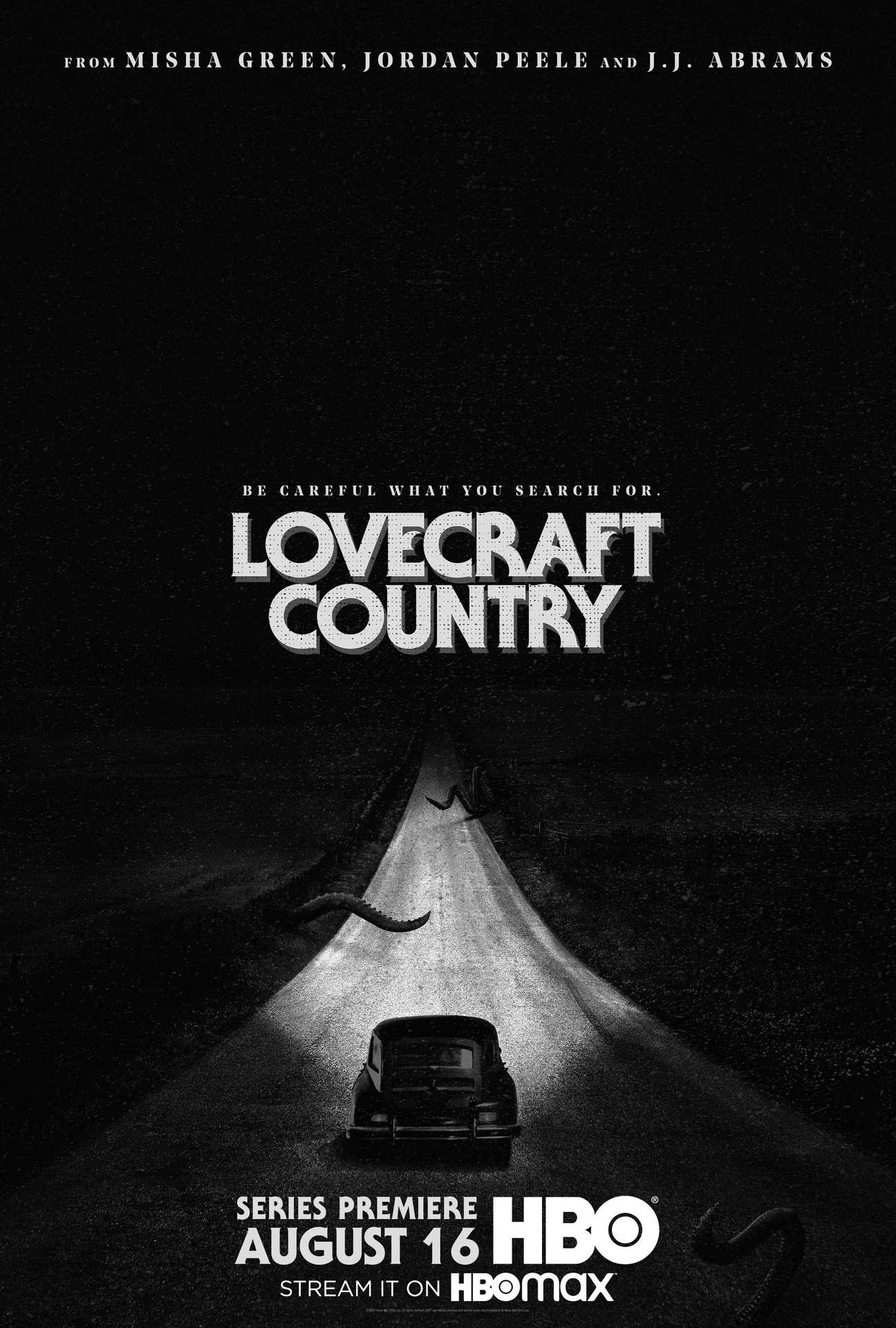

Lovecraft Country Adapted by Marsha Green from a novel by Matt Ruff

HBO, 2020, 10 episodes

Reviewed by Kovie Biakolo

After all the real-life surrealism the world has faced this year, 2020 desperately needed some magic. Magic is what the HBO series Lovecraft Country certainly attempts, and with it, a multitude of myths, history lessons, poetry, and puzzles, making for an engrossing if perplexing viewing experience. Set in the 1950s, the show begins with the protagonist Atticus “Tic” Freeman (Jonathan Majors), a Black American Korean War veteran traveling from Florida to his hometown, Chicago, in search of his father, Montrose (Michael K. Williams), after receiving a strange letter. Accompanying him on this perilous journey are his uncle, George (Courtney B. Vance), and a childhood friend later turned romantic beloved, Leti (Jurnee Smollett).

