybe not so ironically, lines up with Trump defiers of masking and social distancing. And I wonder if it’s thought less uncool to follow orders for the sake of others than to follow orders to save yourself. After the vaccine, will TV shows that resume production pretend Covid never happened? The man I live with says that, if I die, he will return to England. This has given me added incentive to live.

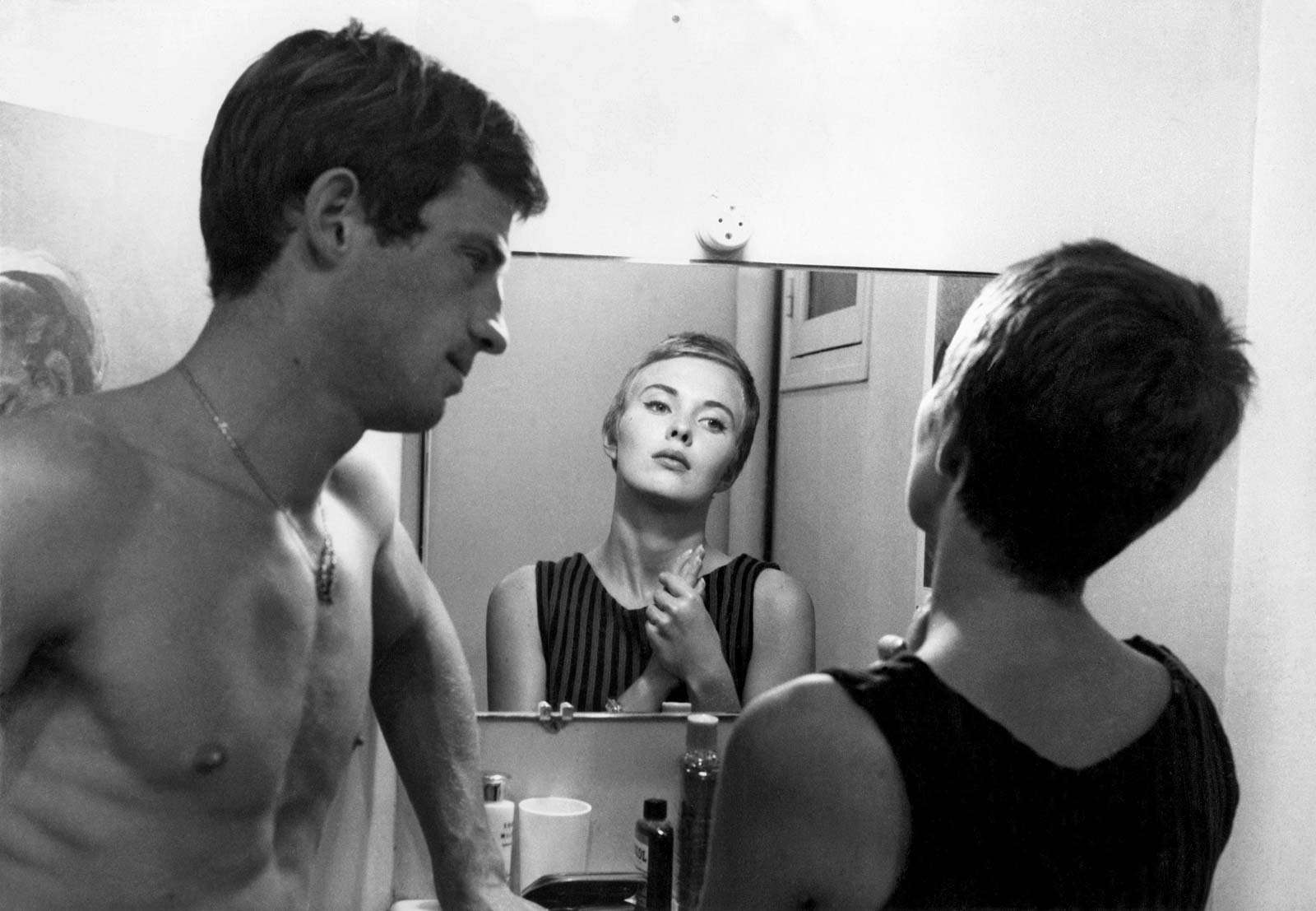

Jean Seberg and Jean Paul Belmondo in Breathless. I have been thinking about rewatching movies and rereading books and the way this makes you feel about your life. I remember seeing the films of Jean-Luc Godard as each came out, year after year, and loving them, especially Pierrot Le Fou (1968) and Weekend the same year. Godard was the kind of person you were supposed to love, and I did. I think it was real love back then.

Jean Seberg and Jean Paul Belmondo in Breathless. I have been thinking about rewatching movies and rereading books and the way this makes you feel about your life. I remember seeing the films of Jean-Luc Godard as each came out, year after year, and loving them, especially Pierrot Le Fou (1968) and Weekend the same year. Godard was the kind of person you were supposed to love, and I did. I think it was real love back then.

It's not as if I have fallen out of love with his films. To fall out of love, you need the wear and tear of daily life or the sudden awareness you have been living in a place where you do not know the language and have been wrong about the words. This once happened when I was visiting Germany. I thought I understood German because the German words sounded like Yiddish and because I started to walk and dream with the music of Germany in my head. I could taste the meaning of the words in the crusty bread.

