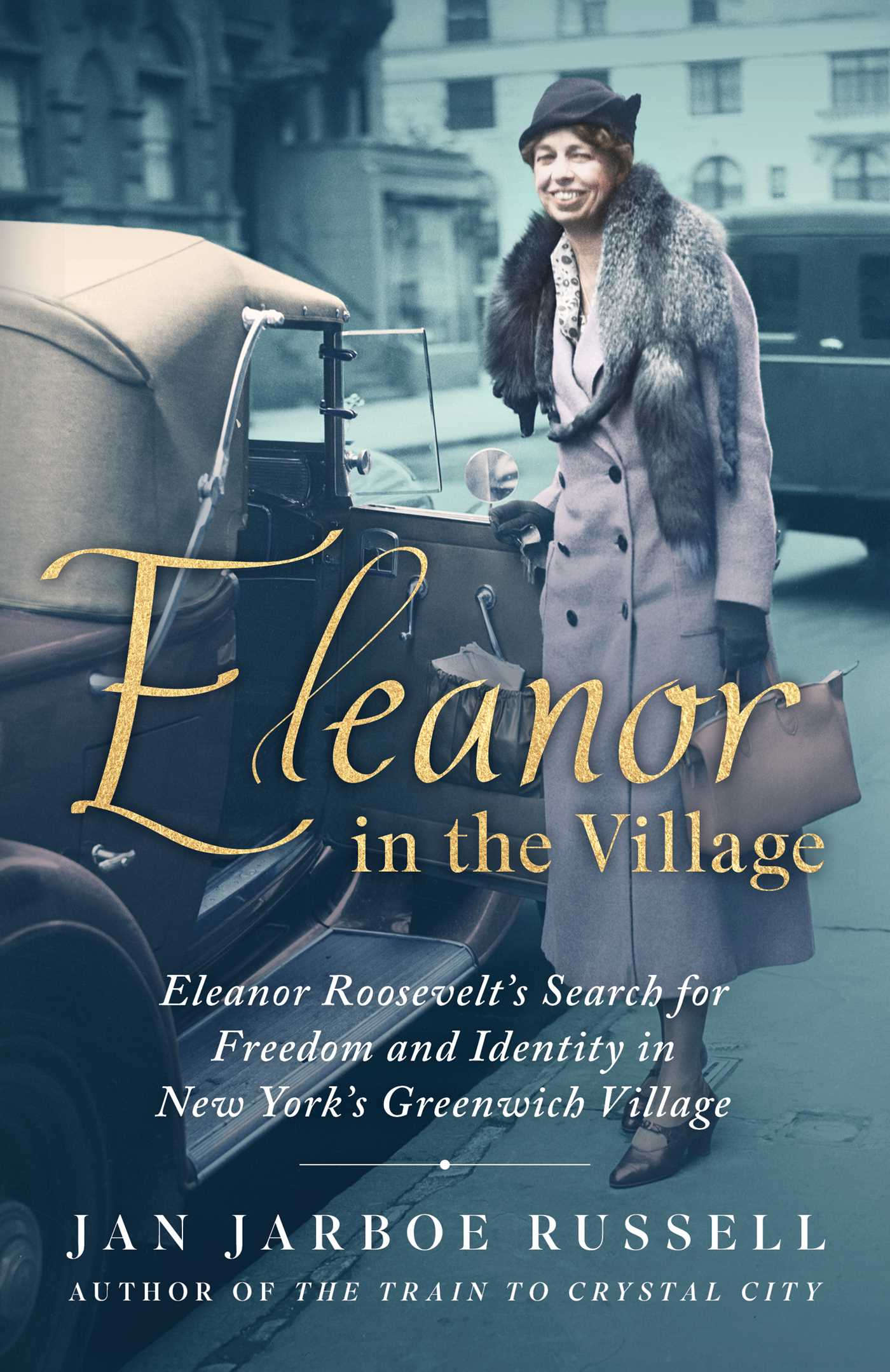

Eleanor in the Village: Eleanor Roosevelt’s Search for Freedom and Identity in New York’s Greenwich Village By Jan Jarboe Russell

