Red Rock Baby Candy By Shira Spector

Interview by Tahneer Oksman

The process was improvisational, related to quilt-making … as a mom and a person with a day job, I had to make it in a way that I could put it down and pick it up again, like sewing.

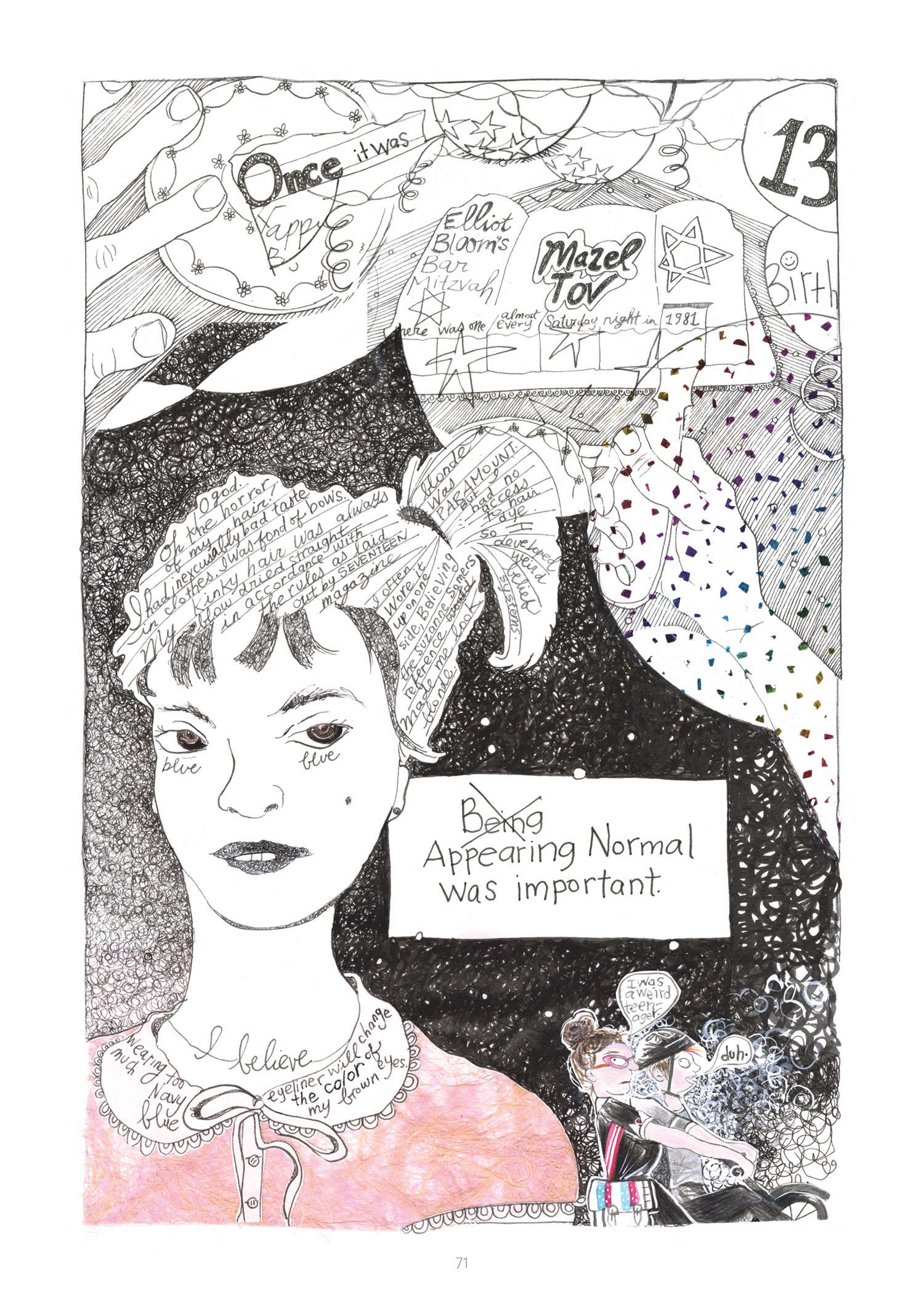

Shira Spector’s visual memoir, Red Rock Baby Candy, is a sight to behold. The hardcover volume, coming in at about eight-by-twelve inches, consists of pages packed with bold, bright colors, pencil sketches, collages, torn diary pages, inlaid photographs, and narrative text jotted and drawn in an assortment of ways, including lots of intimate pencil doodles interlaced throughout. This is a book bursting with surprises. Each spread, from its coloring to its sometimes gritty, sometimes delicate textures and its overarching configuration and design, is an unexpected delight.