Last night on Godard’s birthday, we watched Breathless (1961) again. I don’t remember the last time I saw it, but I remember the first time. Not what I thought about the movie. I don’t remember that. I remember who I was. Where could I have seen it? The Bleecker Street Cinema, probably. I remember the jersey tops with horizontal stripes worn by Jean Seberg. I wanted to wear a top like that. I thought Jean-Paul Belmondo was beautiful. I don’t know what I thought, really, but the film with its energy and jumps cuts and a couple of times direct address to the viewer, and the music and sense of Paris and being a girl/woman on her own, this appealed to me when I was a young girl/woman. I think, more than anything, seeing Seberg on the street with her not-even-trying-awful French accent called to me because she lived in a hotel.

Seeing it now, I didn’t remember any of it as it actually is. I didn’t remember that Belmondo pursues Seberg, and she’s not sure about him, which he likes, although he pretends not to. Somehow you think she understands that were she to act like she was falling for him, she would never see him again. I didn’t remember the idiocy of their conversations that hover on the edge of boredom, the way the whole movie does. There is already a kind of boredom about life in these people and in the man who filmed them. Godard’s camera loves each of them more than they feel for each other. They aren’t sexy together. No heat comes off them. They kiss fake. They are two pretty birds on adjoining perches, fluffing out their feathers and pecking a bit on the other’s wings before hopping off in other directions.

I didn’t remember that Seberg turns him into the police or that everyone finds Belmondo’s character, Michel, insufferable, while he doesn’t see it. He’s petulant, pushy, oblivious of Seberg’s wishes or those of anyone else. The way the film thinks about women and understands women has nothing, really nothing whatever to do with how female people understand the world and the ways they’re perceived in it. The job of a woman in the world Godard depicts is to pretend not to see the contempt in which women are held. It’s a full-time job. It’s sometimes all any woman has time to do. I didn’t care about Godard’s infatuation with movies as he made a different kind of movie, although there is something to love about that. I’m just not the person to love it is all.

I wasn’t bored as I lingered on the verge of boredom, like the characters. I could see Godard had made a piece of jazz from nothing and smoke. It was also like returning to the apartment building where I had lived as a young child to see how tiny in actuality the courtyard was. It was like returning to the summer camp where I had spent the happiest times of my childhood to find it abandoned and all the buildings leaning over. Godard and the others in the new wave were inventing a new language of film, using all the old bones and props and body parts of ordinary, unthought-through understandings of what a man is and what a woman is.

The Christmas cactus has bloomed on the window that looks out on the road. It isn't a cactus. It isn't possible to will yourself to love anything. We love our new sheets that are gunmetal gray. I resist the social urging to feel doom. I was once at a decrepit artist residency so bleak with dirt I spent my days in the lobby of a nearby hotel, wearing headphones and using the Wi-Fi. At night I watched The Wire, unable to turn away from children entrapped in the drug world the show depicts. I kept borrowing the DVDs from the local library. When we bought the house where we live now, I didn't understand what was needed to make it right. It was like falling in love—which is more or less the rejection of feeling doom. At the artist colony, I found funny the space between feeling lucky to be there and feeling disgust at what it was. At another colony I lived amid an infestation of stinkbugs no one tried to contain. In order to work or sleep, I had to vacuum up hundreds of bugs from the furniture and walls several times a day. The thing about colonies is they are mostly uncomfortable in one way or another and you need to bring your own gunmetal gray sheets. At this one, while everyone slept, you could stream movies, and it was heaven.

Before the women’s movement, every woman used to say, “I’m strange. I’m not like other women.” I wake up early in order to live longer. When I was twenty-five, I borrowed money from a friend to pay my rent and left behind a gold bracelet as collateral. People around Andy Warhol wondered if they should be more damaged or more whole.

A man came to fix the filtration system in our house and showed me videos of himself in the Grand Canyon. He was riding a mule in snow along the narrow path that cuts back and forth like a ribbon in the wind. I once visited the Grand Canyon at sunset. The rocks were on fire, and the man I had come with said, “It looks like the last day this is ever going to happen.” In the videos, the air was gray above the icy Colorado River, and snow speckled the brown mules. The descent into the Grand Canyon takes six hours and the climb up eight hours, along a mile of stairs.

In the Before, I was walking one night in Manhattan with the man who had showed me the Grand Canyon when I tripped on the sidewalk outside a Rite-Aid. This man was now my former boyfriend, and my lip was bleeding. The store had the blue-gray air of a space station. People were poring over heart-shaped boxes of chocolates and violent computer games, pretending not to notice the blood. A young man with a thin mustache led us to the employees’ toilet down a hallway lined with soft drinks and scouring cleansers. My former boyfriend had dark, flowing hair. I had bitten my lip in two places, and the inside was visible outside, like a palm turning out. He said, “You won’t be the worst-looking person on the subway.” It was the reason he’d been a good choice for me. Before he left, I said, “I want to hold your hand.” He took my hand, sticky with blood, and kissed it.

All the trees have dropped their leaves, and the branches are jumping in the wind. For women, the past has no information. In 1968, the house of famous modernist and anti-Semite Louis-Ferdinand Céline burned down, destroying manuscripts, furniture, and mementos. His parrot Toto remained safe in an adjacent aviary. In the 1990s, I found myself friends with a number of people who’d been junkies. By the time I was born, there was a television in the house. I watched it from a couch splashed with red dahlias. To eat clams from the shell, my father would throw back his head. As the youngest child, I didn’t imagine living an adult life. I could have taken the same fall at twenty.

Laurie Stone is an author, critic, and frequent contributor to the Women’s Review of Books.