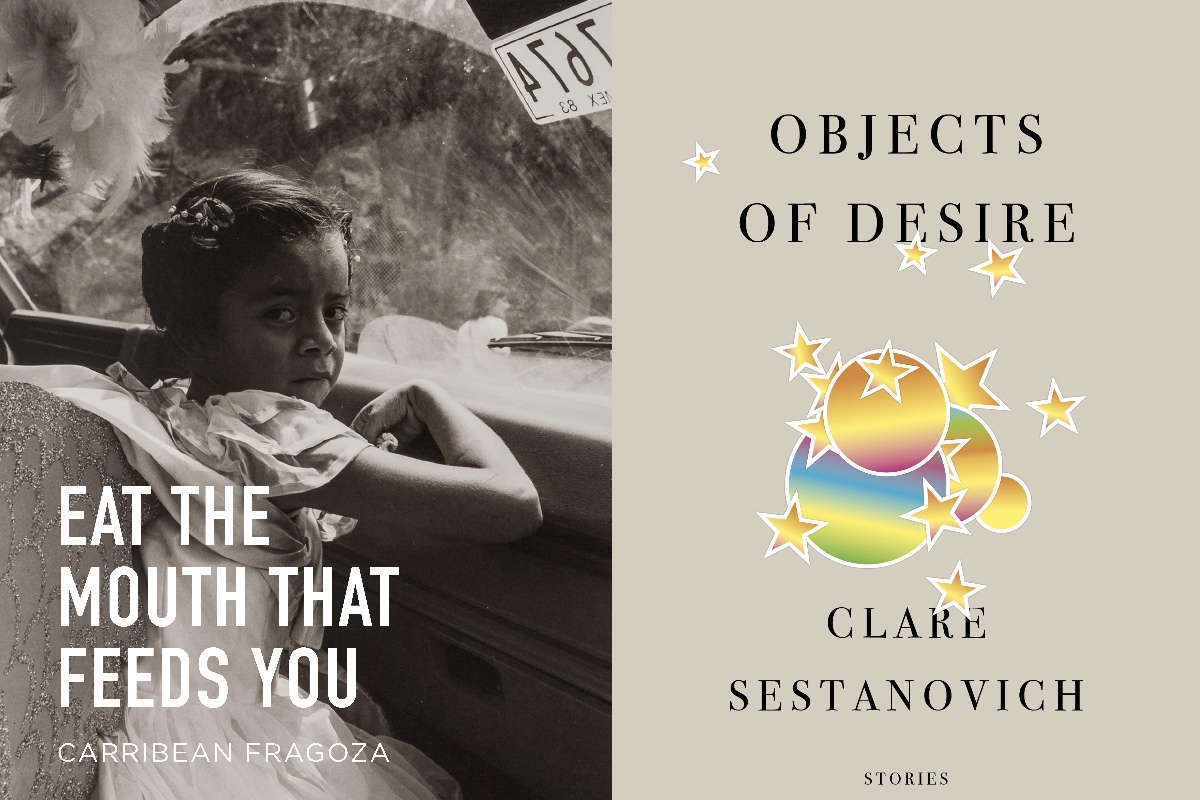

Objects of Desire By Clare Sestanovich;

Eat the Mouth That Feeds You By Carribean Fragoza

Reviewed by Anjanette Delgado

Both collections make clear that the antagonist of a woman’s story is the patriarchal world in which she lives, and that she must outsmart and defeat that antagonist in order to complete her hero’s journey.

My firstborn made her entry into the world forty-four days before I turned twenty, when I was a sophomore in college, and certain beyond measure I did not want a relationship with her father. My life then: attend college wearing handed-down muumuus in lieu of the maternity clothes I could not afford. Wobble across campus while ignoring the pitying looks as much as the jeering ones, which included those from my Theory of Communications professor. Evenings, stand for the earth’s longest full-time shift while inserting flyers and shopper specials into next day’s newspaper. Walk to bus stops and wait for slow-moving, noisy, fuming buses in a city with alarming rates of gender violence. Live far below the poverty line. Who chooses to have a baby under those conditions? I don’t know. It’s entirely possible I was stupid when I made the worst decision I’ve never regretted. All I knew was I wanted that baby, desperate for a reason to fight, for a person of my own to love.