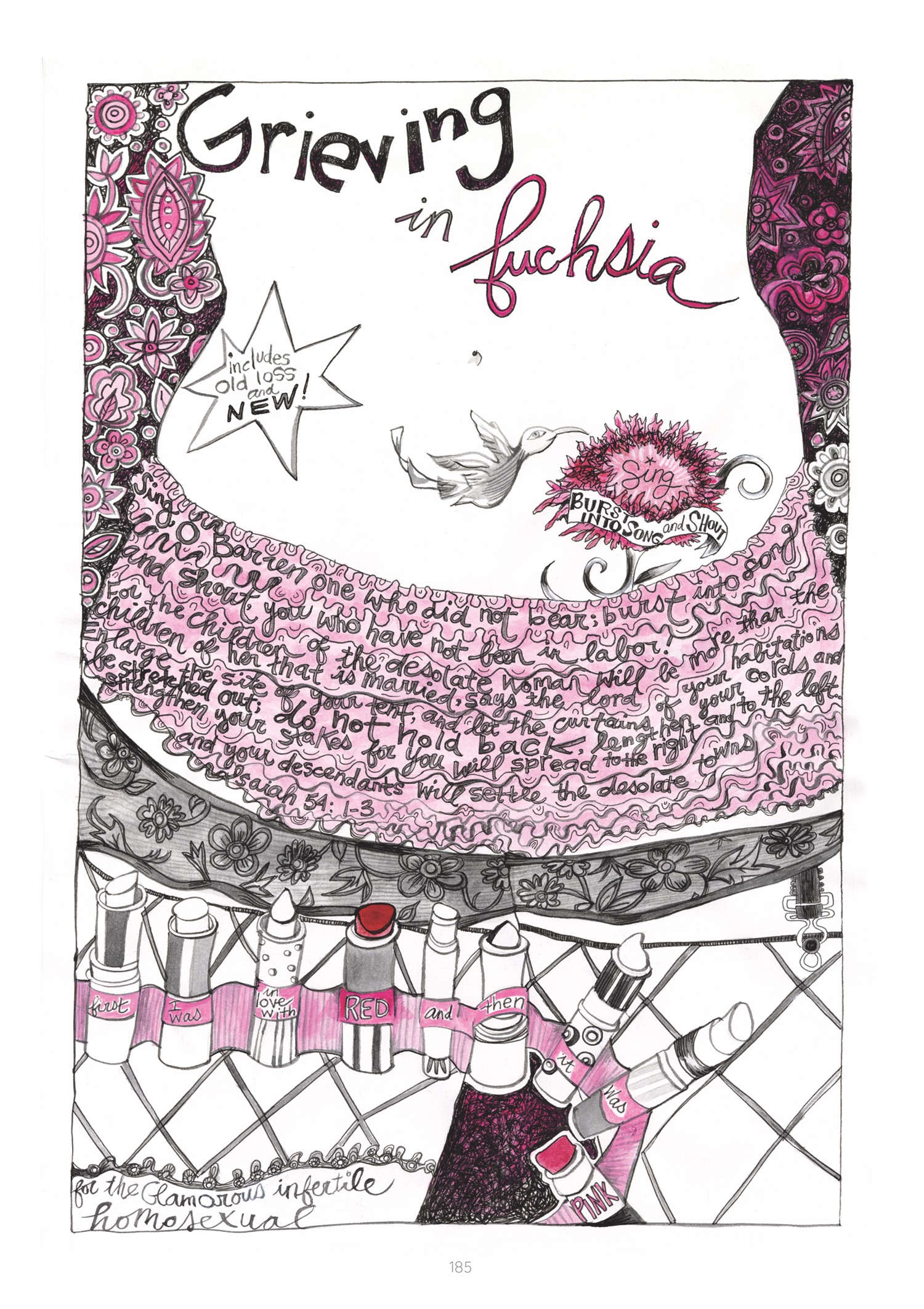

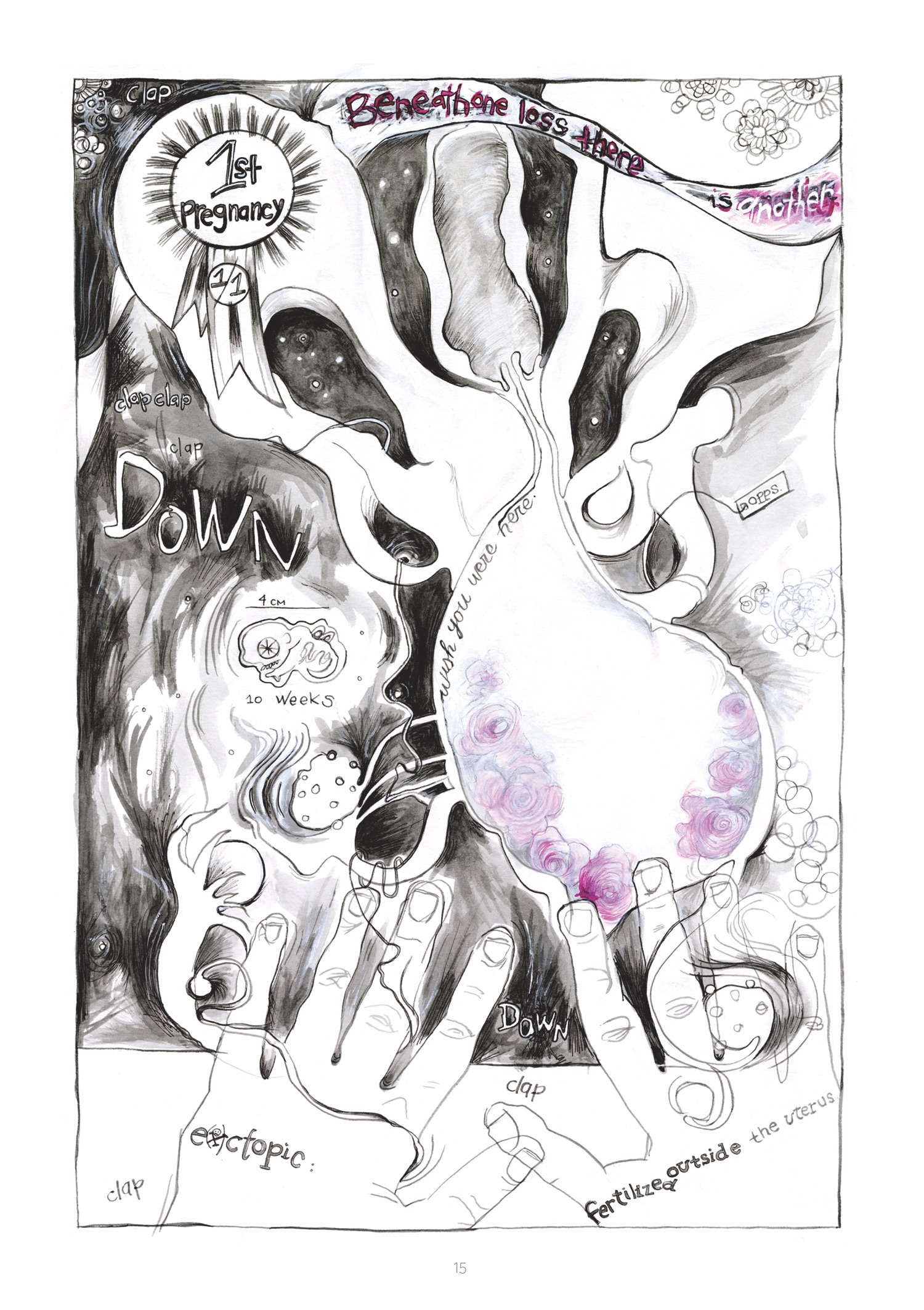

Like lots of feminist graphic memoirs, the text is hard to classify. Shira’s alter ego takes us on many journeys. Some of these take place in the “present” (the book spans over ten years in its making), and they include experiences of grieving a beloved father, infertility and pregnancy loss, and navigating the ins-and-outs of co-parenting as an artist. In the folds of these stories is a bildungsroman, in which our narrator revisits the long road that led to her proud emergence as a high-femme dyke drama queen.