After all the real-life surrealism the world has faced this year, 2020 desperately needed some magic. Magic is what the HBO series Lovecraft Country certainly attempts, and with it, a multitude of myths, history lessons, poetry, and puzzles, making for an engrossing if perplexing viewing experience. Set in the 1950s, the show begins with the protagonist Atticus “Tic” Freeman (Jonathan Majors), a Black American Korean War veteran traveling from Florida to his hometown, Chicago, in search of his father, Montrose (Michael K. Williams), after receiving a strange letter. Accompanying him on this perilous journey are his uncle, George (Courtney B. Vance), and a childhood friend later turned romantic beloved, Leti (Jurnee Smollett).

The trio soon discover they have more to be afraid of than the potent racial terrors they come across as they travel the segregated country through “sundown towns”—white municipalities in which Black people’s presence can result in death, the danger exponentially increasing in some places, after the sun sets. Although it’s clear that the backdrop of racism is in itself a kind of monster, there are literal monsters too, including petrifying, flesh-eating creatures, not to mention peculiar white people who let the Black travelers indulge in some reprieve at a strange manor, Ardham Lodge, where even stranger occurrences and rituals take place. Soon, the viewer learns that Tic is the last living direct descendant of Ardham Lodge’s founder, Titus Braithwaite, who also established the secret society (or cult), Sons of Adam. The superficial mission of the group is immortality via the biblical garden of Eden, though the deeper purpose is, predictably, power—and Tic is at the center of how to attain it.

If this brief synopsis brings confusion, you’re not alone. Lovecraft, a horror drama that employs the idiosyncrasies of dark fantasy and science fiction, is hardly a straightforward watch. The series, which was developed and written by Marsha Green (Underground), is partially the revision, disruption, and subversion of its titular author, H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937), whose style and work instituted an eponymous genre in his posthumous celebrity: Lovecraftian horror. As a writer, Lovecraft was as brilliant as he was unapologetically racist and xenophobic, even by the standards of his day. Green’s effort is therefore undoubtedly a feat of reinterpretation, even where it falters and befuddles. Perhaps the most apt description of the show comes from New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow, who tweeted, “It’s like reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved for the first time: it’s so beautifully rendered but nearly impossible to follow."

Lovecraft does indeed borrow from Morrison’s work, though it makes use of Paradise rather than Beloved. Richly allusive, the show deploys the prose and profundity of other great American writers and artists of the twentieth century, including Octavia Butler’s gripping Bloodchild and Other Stories, James Baldwin’s unforgettable 1965 “The American Dream and the American Negro” speech, and Gil Scott-Heron’s momentous spoken word poem “Whitey on the Moon.” Above all, the show is Green’s rendition of author Matt Ruff’s 2016 novel of the same title, which juxtaposes the Jim Crow-era United States against the cosmic horror genre and its originator, H.P. Lovecraft.

If Lovecraft's intention was for its supporting characters to be contingent on Tic's narrative—which is doubtful, given how the stories of its many characters are told—it hasn’t exactly failed but didn’t entirely succeeded either. While Majors is exceptional in his portrayal as Atticus, so much of the character as written has yet to create an urgent interest in the viewer. In contrast to this lack of clarity or deficiency of excitement plaguing its protagonist, Lovecraft’s depiction of women is complicated, curious, and compelling. Leticia “Leti” Lewis could have been portrayed as a mere sidekick to Tic, a friend who becomes a romantic partner in the quest to uncover the truths about the Sons of Adam. Yet Green’s construction of Leti and Smollett’s portrayal of her—as brave and beautiful, quick-witted and quick-on-her-feet—do not allow for the character to be lost in the details of the lead. It is often Leti’s actions that are critical to the show’s intensity, whether she is escaping their first encounter with monsters, purchasing a house for Black people in a white neighborhood, or steering Tic’s focus and temperament in their explorations.

