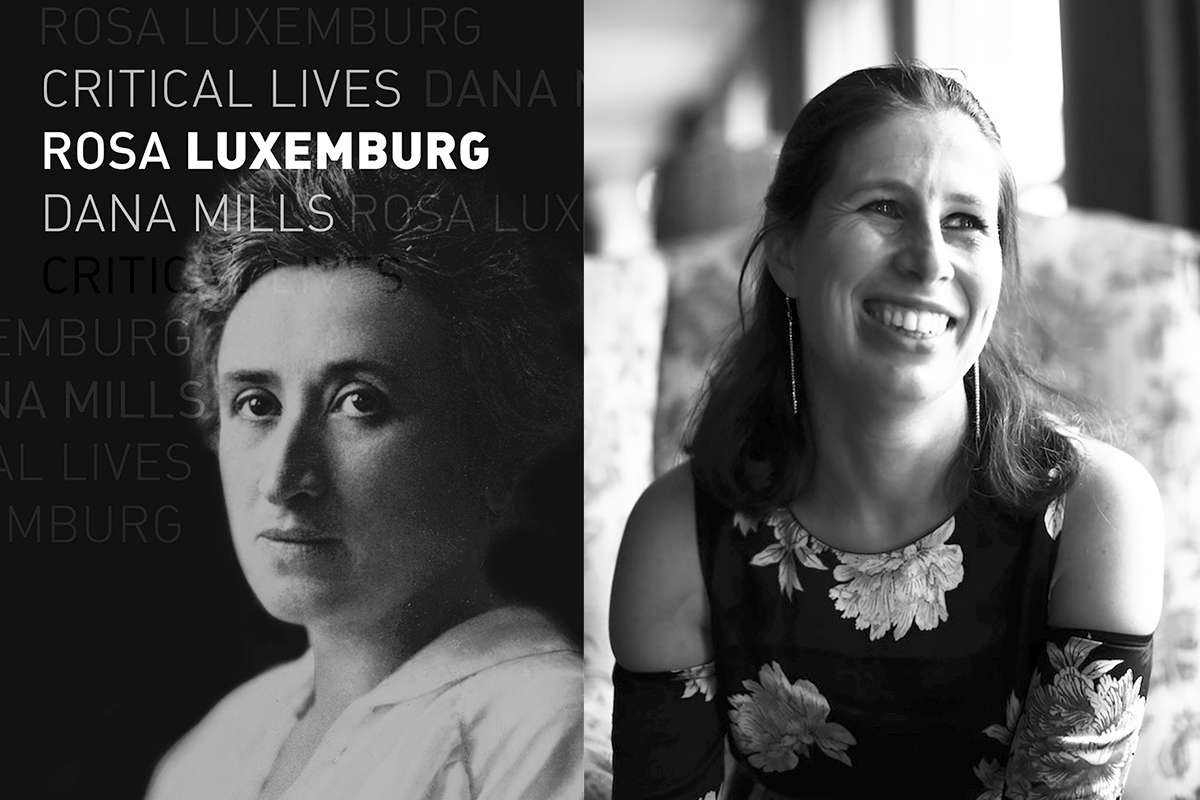

Rosa Luxemburg By Dana Mills

Reviewed by Charis Caputo

When Rosa Luxemburg was thirteen, she wrote a poem to mark the visit of German Emperor William I to her hometown of Warsaw. The year was 1884, and William, under the direction of his chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, had overseen the unification of the German state, the institution of the Anti-Socialist laws, and, most recently, the emergence of Germany as a major imperialist player in the so-called Scramble for Africa. In her poem, the budding radical Rosa confronts the emperor: “Just one thing I want to say to you, dear William. / Tell your wily fox Bismarck / ... not to disgrace the pants of peace.” Ever irreverent toward authority and convention, young Rosa was already beginning to articulate the ideals that would define her career as one of the greatest and most controversial socialists of her time: anti-imperialism, anti-nationalism, and a fearless resolve to enact justice. Twenty years later, Luxemburg was imprisoned for insulting a different German Emperor (William’s grandson Wilhelm II) and “inciting the masses” while agitating in favor of a general strike. This was only one of several times she was imprisoned during a life lived in the thick of radical European politics and cut short at the age of forty-seven, when, in the tumultuous Berlin of 1919, Luxemburg was kidnapped, shot, and dumped into a canal by members of a proto-fascist militia.