Red Rock Baby Candy is a book to read for its absorbing storylines and delicate, poetic prose. It’s also one I’ll undoubtedly return to, repeatedly, in order to re-absorb and re-savor its sensual, glamorous art. Shira and I spoke one afternoon in January over Zoom, and despite the hundreds of miles between Toronto and Brooklyn, we had much to discuss: books and art and motherhood and girlhood and, not least, the complicated trajectories of radicalized and rebellious would-be Nice Jewish Girls.

WRB: How, and when, did you first start making comics?

SS: I’ve been drawing my whole life. I went to art school in the 1990s to study painting and drawing. But it was a conservative program, and I was interested in comics, and they weren’t, and they really discouraged the work I was doing.

So I basically dropped out of art school, but I kept one class, which was my fibers class. That department had a much more contemporary feel, with more mixed media and a lot of women speaking about marginalized artwork. I had a teacher, Régine Mainberger, a mentor who was a Holocaust survivor and a staunch Jewish feminist. I was exploring queer Jewish identity in my fiber work, and she really encouraged that. Other teachers wouldn’t interface with my work because I was talking about being a Jewish dyke.

At first, I started by working my comics onto textiles. The drawings didn’t feel real to me until I saw them on fabric. That’s where the layering comes through in my work. But eventually, once I lost access to all the equipment at school, I started treating paper like textiles. I took what I knew—reverse appliqué, surface design work, repetition, patterning—and moved it onto paper.

For me, it’s incredible to be working in comics, a medium that is so—I want to say, bisexual [laughs]. It’s interdisciplinary; it’s words and images, so that’s already mixed media in a sense.

WRB: Your memoir winds in so many directions, but it’s framed by grief. It opens as you lament the loss of your father and soon turns to infertility and pregnancy loss. Do you think of this book as a work of grief?

WRB: Your memoir winds in so many directions, but it’s framed by grief. It opens as you lament the loss of your father and soon turns to infertility and pregnancy loss. Do you think of this book as a work of grief?

SS: Yes and no. I started this book because I had all this grief, and I didn’t know where to put it. So I turned to my art.

The book became a house I lived in—a place that was sacred, and a place I could go and be with my grief. As you know, this culture has no room for grieving. But it’s not only a book about grief. As much as I was mapping that terrain, in the space of grieving I also found gratitude and joy. Grief is multicolored and multilayered. I wanted to bring that sensibility to this book, all of my tools. Like the deliciousness of looking at a children’s book, a picture book: where you can look at an image and look at it again, and you can just keep coming back to it.

WRB: One thing your book captures powerfully is how each experience of grief is linked up with many others. Can you talk about how you found a shape to contain all of those threads?

SS: When I was writing the book, a big question was, what is the story? I knew I wanted to talk about infertility, pregnancy loss, and the intersections I saw between those experiences and my dad’s terminal cancer and death. I think of it like setting gems into pieces of jewelry. I had those key stories, those gems.

But because it took me so long to write the book—eleven years—I ended up also weaving in everything that was happening in my life at the time. Part of that was actively parenting—being in that privileged position of being infertile and experiencing pregnancy loss, but also having a baby. It was complicated to be at that intersection.

As I wrote, the baby grew up to be a teenager. That baby had a sexuality and a gender identity of their own. Watching my son express that and come out to us really brought back my own youth, my own coming of age, my own coming out, and my own grappling with gender identity.

The process was improvisational, related to quilt-making. Not only because I come from a textile background, but also because, as a mom and a person with a day job, I had to make it in a way that I could put it down and pick it up again, like sewing.

WRB: I love that idea of the work reflecting, in its very arrangement, the circumstances in which you were creating it. Would you talk a bit more about your process? Do you tend to start by thinking first of words, or of images, or is it something more complicated?

SS: My process starts with words. The text comes to me first, and then I tear it apart. I go through this complex editing process where I pare it down. It’s like sculpting. There’s syncopation—comics are music. So sometimes one sentence will stretch out over several pages, and other times it’s a big block of text.

But even though the text comes first, and then I have images I want to use, there are times where the images assert themselves. I had very clear visions in my head of what I wanted to do, but I also really had to be listening for what the work wanted me to do and what the story demanded.