Mosaku (left) and Smollett (right) steal the show as Ruby and Leti, half-sisters whose relationship is complicated by colorism. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOWe know little about Leti’s background other than that she has a somewhat uneasy relationship with her half-sister, Ruby (Wunmi Mosaku). Their mother is dead, though her presence is tangible in the sisters’ dialogue. It’s a subtle but noteworthy fact of Lovecraft that even when the women play minor roles or are unseen, their stories are present—a much welcome nuance on television. And Ruby’s character is even more captivating than Leti’s, perhaps accidentally so—Mosaku’s scene-stealing ability draws the viewer’s enthusiasm for the character. When we first meet her, she is emblematic of the burden of being an older sibling to a wild-child younger sister. What is unsaid is the repercussion of colorism that exists in the space between the two women, accentuating that dark-skinned Ruby needs to be more respectable than her light-skinned sister. But Ruby is transformed when she meets William (Jordan Patrick Smith), a white man with whom she has sex. Lovecraft ensures the viewer understands this kind of racial proximity as familiar: white men seeking Black women for sex in the shadows. Except William offers Ruby more than a clandestine sexual entanglement. Instead, by the power of magic, he gives her something more: access to the freedom and power of white womanhood.

Mosaku (left) and Smollett (right) steal the show as Ruby and Leti, half-sisters whose relationship is complicated by colorism. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOWe know little about Leti’s background other than that she has a somewhat uneasy relationship with her half-sister, Ruby (Wunmi Mosaku). Their mother is dead, though her presence is tangible in the sisters’ dialogue. It’s a subtle but noteworthy fact of Lovecraft that even when the women play minor roles or are unseen, their stories are present—a much welcome nuance on television. And Ruby’s character is even more captivating than Leti’s, perhaps accidentally so—Mosaku’s scene-stealing ability draws the viewer’s enthusiasm for the character. When we first meet her, she is emblematic of the burden of being an older sibling to a wild-child younger sister. What is unsaid is the repercussion of colorism that exists in the space between the two women, accentuating that dark-skinned Ruby needs to be more respectable than her light-skinned sister. But Ruby is transformed when she meets William (Jordan Patrick Smith), a white man with whom she has sex. Lovecraft ensures the viewer understands this kind of racial proximity as familiar: white men seeking Black women for sex in the shadows. Except William offers Ruby more than a clandestine sexual entanglement. Instead, by the power of magic, he gives her something more: access to the freedom and power of white womanhood.

Even with all the limitations that exist at the intersection of whiteness and womanhood, Ruby utilizes the power William gifts her primarily for material gain and obtains a high-end retail job she has had an eye on. For the first time, she experiences safety and a freedom from fear—freedom from Blackness under the white American gaze. It’s an uncomfortable, perhaps even an erroneous narrative that suggests Black people, especially Black women, would trade their skin for one that is higher on the racial hierarchy, given all the pitfalls of misogynoir. Indeed, Ruby concludes that her experience of white womanhood, despite what it affords her, is hollow; she wants some of its allowances but doesn’t actually desire it. She and William continue their sexual relationship and what appears to be a conflicting yet budding friendship, even after Ruby discovers that William is really a magical personification of Christina Braithwaite (Abbey Lee Kershaw); Titus Braithwaite is also her ancestor, and Tic, her distant cousin.

The sexual relationship between Christina/William and Ruby is worth careful contemplation, markedly in one scene, where, after Emmett Till’s funeral, Ruby begins having sex with Christina-as-William in her transfigured white body, only to turn back into herself in the climax of the act. It is, without a doubt, one of the most grotesque, fascinating sex scenes on television: Ruby’s return to her own body is always accompanied by the blood and disfigured skin and bone of the white woman she transforms into. The pair’s sexuality within the confines of their respective transformation inadvertently allows the viewer to imagine sex as an act beyond the boundaries of gender and even personhood.

Outside of the double performance as William, Christina is an enigma whose intentions are questionable from the start and become more surreptitious as the show proceeds. Smart and shrewd, she is determined in her quest to enter the garden of Eden and subsequently acquire immortality, and she uses her power over Tic to do it. But in most ways, Christina remains a mystery. At times, her character seems more ornamental than functional, her dialogue often reduced to obscure, mundane haikus. On the other hand, Kershaw’s Ruby retains an air of intrigue but renders understanding of both her privileges and constraints as a white woman—a self-awareness that bring more relief than enticement.

