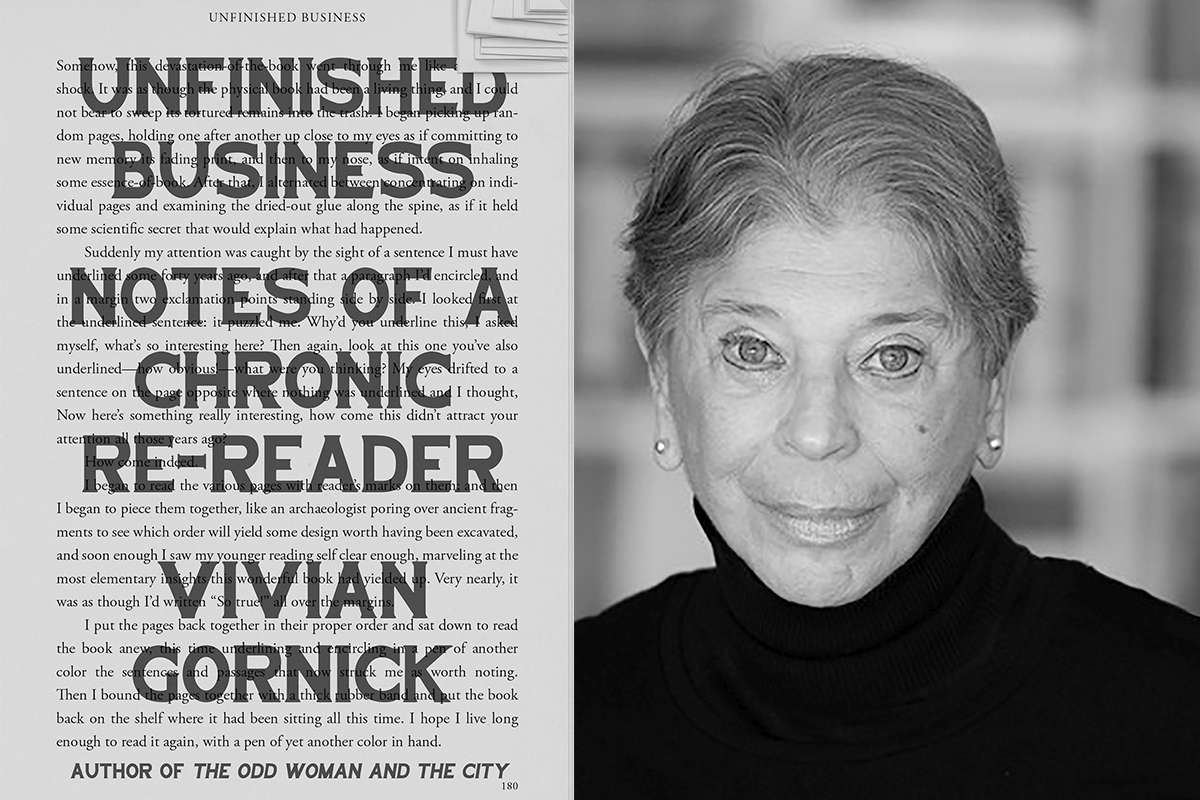

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-reader By Vivian Gornick

Reviewed by Laurie Stone

Vivian Gornick doesn’t care what you think about this book. She doesn’t care what you think about anything. She loves without apology, and love reduces her to jelly on the floor. There are no faked orgasms here about shoulds.

Vivian Gornick doesn’t care what you think about this book. She doesn’t care what you think about anything. She loves without apology, and love reduces her to jelly on the floor. There are no faked orgasms here about shoulds.

All her creativity comes from not caring, and out of that freedom has tumbled what she needs to turn over a thought. As if a thought is three dimensional, like a chair hung in space you can rotate and cantilever. What would the thought look like if I flipped the conclusion to its opposite? Is that the thought I was too afraid to form? As if a thought is a character in action, and you can launch it back in time and reconstruct the house where it pressed its ear to the floorboards, listening to adults behaving inscrutably.

The thoughts in Unfinished Business are about books Gornick returns to because she likes to reread. This is not a guide for how to be. The books that draw her are madeleines, summoning the self she was at previous readings. Criticism in Gornick’s hands is a sneaky form of autobiography—a series of love letters to moments she was jolted into consciousness. Sneaky and enlivening because the narrator looks out at something other than itself, and in that looking reveals a self to the reader.