For example, there’s one image of me with my bubbie [from Yiddish for grandmother] early on. She’s drawn as just this giant stomach, and I’m hugging her. At first, I had a very definitive idea of what I was drawing, and it didn’t include her. But as I was drawing, she would show up, and then I’d erase her. And she’d show up again, and I’d erase her again. By the third time, I was like, okay, bubbie, clearly there’s a reason for this, come on in. And then this whole new stream emerged, about my bubbie and her death.

It was a scary thing to do, to let the image through; it’s a process of consenting to go deeper. I had to surrender to what the story was telling me.

WRB: Over the last fifteen years or so, there seem to be more publications trickling out, slowly, in terms of stories and art pieces related to pregnancy loss and infertility. In comics, for example, you have works by Diane Noomin, Paula Knight, Emily Steinberg, Phoebe Potts, and Anna Brewer. Could you talk about how you see your book in relation to what’s already out there?

SS: I started writing the book around 2008, when a lot of these works did not exist yet. I did get to see Diane Noomin’s short piece, “Baby Talk: A Tale of 4 Miscarriages,” at an exhibition, as well as a show of Frida Kahlo’s paintings. Both were profoundly inspiring to me.

What I found outside of that trickle was, largely, nothing. Our culture reinforces that. You’re not supposed to tell people you’re pregnant until you’re three months in because that saves everybody else from dealing with your grief if you miscarry.

I found silence except when I spoke to people one-on-one. And the more I’d speak to people, the more I’d realize how everybody had a story. Either they’d miscarried several times, or they knew someone, or their mother or their sister or their grandmother. My grandmother miscarried three or four times. I was interested in how it could be that this thing as prevalent as birth was kept so quiet.

