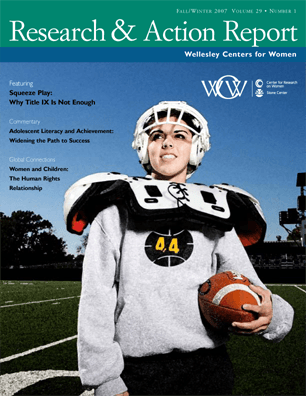

Research & Action Report Fall/Winter 2007

Q&A with Laura Pappano

Laura Pappano is the first writer-in-residence at the Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW). An experienced journalist, Laura Pappano has been widely published in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Boston Globe Magazine, Good Housekeeping, Working Mother, and The Harvard Education Letter, among other publications. While at WCW, Laura Pappano is working on a book proposal that will combine her more than 20 years writing about education with her interest in women’s issues. Her new book, co-authored with Eileen McDonagh, Playing with the boys: Why Separate is Not Equal in Sports, has just been released by Oxford University Press.

Q: What brought you to the Wellesley Centers for Women?

LP: While I was writing a weekly education column called “The Chalkboard,” for The Boston Globe, I had interviewed researchers and scholars from the Wellesley Centers for Women. I learned more about Centers’ work and I was interested in the focus on women’s experiences, the international work, and several projects that had been undertaken. I had been a visiting scholar at Radcliffe’s Murray Center for four years and appreciated that environment and the chance to be around thoughtful people doing interesting work. I met Eileen McDonagh there and we started talking about our book project. I felt WCW would be a perfect community for me to continue my research and writing.

Q: Your first book—The Connection Gap—what was its focus?

LP: The book stemmed from a Boston Globe Magazine piece that I had written, called the “Connection Gap,” which explored changes in American society that made us feel alone—even if we technically weren’t. It was really somewhat of a social commentary on the things that were making us less present, less connected. It wasn’t just about technology, but about the evolution of modern life and human relations. There are all these thousands of decisions that we make—or fail to make—without really being conscious about what will result. And in the end, you know, it profoundly changes our lives and our society.

We received such a huge response from the Magazine piece that I knew it struck a nerve and was worth exploring. I spent about five years researching aspects of social change and people’s responses to those changes, like how it affected relationships when people stopped using horses and started using cars, when the “ideal” American home went from being “efficient” in that it minimized the number of steps you had to take—all the bedrooms were close to one another and designed around a single bathroom—to houses in which privacy and separation are prized and bedrooms are built very far apart and increasingly with their own bathrooms. When you share intimate space with people, you know different things about them—even if they are in your family.

Q: So much of your current work focuses on athletics. What’s the appeal for you?

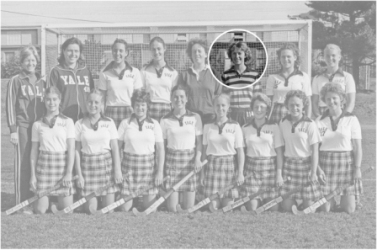

LP: I’ve always been athletic, always been interested in sports. I played Varsity field hockey at Yale, in high school my sister and I were the only girls on the town soccer team. When I was in middle school I signed up for the Danbury News-Times Carrier League baseball—I was the only girl I came across in the league at that time.

Q: What was it like breaking through barriers so early in Title IX’s history?

LP: I didn’t at first think of myself as “breaking barriers” so much as wanting to play baseball, which I’d always enjoyed. I didn’t have a lot of recreation options at the time, so when I saw a flyer attached to my bundle of newspapers at the start of the summer, it seemed perfect. Only after I’d signed up, did I realize that I wasn’t who they had in mind when they created the league. What I recall from that experience most potently was that even my own teammates didn’t want me there. I remember once I stole a base—and I knew the league rules cold. I knew that you could move on the motion of the pitcher, and yet, after I stole the base, the other team was so upset and embarrassed that even my own teammates chimed in and yelled at me to “go back, go back!” I just stood on second base and stared down at my sneakers.

Q: How old were you?