When Rosa Luxemburg was thirteen, she wrote a poem to mark the visit of German Emperor William I to her hometown of Warsaw. The year was 1884, and William, under the direction of his chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, had overseen the unification of the German state, the institution of the Anti-Socialist laws, and, most recently, the emergence of Germany as a major imperialist player in the so-called Scramble for Africa. In her poem, the budding radical Rosa confronts the emperor: “Just one thing I want to say to you, dear William. / Tell your wily fox Bismarck / ... not to disgrace the pants of peace.” Ever irreverent toward authority and convention, young Rosa was already beginning to articulate the ideals that would define her career as one of the greatest and most controversial socialists of her time: anti-imperialism, anti-nationalism, and a fearless resolve to enact justice. Twenty years later, Luxemburg was imprisoned for insulting a different German Emperor (William’s grandson Wilhelm II) and “inciting the masses” while agitating in favor of a general strike. This was only one of several times she was imprisoned during a life lived in the thick of radical European politics and cut short at the age of forty-seven, when, in the tumultuous Berlin of 1919, Luxemburg was kidnapped, shot, and dumped into a canal by members of a proto-fascist militia.

This remarkable life is the subject of Dana Mills’s new biography, a study of Luxemburg’s personal, political, and academic writings, published as part of Reaktion Book’s Critical Lives series. Mills, an activist, theorist, and member of the Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg editorial board, tells a brisk and more or less chronological story of her subject’s life and works, placing particular emphasis on the aspects of Luxemburg’s theory and praxis which made her a highly divisive figure even among her socialist contemporaries: her strident internationalism and anti-militarism, her refusal to compartmentalize various forms of oppression, and her striking combination of brazenness and empathy. Concise analyses of Luxemburg’s major works are placed in historical and biographical context, and intimate details about her rich, contradictory, and sometimes volatile personal life are occasionally extracted from extensive correspondence to give us a fuller picture of this iconoclastic soul.

Born in 1871, Luxemburg began life as a Jewish-Polish citizen of the Russian Empire: a "threefold nationality," as she would later write. Although her family was middle-class, assimilated, and steeped in Continental culture, school-aged Rosa experienced persecution as both a Jew and an imperial subject during a time of generally escalating tensions between Jews, Poles, and Russians. She was also disabled by a childhood disease of the hip that left her with a lifelong limp. This physically small, disabled, marginalized young woman was nonetheless bold and energetic. At fifteen, she joined the Polish Proletariat Party, just after the high-profile execution of some of the party’s leaders, and two years later, escaping arrest, was smuggled in a peasant’s cart across the border to Switzerland. There she continued her activism and studied law at the University of Zurich. After receiving her doctorate in 1897, she emigrated to Berlin, then the epicenter of European socialism. Through her writing and agitation, Luxemburg rapidly established herself as a brilliant, charismatic, and divisive figure within the Socialist Worker’s Party of Germany (SPD) and the Second International.