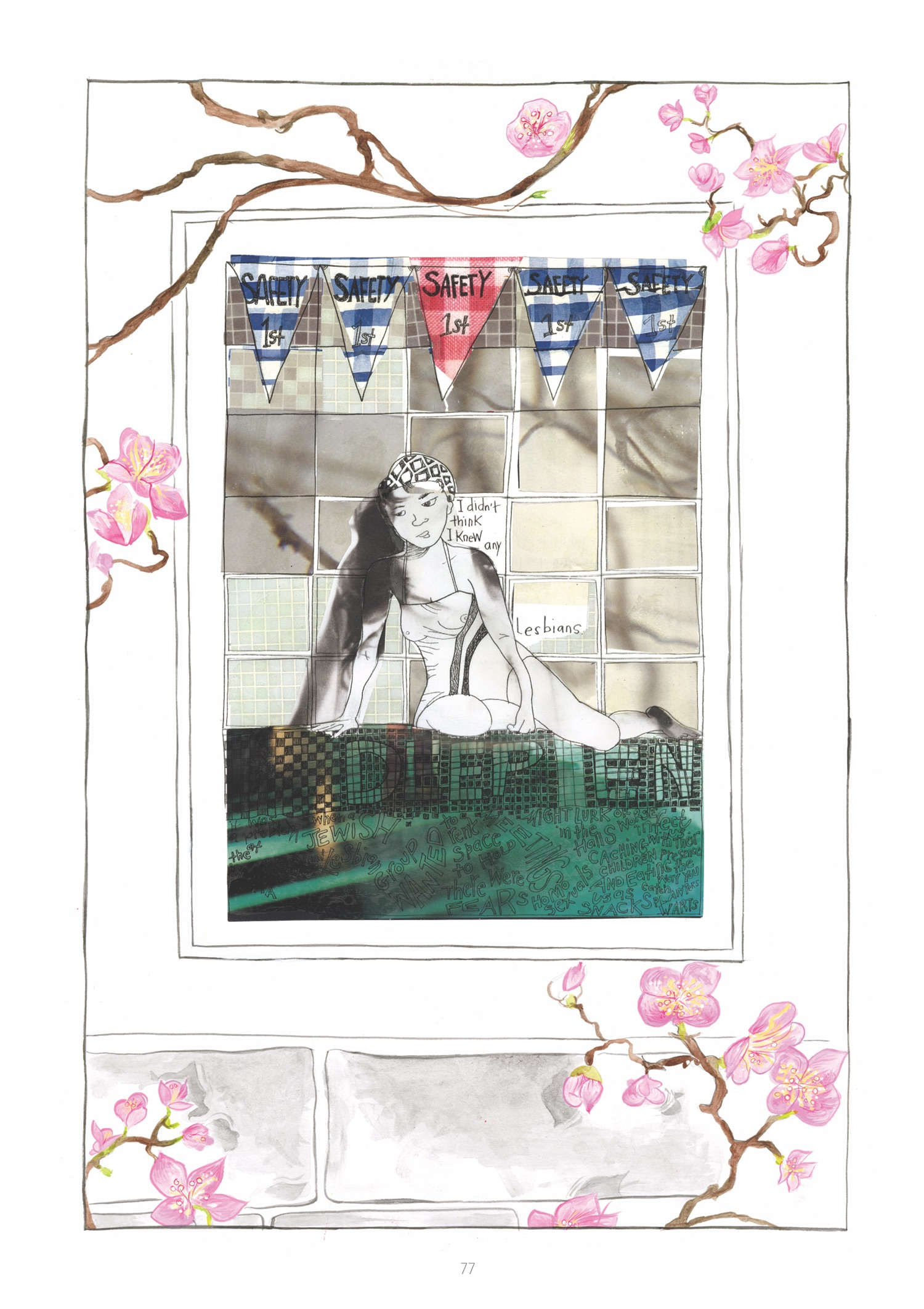

I especially wanted to talk about infertility and pregnancy loss as a lesbian because there’s a double silence when you’re queer. Historically, LGBTQ+ people have been denied the right, or the safety, to even start families. And if we do, we face violence and discrimination and the horror of having our children taken from us. Positive images exist for a reason. In the early aughts, when I was involved in the queer parenting community, there was just this overwhelming sense of shining, happy people having babies, as if to say, we may be queer but our reproductive systems are working just fine, thank you. Like no one wanted to mess up that rosy picture.

But my reproductive system was not working at all. What I found, in this community where I would expect more voices and more bravery and more communication around things people usually don’t want to talk about, was just more silence.

WRB: Though you clearly have a marked style all your own, as I was reading through your book I was reminded, in flashes, of the works of creators including Vanessa Davis, Ellen Forney, Alison Bechdel, and Aline Kominsky Crumb, among others. Could you talk a bit about influence?

SS: I love all of those artists! I grew up reading Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For, which showed me it was possible to chronicle the true lives of queer people, at a time when we had so few authentic reflections of ourselves. It was—and continues to be—a comfort and joy to read her work. I knew if there was one lesbian cartoonist, there could be more. Lynda Barry’s What It Is was another huge influence; she freed me to mix things up and tell the truth. And Phoebe Gloeckner, too. Her work is bold and visually eloquent. She gave me the courage to say what I needed to say.

In terms of painters and artists, I also love Frida Kahlo, for her daring and intimate work about her life and body. And Faith Ringgold, who passionately centers being African American and female in her work. Her story quilts were a big influence on me when I was a textile artist because they upended quilt making and are gloriously political and narrative.

Music too—Steven Sondheim, Leonard Cohen. Those artists influenced me in a way that feels incredibly Jewish. It’s a heaviness but also a playful sensibility. Sondheim has this ability to speak about three things at the same time; there are just layers and layers to his work.

WRB: Your father introduced you to musicals through Hair, right?

SS: Yes. He had music playing all the time. I think he had aspirations to be an artist himself. But he was a first-generation Canadian, and it was his job to lift the family out of poverty. His family threw everything into him becoming a lawyer, but he had such a love and reverence for the arts, and music and dance and literature, and he really nurtured that in me.

His mom worked in sweatshops, and he worked [as a labor lawyer] for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. So that’s beautiful to me, too. That he was involved with union work, and specifically that he fought back against the same system that exploited his mom. I’m very proud of him. I wish he had had another lifetime to explore that other part of himself.

WRB: In your book, you include flashbacks to your teens and adolescence, when you were attending a Jewish day school and grappling not just with influences from the culture at large (like Seventeen magazine), but also pressures from your small Jewish community. Could you talk a bit more about what that was like?