Reviewed by Sarah Schulman

The Eleanor Roosevelt of Jan Jarboe Russell’s bumpy yet engrossing book is a person who decides who she must be and then wills herself to get there. When her husband, Franklin, is struck suddenly by polio, she takes a hard look at their six children and the labor of building his future political career. “I would have to become a good deal more companionable and more of an all-round person than I had ever been before.” And so she does. Born on New York’s West 37th Street in 1884, Eleanor’s life was one of constant change. At the center of the nation’s ruling elite, she faced every obstacle by aligning with the poor and refugees, seeking just solutions with, and for, the exploited of the world.

The Eleanor Roosevelt of Jan Jarboe Russell’s bumpy yet engrossing book is a person who decides who she must be and then wills herself to get there. When her husband, Franklin, is struck suddenly by polio, she takes a hard look at their six children and the labor of building his future political career. “I would have to become a good deal more companionable and more of an all-round person than I had ever been before.” And so she does. Born on New York’s West 37th Street in 1884, Eleanor’s life was one of constant change. At the center of the nation’s ruling elite, she faced every obstacle by aligning with the poor and refugees, seeking just solutions with, and for, the exploited of the world.

Eleanor’s hard-drinking father and self-involved mother left her under a nanny’s care, and French was her first language for this reason. By the age of eight, her mother and brother had died of diphtheria, and her father, a dissolute alcoholic, died two years later by jumping out his apartment window. By age ten, the orphaned Eleanor was living with her grandmother. Her first biographer, Joseph Lash, saw this experience as key to her future commitments. “Desertion of the young and defenseless,” he wrote, “remained an ever-present theme.”

Eleanor was educated at a private girls’ school located in one of the Vanderbilt mansions. Then her “independent” aunt arranged for her to study in France with Marie Souvestre, an atheist, lesbian intellectual. The teacher’s love affair with a student was the subject of the 1949 lesbian novel, Olivia, in which Eleanor appears as a supporting character. Education at Souvestre's school included discussions of women’s suffrage, socialism, and the useless folly of war. But when Eleanor’s grandmother learned that she was allowed to explore cities unchaperoned, she brought her home. There, surrounded by alcoholics, Eleanor reportedly lived with three locks on her door to protect her from her uncles.

A man she met at her own debutante ball introduced her to Ellen “Bay” Emmet, an artist whose studio in Greenwich Village brought Eleanor below Fourteenth Street. What Jarboe Russell makes especially clear is Eleanor’s comfort with lesbians and bohemians, in sharp contrast to her class and the high society from which she was profoundly alienated. So, Eleanor started going “Downtown” into bohemia, even before she ran into Franklin Delano Roosevelt, her fifth cousin, on a train where they talked for three hours. Once engaged, the couple took different routes through society. Franklin went to Harvard Law School; Eleanor started working at the Rivington Street Settlement on the Lower East Side, where she taught dance and calisthenics to Jewish and Italian girls working in factories and doing piecework. She took public transportation to work and walked through the Bowery each day.

Eleanor Roosevelt's residence at 29 Washington Square West. Photo courtesy of New York University Archives.One day, Franklin picked up Eleanor from work, and she asked him to help take a sick girl home. Witnessing the horrible conditions inside the tenements that day, FDR has his first encounter with poverty. It is here that Jarboe Russell misses an opportunity to draw out the implicit connection between Eleanor’s values and FDR’s future political contributions. Her formative experiences with lesbians, artists, and members of the working class provided his first exposures to progressive and inclusive politics. As FDR’s affair with Lucy Mercer advanced, and Eleanor’s life became more emotionally autonomous, Jarboe Russell sketches in Eleanor’s subsequent forty-year relationship with the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, and the values the Downtown neighborhoods reflected.