LP: I would have been 13. Earlier, when I was in sixth grade—right when Title IX was passed—the school decided that they would no longer require just girls to take home economics and only boys to take shop—we could choose which class we wanted to take. But the catch was, without ever having sampled the other course, in sixth grade you had to choose for the next two years. Clearly, in retrospect, it was meant to intimidate people into not switching across genders. But I had decided to take shop and I assumed lots of other girls were going to do that, too. The next year, in seventh grade, I found out there were only two of us in the whole school – and Heidi wasn’t in my class. When I had first turned in my sign-up sheet, my sixth grade homeroom teacher was so outraged that he led a kind of mini-campaign to try to get me to change my mind and take home economics. In front of the class he would issue graphic warnings, describing how my long hair would get caught in the machinery. I stuck with my choice, but he had rattled me. During one of the first shop classes, the teacher was standing there in his grey smock and monotone voice making that old point about measuring twice and cutting once. Well, it turns out that one of the boys cut his board the wrong length. I remember just being stunned, I can still envision standing in that shop class feeling confused because I had been told so many times that I didn’t “belong” and I had convinced myself that if anyone was going to make a mistake it would absolutely be me. To discover that a boy could make a mistake in woodshop was so freeing. It was really, really incredible. Those sorts of things made me realize that there was a lot more going on there than sports and shop.

The concerning thing is that this past spring, my daughter had a similar experience. She’s a very good athlete and she had chosen to play softball, but when we were watching her brother’s baseball team play, and she saw that some boys missed catches or didn’t follow the coach’s direction well—in essence, weren’t like mini-Major Leaguers—she turned to me and said, “I should have played Little League.” It made me realize that after these 30-plus years, there is this silent way in which we women get in line and accede to things we have no need to accede to.

Q: What did you and Eileen McDonagh want to accomplish with your new book?

LP: Sports haven’t been studied as much as other areas. The institution of sports hasn’t been viewed as a political tool or social tool, in the way that matters around workplace rules, access to education and political rights have. Sports has been treated as entertainment and recreation and hasn’t gotten the same scrutiny. In this book, we’re looking to raise consciousness around the very powerful role that sports plays in our society, particularly in enforcing a gender hierarchy in which males represent the standard and females occupy second-class status. There is a connection between the gender hierarchy enforced in athletic rules, practices, and public treatment and the maintenance of gender hierarchies in political, social, and economic arenas. In making our case, we considered legal, historical, biological, cultural, and sociological contexts. Sports are not neutral, what are the messages, the numbers, the rules, the practices, saying?

For example, why does badminton for men go to 15, and go only to 11 for women? Why are lengths of new (1996) Olympic off-road bike races designed to be 15 minutes shorter for women than for men when research has proven that women excel in endurance events? When we look at the biological differences between men and women—and we certainly acknowledge that there are biological differences—we found that the physical and physiological differences between men as a group and women as a group really didn‘t justify rule differences. There wasn’t a relationship between the sex difference and the rule differences. In fact, the rules differences just served to enforce the gender distinction: the men’s game is the standard, leaving the women’s game to still feel secondary, and in some cases, temporary.

Q: Why is that? What would say are the biggest barriers when we look at Title IX?

LP: One big issue is that when Title IX was first passed in 1972, there was this moment historically when people weren’t sure what that meant. Many schools, even colleges started integrating football teams or just allowing co-ed play. Then there were draft regulations in 1975. There was just such an extended period of time for determining what the regulations were. So the result was very unlike No Child Left Behind in which the regulations hit retroactively. Obviously, people were not eager to clarify this or implement it. When the regulations for Title IX came out, they allowed for sex segregation in contact sports. So, all of these sports that had become integrated then became separated. The act of separating contact sports in effect separated all sports. It became quid pro quo: if you have football you have field hockey. If you have gymnastics you have wrestling. There was a whole separation. The law doesn’t demand equality, it demands progress. The regulations and interpretations of those regulations allow a lot of leeway. And, it’s not particularly well enforced. Title IX’s approach of separating sports is a disservice. Separate but equal is not equal. There is a legal conflict between Title IX and the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. There is a tension between American egalitarian values and the way sports have played out under Title IX.

As far as the money, it is nowhere close to equal. Only 15 of the 326 Division I schools spend more on all women’s sports combined than they do on football. I happen to really love football, but if the NFL wants a farm league, then they should develop it. We shouldn’t be spending our equal education dollars on this. There are a lot of paternalistic attitudes toward women’s sports and even toward female athletes. Even when you look at women’s soccer—they‘re incredible athletes but there’s still that parallel of little girls in ponytails, just a bigger version than what you see on a Saturday morning on the local playing field. You can see this attitude played out in ticket prices—even when sports aren’t trying to make money. It costs $4 to see the Rutgers women’s soccer team play—but $7 to see the Rutgers men’s soccer team play. That is not about athletic department revenues; it’s about enforcing gender differences and placing different values on male and female play, regardless of how talented, interesting, or competitive the players and games may be. There’s also research that shows that when you pay different amounts for tickets, that you value the events where you paid more or made a greater investment. I would argue that if we’re going to properly enforce Title IX, that’s an aspect that must be considered.