SS: I was not exactly raised to be the person I became. I mean, in some ways I was. My parents had a real social justice framework. I was taught early on that you had to stand up for what’s right and use your voice. It was your obligation. Tikkun olam [a Jewish concept, roughly translating to “repair of the world”], and all that. They were invested in us being culturally identified as Jewish.

When I think back on that time, and being in that conservative, religious school—I was with only Jewish kids, and when you were in grade seven, every weekend there was another bar mitzvah. There’s a culture around those places, and it’s pretty conventional. And I was starting to figure myself out. I was just learning that I was a creative person, and my sexuality was starting up. All the other kids seemed to be just eating it up with spoons, and I felt like, this isn’t right for me.

Going back to that time is hard. But it did inform who I became. I learned that that wasn’t my place, and then I found alternative spaces. It was a matter of rejecting the life that was handed to me—here’s how you become a Nice Jewish Girl: you go to nice Jewish schools, and maybe you’ll be a dentist, or you’ll marry a dentist, and you’ll have children, and it’ll be fine. And I was like, no. That’s not how it’s going to go.

There was a rebellion, and then I found Jewishness again. It’s almost like being a born-again Jew! [laughs]

WRB: Color figures throughout your book—especially bold reds and pinks, like fuchsia. You also talk a bit about your love of body products, like makeup and perfume, and your passion for extravagant wedding dresses and clothes. Could you talk more about the relationship between this kind of conspicuous, pronounced aesthetic, and the exploration of gender and sexuality in your book?

SS: I identify as femme and high femme, which to me just means super-femme. Femme identity is a complex thing to describe and make visible. For me, it’s about larger-than-life femininity, a construct that is available for anyone, of any gender, to play with. It’s making better use of that same femininity that was oppressing me as a young adult and was thrown at me but didn’t work for me, that unattainable Seventeen magazine femininity imposed on Phoebe Cates and Brooke Shields. It was about being demure and innocent, not in charge of yourself, which was supposed to be sexy somehow.

And it was about the color pink. I have a love-hate relationship with pink. For a while, everything in my life, from my 1968 birthyear and onwards, was pink. But I never felt like the right kind of girl. I always felt so unlike everybody else.

Pink became fuchsia for me. Fuchsia is over-the-top pink. It was about taking all those trappings—the lipstick, and the pretty stuff—and weaponizing it. Making it not about men and boys at all. Making it about me and other women, and taking pleasure in my body on my own terms. Just being able to say, yes, I love sex, I love pleasure.

The senses for me are what make everything worthwhile. The bees in my story—there’s one on the cover—are about that: they pull me back to a kind of fertility that isn’t about reproduction. Which is similar to a kind of femininity that isn’t about the patriarchy, which, for me, is femme.

WRB: Your child and your partner, the models for the characters in the book named Max and Chris, respectively, are figured in spurts. Did you find it difficult to navigate your explorations without invading their privacy? And how did you find parenting while being an artist influenced your work?

SS: Both are generous to allow me to take their sort of likeness—I strive, actually, for essence—and turn them into characters that are them but not them.

When Max was little, he would crawl into my lap sometimes and draw with me. There are a lot of his drawings integrated into the book, and sometimes his writing, too. You can’t always do that. But when I could make room for him to be part of it, I did. When kids are little, it’s easier to talk about them and your experiences of parenting and not feel like you’re giving anything away. The line is clearer. But it gets more complicated as they get older. There’s a part of the book where I’m starting to think about my own adolescence, and I ask Max [then a teenager] about the people in his life, who’s dating whom, and Max is like, you’re not gonna know these stories, they’re not your stories. It was at that moment that I drew a line; I started to be more careful.

I wanted Max’s transition to be part of the book because it was part of what was happening, and I’m proud of him and thrilled for him. But I wouldn’t dare speak for him. It’s a concern when you’re writing your life—whose story belongs to whom.

My wife, the Chris character, she’s been so generous with me. We had discussions before I even started the book, and I said, you need to tell me if there’s anything you find wrong with this. Because my relationship with the two of them means more to me than anything else.

Tahneer Oksman is Associate Professor of Academic Writing at Marymount Manhattan College, the author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs (Columbia University Press, 2016), and the co-editor of the anthology, The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell: A Place Inside Yourself (University Press of Mississippi, 2019). She often reviews graphic novels and illustrated works for the Women’s Review of Books.