Mills argues that Luxemburg’s cosmopolitanism and the many lenses through which she personally saw and experienced oppression—ethnicity, disability, gender, imperial subjugation—guided her toward a sort of unified theory of liberation. Her writing relies heavily on the concept of “the masses,” a more flexible term than “proletariat.” As an unwavering internationalist, one of her most controversial tenets—and one that contradicted Marx himself, as well as setting her at odds with radicals and liberals alike—was her staunch opposition to nationalist revolution and national self-determination, even in her native Poland: for Luxemburg, all forms of nationalism were bourgeois constructs, and she argued that the overthrow of capitalism, an international system, could only occur at the international level. She was similarly opposed to “bourgeois feminism.” Like her socialist-feminist friends and comrades, including Clara Zetkin and Eleanor Marx, Luxemburg “could never separate the woman question from the class question,” advocating women’s suffrage as part of universal suffrage: a necessary step toward empowerment of the working class. As well, she was an outspoken critic of anti-Semitism, as exemplified by her public critique of the Dreyfus Affair, but she opposed Jewish nationalism and viewed the persecution of Jews as part of a larger system of oppression. As she wrote in a letter toward the end of her life: “I am just as much concerned with the poor victims on the rubber plantations of Putumayo, the Blacks in Africa with whose corpses the Europeans play catch ... I have no special place in my heart for the [Jewish] ghetto. I feel at home in the entire world wherever there are clouds and birds and human tears.”

Rosa Luxemburg c. 1893 (with short hair, probably self cut)Although Mills critiques the way that Luxemburg’s zealous anti-nationalism undermined her stated anti-imperialism, she also praises Luxemburg as a pioneer of what we might today call “intersectionality.”

Rosa Luxemburg c. 1893 (with short hair, probably self cut)Although Mills critiques the way that Luxemburg’s zealous anti-nationalism undermined her stated anti-imperialism, she also praises Luxemburg as a pioneer of what we might today call “intersectionality.”

In Mills’s account, Luxemburg was a proto-environmentalist. Her personal writings from prison include meditations on wasps and trees, a lament for the abused buffalo forced to carry heaps of bloody soldiers’ clothing into the prison to be washed by inmates, an injured pigeon she bathed and cared for in her cell. Some previous biographies have attended to these more “sentimental” aspects of Luxemburg, and Mills notes a kind of dichotomy in the literature: “For some, she was a romantic lover of nature; for others an unwaveringly ruthless revolutionary.” But for Mills, Luxemburg’s love of nature was not so much sentimental as an expression of her radical, universal empathy.

Elsewhere, Mills touches lightly but significantly on Luxemburg’s unconventional personal life, unafraid to confront the contradictions she finds there. Although she married a friend’s family member to receive German citizenship in 1897, she divorced shortly thereafter and was engaged throughout her life in romantic relationships with several male collaborators. Despite her radical values, she longed for an essentially bourgeois family with her first love, Leo Jogiches, who financially supported her for many years, although they never married. Her later lovers included Konstantin Zetkin, who was fourteen years her junior and the son of her close friend Clara Zetkin. Although Luxemburg never had the child she wanted, one of the book’s more dewy-eyed details is the motherly affection she had for Mimi, an injured stray cat she adopted and named after the protagonist of Puccini’s La Bohème. Relatedly, the anti-Eurocentric, anti-bourgeois Luxemburg’s fondness for opera, as well as for Shakespeare, Chopin, Goethe, and other indicators of her bourgeois Eurocentric taste exemplify the kind of contradiction and complexity Mills’s nonetheless admiring biography strives to evoke.

Luxemburg is already the subject of countless biographies and academic studies. She has been unfairly maligned as a violent Leninst, and, on the other hand, her work has been embraced by movements as diverse as liberal feminism, anti-Apartheid activism, Israeli communism, and Palestinian liberation. Since her own times she has been recognized as one of the critical leftist polemicists of that period in which communist revolution seemed eminently possible in much of Europe. From the publication of her first book, The Industrial Development of Poland (1898), she was recognized as a brilliant intellectual in the tradition of historical materialism, though unafraid to break with Marxist orthodoxy. She engaged critically with many of the questions that still engage the left today, including evolutionary versus revolutionary socialism, arguing that democratic legal reform is a means toward an end, the end being working class revolution. She was also a charismatic speaker and teacher, rousing crowds and students with her personal conviction, brash personality, and keen mind. A student of hers at Berlin’s Trade Union School recalled: “she tapped along the walls of our knowledge and thus enabled us to hear for ourselves where and how it sounded hollow.”