Eleanor Roosevelt's residence at 29 Washington Square West. Photo courtesy of New York University Archives.One day, Franklin picked up Eleanor from work, and she asked him to help take a sick girl home. Witnessing the horrible conditions inside the tenements that day, FDR has his first encounter with poverty. It is here that Jarboe Russell misses an opportunity to draw out the implicit connection between Eleanor’s values and FDR’s future political contributions. Her formative experiences with lesbians, artists, and members of the working class provided his first exposures to progressive and inclusive politics. As FDR’s affair with Lucy Mercer advanced, and Eleanor’s life became more emotionally autonomous, Jarboe Russell sketches in Eleanor’s subsequent forty-year relationship with the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, and the values the Downtown neighborhoods reflected.

In 1921, Eleanor became best friends with a couple, Esther Everett Lape and Elisabeth Fisher Read, who lived in the Village at 20 East 11th Street. The three helped each other develop their understandings of children’s rights, unions, and women’s sexual autonomy, and Lape was one of the first advocates for national healthcare in the US. In the 1930s Eleanor rented a pied-à-terre in their building. She also became friends with a second lesbian couple, Marion Dickerman and Nancy Cooke, who lived at 171 West 12th, and whom FDR called “she-males.”

When FDR restarted his political career post-polio, Eleanor famously became his “eyes and legs,” going where he couldn’t go and meeting people he couldn’t meet. Her hands-on experience of Depression-era America again formed the basis of his evolving social vision. The more she saw of people’s real lives, the more radical she became, and the greater was her influence on his New Deal recovery policies.

What Jarboe Russell makes especially clear is Eleanor’s comfort with lesbians and bohemians, in sharp contrast to her class and the high society from which she was profoundly alienated.

There are a lot of holes in Jarboe Russell’s storytelling, and her claim gets abstracted. She writes that “Eleanor’s unorthodox activities in Greenwich Village did not go unnoticed by J. Edgar Hoover.” But even a small excavation reveals that the FBI was motivated to start spying on Eleanor because of her support of the League of Nations, not her life on East 11th Street. Hoover’s file on her grew to 3,900 pages, mostly focused on her alliances with internationalists and one-world ideals. Her interest in class, gender, race, and national equity was what bothered Hoover. Jarboe Russell’s thesis is that these radical commitments were grounded in Eleanor’s relationships with the Village, but the author’s own evidence really argues that it was her lifelong intellectual, political, and personal compatibility with lesbians that radicalized her. That some of these lesbian allies lived in the Village seems incidental.

The book makes a few glaring errors, like calling Café Society’s owner, Barney Josephson, Barney Josephine. And Jarboe Russell ruminates on Hoover’s obsession with Eleanor’s sexuality without citing concrete examples. There is also a lot of frustrating filler, like speculating about what score Eleanor would have received had she ever taken the Myers-Briggs personality matrix.

Eleanor with Lorena Hickok in 1933. Photo courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.In 1942, in the middle of FDR’s third term, Franklin and Eleanor signed a four-year lease on a fifteenth-floor penthouse at 29 Washington Square West with a sprawling view of the neighborhood, overlooking the park. It had a wheelchair-accessible lobby for the disabled president, though he never spent the night there. After his death in 1945, Eleanor’s lover Lorena Hickok moved to the Roosevelt estate in Hyde Park, where she lived until her death in 1968. Eleanor, however, ended her life on the Upper East Side, living with a Jewish heterosexual couple, Dr. David and Edna Gurewitsch. There she died in 1962.

Eleanor with Lorena Hickok in 1933. Photo courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.In 1942, in the middle of FDR’s third term, Franklin and Eleanor signed a four-year lease on a fifteenth-floor penthouse at 29 Washington Square West with a sprawling view of the neighborhood, overlooking the park. It had a wheelchair-accessible lobby for the disabled president, though he never spent the night there. After his death in 1945, Eleanor’s lover Lorena Hickok moved to the Roosevelt estate in Hyde Park, where she lived until her death in 1968. Eleanor, however, ended her life on the Upper East Side, living with a Jewish heterosexual couple, Dr. David and Edna Gurewitsch. There she died in 1962.

This is a thin book with a sketchy premise that does not prove its claim, yet its fascinating subject surpasses the work’s limitations and provides a stimulating read.

Sarah Schulman’s most recent book is Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP, New York 1987–1993.