The books Gornick returns to are Eurocentric. From the Before rather than the Pause or the Now or the Next. Mainly white people. Mainly women. Some working class, as was Gornick growing up. Among them D.H. Lawrence, Colette, Hardy, Duras, Delmore Schwartz, Natalia Ginzburg, Doris Lessing, and Elizabeth Bowen. There are some stunning examples of literary analysis along the way, Gornick slipping under the skin of the authors she admires and trying to sense events as they do.

Here she writes about Sons and Lovers: “This habit of Lawrence’s, of making the character suffer two and even three reversals of judgment in the space of a single paragraph ... not only signifies the routine instability of one’s actual moods, it nails the torment at the heart of any decision rooted in mixed emotions, and the second—no, not the second, the third—time I read the book it hit me hard.”

The great thing about Gornick’s book is where a passage like this darts next—back to her life. Such a tactic runs the risk of sounding like one of those tedious accounts people chime in with on social media posts. Gornick’s jumpcuts, however, are richly entertaining. Also, they dramatize the way we become known to ourselves through reading. She writes: “I was now old enough to have experienced many times over the alarming bewilderment of my own erratic behavior—the morning of my first wedding day I was nearly hit by a truck because, as I crossed the street, I was still saying yes, no, yes, no to myself, and failed to stop walking when the light turned red—and I could feel viscerally the shock of Lawrence’s acuity in tracing the staccato nature of emotional confusion.”