My firstborn made her entry into the world forty-four days before I turned twenty, when I was a sophomore in college, and certain beyond measure I did not want a relationship with her father. My life then: attend college wearing handed-down muumuus in lieu of the maternity clothes I could not afford. Wobble across campus while ignoring the pitying looks as much as the jeering ones, which included those from my Theory of Communications professor. Evenings, stand for the earth’s longest full-time shift while inserting flyers and shopper specials into next day’s newspaper. Walk to bus stops and wait for slow-moving, noisy, fuming buses in a city with alarming rates of gender violence. Live far below the poverty line. Who chooses to have a baby under those conditions? I don’t know. It’s entirely possible I was stupid when I made the worst decision I’ve never regretted. All I knew was I wanted that baby, desperate for a reason to fight, for a person of my own to love.

Some years later, I had an epiphany about those years. I realized that what I had needed, and had not known where to find when nineteen and faced with impending clueless motherhood, was a catalogue of women’s lives. Or more precisely, a list of choices for women, with examples of women living those lives, making those choices. A What Color Is Your Parachute?, but for my life.

Instead, I had fiction. My mother read novels and short stories, so that was where I learned my “life lessons.” Rare though it was, in short stories, a woman could make an unlikely, maybe even scandalous choice, and it would turn out well for her. A collection of those kinds of stories might have reflected me back to me. At the least, it would have kept me company, validated me, been a friend.

Of course, now that I am no longer so desperate for that catalogue, it appears in the form of not one but two short story collections, each differing wildly from the other in style, viewpoint, language, and place. Both collections document women’s possible paths, showing the results each one might yield in worlds that, real or imagined, read as if remembered. Both collections also make clear that the antagonist of a woman’s story is the patriarchal world in which she lives, and that she must outsmart and defeat that antagonist in order to complete her hero’s journey.

First, in Objects of Desire, Clare Sestanovich presents us with the probing, almost clinical, X-ray of the modern urban professional (or would-be professional) female, each story feeling like a different layer or life stage of the same woman. A woman we know. Maybe a woman we are.

Here she is in the opening story, “Annunciation”:

By the time she meets Ben, Iris has had a lot of sex. Some of it is good and some of it is bad, and she has taught herself not to care too much about the difference. In general, not caring requires studiousness. She gives herself assignments: eat peanut butter straight from the jar; steal ChapStick from CVS. She has dropped acid and skipped class and let a boy lick circles around her asshole. There are dozens of tubes of ChapStick in her sock drawer now, and sometimes she takes them out just to look.

See? Choices. Some absurd, others pointing unflinchingly at the heartbreak of women’s lives lived in perennial missing of something, all that time wasted in figuring out how to be, counterintuitively walking in one direction to achieve the goal that waits at the opposite end because a straight line is “just not done,” as in this passage from the title story, in which the protagonist, though she finds it undesirable, accepts living with her partner’s cat, a relic from “a private and intense time in his life,” which in retrospect has “become, in its way, a sacred time. Leonora does not believe in this sacredness, but she understands why it’s useful to Jon and takes care not to violate it. To become truly happy, she tells one of her friends, is to betray the unhappy person you used to be. The friend disagrees. No, the friend says, it is to liberate that person.”

Notice the false hypothesis, the settling, the self-shrinking of Leonora in order to fit Jon’s premade cupboard. Notice the unmasking of the premise that we are liberated. So often our decisions turn out to be traps constructed by what we have been hypnotized to want, a cause-and-effect scenario that repeats endlessly: expectations, (false) choices, frustration, guilt born of the path ultimately taken.

Reading these stories by Sestanovich, you remember all your important choices, which she presents to you along with their necessary context because you are a woman and have probably pushed it aside in real life, the better to flog yourself without.

For example, in “By Design,” Suzanne looks back on a life that was anything but, bitterly regrets allowing the opinions and expectations of others to limit her in ways big and small, as in when “her mother said, You can’t take an infant camping.” Ultimately, thanks to context Sestanovich builds in, she realizes that the “opinions” she heeded were not really optional but more doled out like law, narrow and unforgiving, so that she would have had to be a different person living in a different time to reject them.

In “Terms of Agreement,” too, the protagonist finally tells him she wants “to be loved in spite of: my mood swings and my neck pain, my secret arrogance and my secret laziness,” later clearly seeing the trap set up by her partner, and how it forced the breakup that resulted only after she’d made clear what she needed.