Jamie Chung as Ji-Ah, one of Lovecraft Country's many magical female supporting characters. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOAside from Leti, Ruby, and Christina, the show offers a number of delightful—and literally magical—minor characters. Tic’s aunt, Hippolyta (Aunjanue Ellis), who we meet as a curious but reserved woman in service to her husband, gets the opportunity to transcend space and time in a multiverse. Then, there is Ji-Ah (Jamie Chung), whose character might be deserving of a thesis study entirely. Ji-Ah, who was Tic’s beloved when he was serving in Korea, is possessed by a kumiho, a nine-tail fox spirit, a result of a shaman’s intervention in her childhood sexual abuse. The spirit is able to kill Ji-Ah’s sexual partners and access their memories. While introducing Korean folklore in a seamless way, Lovecraft both reproduces a trope of women as potentially dangerous, sexual mythical entities, and constructs an intricate figure who oscillates between gentle and deadly, human and mystical, making for a powerful display of duality in the character.

Jamie Chung as Ji-Ah, one of Lovecraft Country's many magical female supporting characters. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOAside from Leti, Ruby, and Christina, the show offers a number of delightful—and literally magical—minor characters. Tic’s aunt, Hippolyta (Aunjanue Ellis), who we meet as a curious but reserved woman in service to her husband, gets the opportunity to transcend space and time in a multiverse. Then, there is Ji-Ah (Jamie Chung), whose character might be deserving of a thesis study entirely. Ji-Ah, who was Tic’s beloved when he was serving in Korea, is possessed by a kumiho, a nine-tail fox spirit, a result of a shaman’s intervention in her childhood sexual abuse. The spirit is able to kill Ji-Ah’s sexual partners and access their memories. While introducing Korean folklore in a seamless way, Lovecraft both reproduces a trope of women as potentially dangerous, sexual mythical entities, and constructs an intricate figure who oscillates between gentle and deadly, human and mystical, making for a powerful display of duality in the character.

Smollett's Leti is no mere sidekick to Majors' Tic. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOUnlike these women whose representations are wonderfully dynamic, if not without flaws, there are two outstanding characters whose depictions floundered in imagination and effect. Tic’s dad, Montrose, is caught in a multigenerational cycle of abuse (having inflicted it on Tic as a child), and he is also gay. But in the intimate, sexual affections between him and his secret lover, Sammy (Jon Hudson Odum), their relationship is illustrated with shame as the central tenet. One could contend that this would have been a “realistic” portrayal of a romantic or sexual relationship between two men in the 1950s or even now. But a series that can conceptualize monsters and mythical creatures can surely harbor a loving relationship between the two men, devoid of shame, at least when they are present with each other. Additionally, the abrupt appearance and casually violent departure of Yahima, an Arawak Two-Spirit character, gave me pause. Arguably, brutality is part and parcel of Lovecraft, but recreating it against a gender variant person replicates that harm against those who exist outside of the gender binary and produces no consequential critique.

Smollett's Leti is no mere sidekick to Majors' Tic. Photo credit: Eli Joshua Ade HBOUnlike these women whose representations are wonderfully dynamic, if not without flaws, there are two outstanding characters whose depictions floundered in imagination and effect. Tic’s dad, Montrose, is caught in a multigenerational cycle of abuse (having inflicted it on Tic as a child), and he is also gay. But in the intimate, sexual affections between him and his secret lover, Sammy (Jon Hudson Odum), their relationship is illustrated with shame as the central tenet. One could contend that this would have been a “realistic” portrayal of a romantic or sexual relationship between two men in the 1950s or even now. But a series that can conceptualize monsters and mythical creatures can surely harbor a loving relationship between the two men, devoid of shame, at least when they are present with each other. Additionally, the abrupt appearance and casually violent departure of Yahima, an Arawak Two-Spirit character, gave me pause. Arguably, brutality is part and parcel of Lovecraft, but recreating it against a gender variant person replicates that harm against those who exist outside of the gender binary and produces no consequential critique.

In the final analysis, however, Lovecraft is a tremendous effort as an acutely complicated TV series. It doesn’t always succeed in fully exploring the immense depths of the characters, revisionist history, or the magical world it has created. But any sincere appraisal of the show will necessarily find its flaws as arresting as its pleasures. And where the women characters are concerned, Lovecraft bewitches.

Photo credit: Elizabeth Morris HBO

Photo credit: Elizabeth Morris HBO

Kovie Biakolo is a writer, editor, and multiculturalism scholar specializing in culture and identity. Her master’s thesis (DePaul University, 2015) conducted a sociolinguistic analysis of how popular digital media sites discuss race. Her critical analysis and reporting on race, nationality, and pop culture have been featured in The Atlantic, Essence Magazine, and Slate, among many other venues. Originally from Nigeria, by way of many places, she currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.