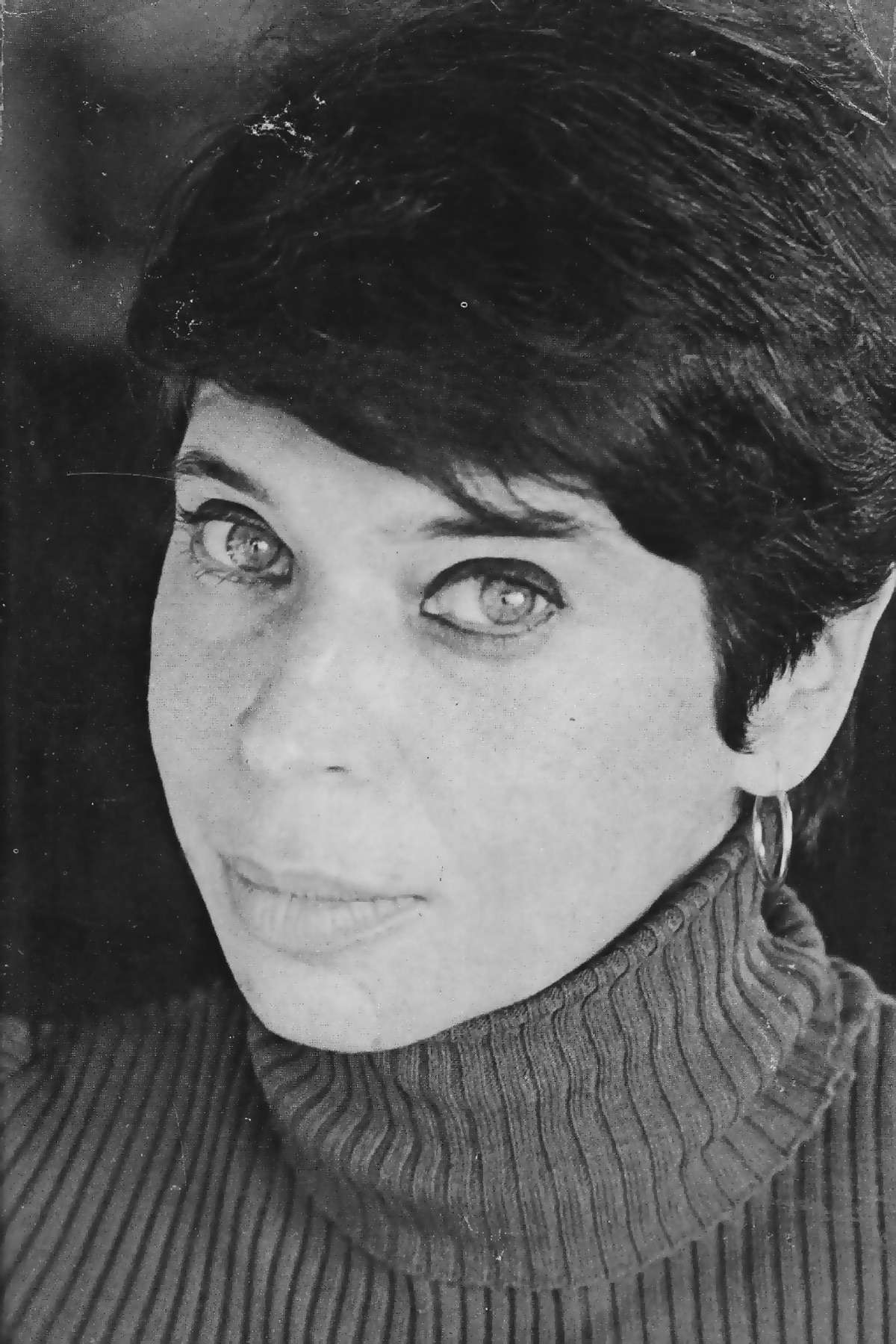

Gornick in 1977Gornick reminds the reader of times they, too, read books to learn how to live. For years in the 1960s and 1970s, I read books with orange spines by women. Virago and Penguin editions. Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, and Colette at a clip, the Margarets Drabble and Atwood, Violette Leduc, Jean Rhys, Gayl Jones, Plath, Sexton.... What books made you?

Gornick in 1977Gornick reminds the reader of times they, too, read books to learn how to live. For years in the 1960s and 1970s, I read books with orange spines by women. Virago and Penguin editions. Virginia Woolf, Doris Lessing, and Colette at a clip, the Margarets Drabble and Atwood, Violette Leduc, Jean Rhys, Gayl Jones, Plath, Sexton.... What books made you?

Not only are we made by books, the thickness of our experience in turn stirs our insights into them, as Gornick brilliantly illustrates along the way. About Duras’s The Lover, she writes, “What the girl learns during this affair is not only that she is a catalyst for desire but that she herself is aroused by her own powers of arousal.” Writing about Bowen’s 1948 novel The Heat of the Day, written during WWII, Gornick nails the author’s “great subject”: “The acclimatization to deadened feeling—in war or in peace ... this is the enemy of life, the criminal charge she brings against the human condition: that which allows us to adapt ourselves to the atrophied heart. Herein lies the inborn tragedy of this, our one and only life.”

Arousal and deadened feeling are two hot spots for Gornick in whatever she reads, and by revealing the private nature of these themes to us, she enlarges her authority to speak about them. Back and forth, back and forth she goes, from remembering how she read something in the past and why she read it that way, to her present sense of both the past reading and her take du jour. In early chapters she seems to be looking for a “best” or “truest” interpretation of a text. She started life as a utopian, in search of an idealized Large Life. For her parents the key had been Communism. For Gornick it was feminism, until she saw that idealism—with its rightthink and groupthink strategies—made life smaller and less free than experience was teaching her.

As the chapters unfold, the delight Gornick takes is in the provisional nature of any reading, and her prose takes flight, growing more cunning and imaginative. In the third chapter, like the fulcrum of a seesaw, she tells a startling and crazy story that is so narratively right for her book, she would have needed to invent it if it hadn’t happened.

She’s illustrating something or nothing. It doesn’t matter. Suddenly she recalls being eight and desperately looking forward to a party. She gets into a fight with her mother, who, in revenge, cuts the dress where the child’s heart would be. “‘You’re killing me,’ she always howled, eyes squeezed shut, fists clenched, when I disobeyed her or demanded an explanation she couldn’t supply or nagged for something she wasn’t going to give me. ‘Any minute now I’ll be dead on the floor,’ she screamed that day, ‘you’re so heartless.’”

In later years, starting when she is eighteen—again at thirty and forty-eight—she asks her mother how she could have done such a thing to a child, and each time, flatly, her mother responds, “That never happened.” With each denial, Gornick’s scorn expands until, one day in her late fifties, she reports: “On a cold spring afternoon ... on my way to see her, I stepped off the Twenty-Third Street crosstown bus in New York, and as my foot hit the pavement I realized that whatever it was that had happened that day more than half a century ago it wasn’t at all as I remembered it. “Migod, I thought, palm clapped to forehead, it’s as though I was born to manufacture my own grievance. But why? And hold onto it for dear life. Again, why? When my hand came away from my forehead, I said to myself, So old and still with so little information.”

The comedy and joy of being wrong—so you can write like this and have a story to tell that goes nowhere as it burrows into our own dead hearts—that’s what Gornick lives for, and why we need her.

Laurie Stone is a regular contributor to the Women’s Review of Books. She is author most recently of Everything is Personal, Notes on Now, which features several essays that originally appeared in the WRB. In a New Yorker review, Masha Gessen noted the book’s reframing of “the personal is political” to describe “our current predicament—everything that is not personal has vanished” and praised how Stone “suggests a way of thinking sharply, imaginatively, beautifully, from right here.”