And this may be why these stories—as well written and enjoyable as they are to delve into and deconstruct—do leave a bit of a retro aftertaste, proof of where we still are despite all the years of our fight. The book is, then, a record of the nuanced moments that condition and rule our lives. These are known barriers, restated, like enjoying a brilliant episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and then feeling sad that it is just as relevant today as when it first aired.

By contrast, Eat the Mouth That Feeds You, by Carribean Fragoza, tastes like resistance; she’s fucking fed-up with fighting:

I don’t know which is worse, my mother pacing around in the house like a caged parrot or the Ladies waiting for me like a car full of clown buzzards. I often think about escaping both, running into the shadows of the neighbors’ yards, hurdling over fences from one lawn to another until … well, I don’t know what. That’s part of the problem, I guess. I wouldn’t know what I’d be running toward. I rush to the curb and leap into the Ladies’ packed Honda before anyone can see. I make sure to slump low in the backseat before we peel away with a screech like we’re a pile of witches in a hurry. Every time, I start out by convincing myself it might not be so bad. Lately, I have to try harder.

You hear it, right? Defiance, but also decisions that, in Fragoza’s lush and dreamy fabulist fiction, might just be what turns out to be most real. Not the pottery you can eat to remember your youth in one of the stories, or the lion that somehow knows who the winners of TV talent contests are. Those are magical icing on Fragoza’s narrative cake. What feels real here are the stakes embedded into each tale. The unfathomable choices that every woman in these pages faces: Loving a child who destroys you. Leaving your country. Killing your love for a partner who doesn’t honor you. But mostly speaking up, protesting, asking for basic things at work, standing up to an abuser. Simple things that carry great risk when you are a woman. That is the cold “real” that coexists with the magical in this story collection and gives it its beautiful sense of urgency. That last quoted passage is from the story “The Vicious Ladies,” a speeding-in-reverse revenge-porn romp showing the benefits (solidarity, power) and the risks (overzealousness, distrust born of fear) of living in a world run by women when their control is continually under threat. Meanwhile, “Lumberjack Mom,” shows an abandoned woman take a weapon to her heartbreak and rattle the roots of all her living things:

We found our mother chopping through a tangle of branches. Her arms were gashed by the long thorns, as if they’d been fighting back for their lives. Her face was also covered in a web of thin scratches, but they were hardly visible against her darkly tanned face. The scratches were lined with tiny beads of black blood that shone like unblinking eyes in the sun. The lime tree, our little lime tree. We were aghast. She had chopped it down. She chopped our lime tree down to brambles. She slashed off all of the leafy branches without regard for the countless white blossoms, heavy with pollen and bees.

Wonderful anger is everywhere in this collection, leads to decisions that sound impossible, but that these female characters make anyway.

Then there’s the title story: a mother watches in terror as her toddler devours her family roots, literally: “I saw my daughter swallow the photograph, her own lips learning to sharpen into that scythe. When she ate my grandmother’s photograph, my daughter looked at me bewildered.”

Amid the fantastical image of a child who figuratively eats her origins, literally cannibalizing everything her mother loves—her own body, the last remaining images of ancestors—is a suspicion, even for this child, that something is being kept from them. They sense there are options out there called “fantasy” because women have been tricked into believing they are not possible. But they are.

In the end, as fiction and as that catalogue for life I wanted, Objects of Desire and Eat the Mouth That Feeds You are both excellent, gorgeously written studies of choices made. What differs are the stakes. Sestanovich’s protagonists have first-world lives and the privilege of their obsessions. They can analyze mistakes, go back to work tomorrow, have a drink with friends after, see the therapist weekly, work it out. Meanwhile, though it might comfort Fragoza’s women to enjoy an afternoon on the couch considering the roads not taken, they can’t. They are too angry, too worried, these ladies. Too much shit continues to go down, and now they will eat your stupid photo, burn down your damn lime tree, and if people call them vicious or unseemly? So what? Like they haven’t been called that before?

Anjanette Delgado is the editor of Home in Florida: Latinx Writers and the Literature of Uprootedness (University of Florida Press, 2021). In addition to being the author of two novels, her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Pleiades, Vogue, The New York Times “Modern Love” column, The Hong Kong Review, and on NPR.