Q: What are your concerns, most, about the future of Title IX for the playing field and the classroom?

LP: Title IX, ironically enough, was not meant to be about sports. It was meant to be about education opportunities, at a time when girls weren’t allowed to work the movie or slide projector. But, it has become most popularly debated as a vehicle for fairness in sports. The problem is that Title IX has forced all these important changes, but it’s become our own worst enemy in the sense that it codifies an inequality. I think that we need to look at it fresh—enforcing it more rigorously, being clearer about the guidelines, what it should comprise.

In terms of the classroom, I think sports need to be a nice complement to an education, not the reason that kids are in school. Sports should not take over the school or university, but in many, many cases they do. Increasingly, the best physical education programs in K-12 schools are really about life sports. The aim these days, and probably for the past 10-15 years, has been to teach kids skills that are going to promote fitness and health throughout the lifespan. And a lot more of that is done on a co-ed basis, which is a positive thing. Sports, if it’s not taken to the nutty extreme, is an incredibly, incredibly valuable experience. It provides a sense of self, of physical competence, of teamwork, of resolve and resilience. That’s very important.

Q: What do you imagine, or envision for making sports equal?

LP: Title IX came along at a moment when we could not imagine females being legitimate athletes. Today, you watch a NCAA women’s basketball game and these are just as exciting, just as competitive as when men are on the floor. The most provocative part of the argument is that we don’t have just men’s sports and women’s sports, but we need more opportunities where men and women are playing together. There are so many levels of competition and play at which we create separate male and female versions of sporting experiences. When really, let’s base it on skill. Let’s create a great model for social relations by having men and women playing together on the same field. Certainly there are stereotypes of the male athlete and the female athlete—the NFL lineman, and the petite gymnast. But if you look in any room or gathering, you find that there are more physical differences within genders than between genders. And that’s what we’re saying—sports are played by individuals and the rules shouldn’t be defined by stereotypes.

As women, we need to attend sports, we need to follow sports, we need to own teams. We need to play. We need to coach at all levels. We need to create more opportunities for co-ed sports, and for women to do non-traditional sports female don’t typically play and for boys to do sports males don’t typically play. We need to mix it up! We need to not make sports a site of rigid gender identification, because it has become a powerful gender-coding entity in our society. We need to create more comparable playing times, support venues, publicity, ticket prices. I think we need to do all of those things.

We should all be sports enthusiasts if we know what’s good for us as feminists.

Just off the Press!

Playing With the Boys: Why Separate is Not Equal in Sports

Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano

*Price: $28.00

From small-town life to the national stage, from the boardroom to Capitol Hill, athletic contests help define what we mean in America by success. And by keeping women from playing with the boys on the grounds that they are inherently inferior to men, society relegates them to second-class status in American life.

In this forcefully argued book, Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano show in vivid detail how women have been unfairly excluded from participating in sports on an equal footing with men. Using dozens of colorful examples from the world of contemporary American athletics—girls and women trying to break through in high school football, ice hockey, wrestling, and baseball, to name just a few—the authors show that sex differences are not sufficient to warrant exclusion in most sports, that success usually entails more than brute strength, and that the special rules for women in many sports do not simply reflect the "differences" between the sexes, but actively create and reinforce them. For instance, if women's bodies give them a physiological advantage in endurance sports like the ultra-marathon and distance swimming, why do so many Olympic events—from swimming to skiing to running to bike racing—have shorter races for women than men? Likewise, why are women's singles games in badminton limited to 11 points while men's singles go to 15? Surely female badminton players can endure four more points. Such rules merely reinforce a "difference" for social—not competitive—purposes.

An original and provocative argument to level the athletic playing field, Playing with the Boys issues a clarion call for sex-sensible policies in sports as another important step toward the equality of men and women in our society.

*Please note that price does not include shipping and handling. This book may be purchased from the WCW publications office by calling 781.283.2510 or by visiting www.wcwonline.org/publications.