Luxemburg in 1910 with close friend Clara Zetkin, founder of International Women's DayBut Mills’s account emphasizes the ways in which, despite her influence and appeal, Luxemburg was increasingly ostracized by fellow leftists. Her uncompromising internationalism alienated even her fellow revolutionaries, as did her categorical anti-imperialism and vociferous critiques of racism. In The Accumulation of Capital (1913), she characterized imperialism as the inevitable result of capitalist expansion, critiquing imperial violence toward Native Americans and Black South Africans as examples of this expansion and its consequences. The contemporaneous response to this book was overwhelmingly negative: the right wing of the SPD supported colonial intervention, and even leftists found the critique of racism hard to swallow; Lenin—with whom Luxemburg had a long, sometimes close, often contentious relationship—called “the description of the tortures of Negroes ... noisy, colorful and meaningless. Above all it is ‘non-Marxist.’”

Luxemburg in 1910 with close friend Clara Zetkin, founder of International Women's DayBut Mills’s account emphasizes the ways in which, despite her influence and appeal, Luxemburg was increasingly ostracized by fellow leftists. Her uncompromising internationalism alienated even her fellow revolutionaries, as did her categorical anti-imperialism and vociferous critiques of racism. In The Accumulation of Capital (1913), she characterized imperialism as the inevitable result of capitalist expansion, critiquing imperial violence toward Native Americans and Black South Africans as examples of this expansion and its consequences. The contemporaneous response to this book was overwhelmingly negative: the right wing of the SPD supported colonial intervention, and even leftists found the critique of racism hard to swallow; Lenin—with whom Luxemburg had a long, sometimes close, often contentious relationship—called “the description of the tortures of Negroes ... noisy, colorful and meaningless. Above all it is ‘non-Marxist.’”

Sexism, of course, was also a factor in her reception. Although Luxemburg’s friendships with her female contemporaries appeared nearly unshakable, she was never accepted into the (male) inner-circle of the SPD. Her combative style aggravated misogyny. Although the SPD refused to make her an official delegate to the Second International, she showed up to her first conference with close-cropped hair and took the floor. Consequently, she suffered epithets such as “the syphilis of the Commintern” and “poisonous bitch.” She also suffered intimate abuse from her longtime partner and collaborator, Leo Jogiches, who stalked and threatened her for years after their romantic relationship fell apart. But her “insistence on ideological integrity,” writes Mills, “was part of her way to fight back against sexism.”

And that integrity, her refusal to compromise even as the SPD gained a majority in the Reichstag, and, leading up to World War I (a war which Luxemburg vehemently opposed), veered significantly to the right, resulted in her expulsion from the party and imprisonment for denouncing the German military. When she emerged from prison in November of 1918, she entered a changed world, a Germany in flux. She started a newspaper that rejected the postwar German government led by Friedrich Ebert, her former ally in the SPD. Fearing the revolutionary agitation of Luxemburg and her allies, Ebert ordered an extra-parliamentary right-wing militia to assassinate her in January 1919.

Luxemburg's was a life lived in the front seat of a volatile historical period, and it's impossible not to be compelled by it. Mills's account of this life is swift and in some ways untidy—the prose is nearly stream of consciousness at times, mingling personal tidbits and textual analysis almost at random. But as the book swept on, I was utterly transported by the drama and urgency of Luxemburg’s life, and the precarity of the world in which she lived and died.

In many ways, that world was not so different from our own, racked as we are by the abject disparities of capitalism, the ghosts of empire, the looming threat of fascist violence. A polemic, divisive, and contradictory figure, the Rosa Luxemburg with which Mills presents us is nonetheless ultimately a unifier, a whole and generous soul; her beliefs and pursuits cohered around a radical empathy and a willingness to give her life to the cause of universal justice. Regardless of how we feel about the specifics of her socialist politics, we can all take inspiration from her courage. The letter found in her handbag on the night of her assassination, addressed to lifelong friend Clara Zetkin, asserted: “One has to take history as it comes, whatever course it takes.”

Charis Caputo is editorial assistant for Women’s Review of Books and an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at NYU. She holds an MA in history from Loyola University Chicago.